Will Polish Economy stop or slow down due to low demographic grow? Not likely if good policies are kept: the history of a policy success. An analysis by Tangi Hetet, B.F.G. Fabrègue and Paul Sapriel.

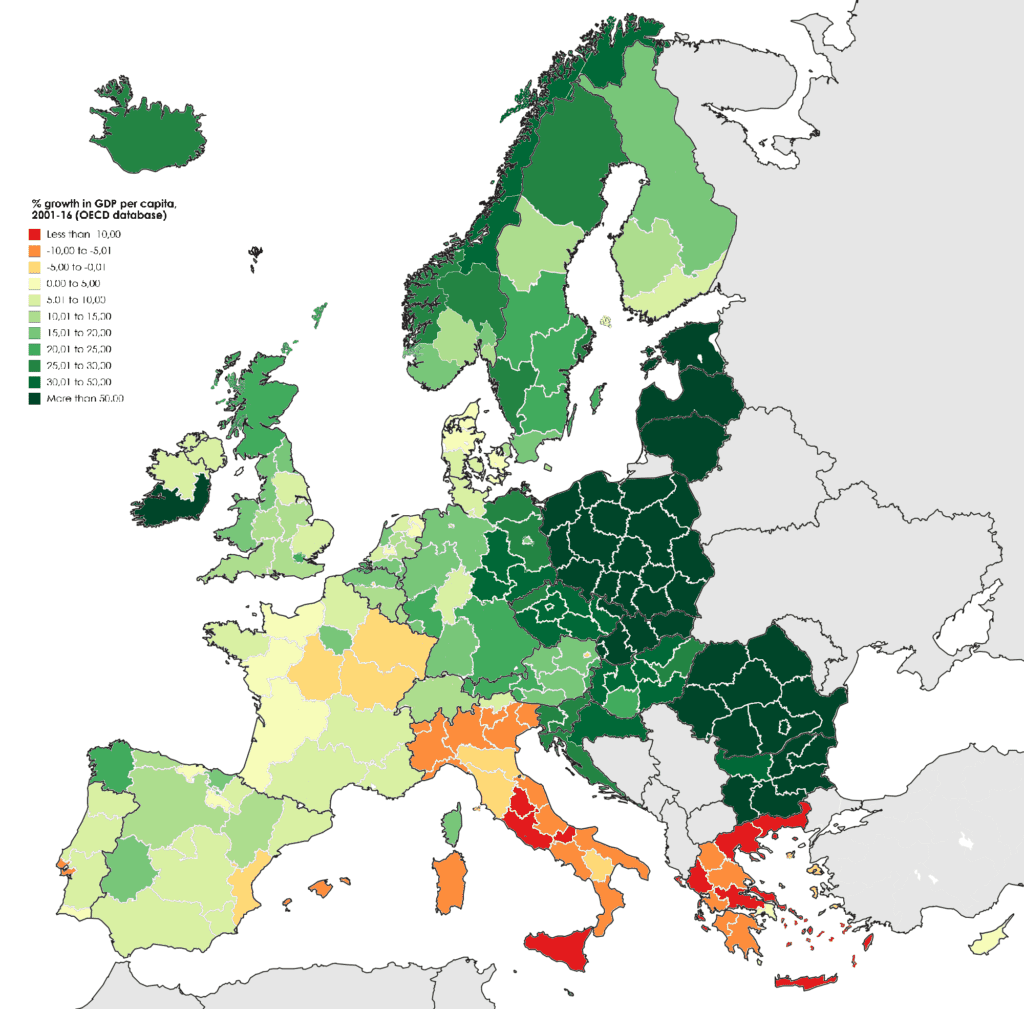

The past quarter-century has been the most successful in Poland’s history economically wise.

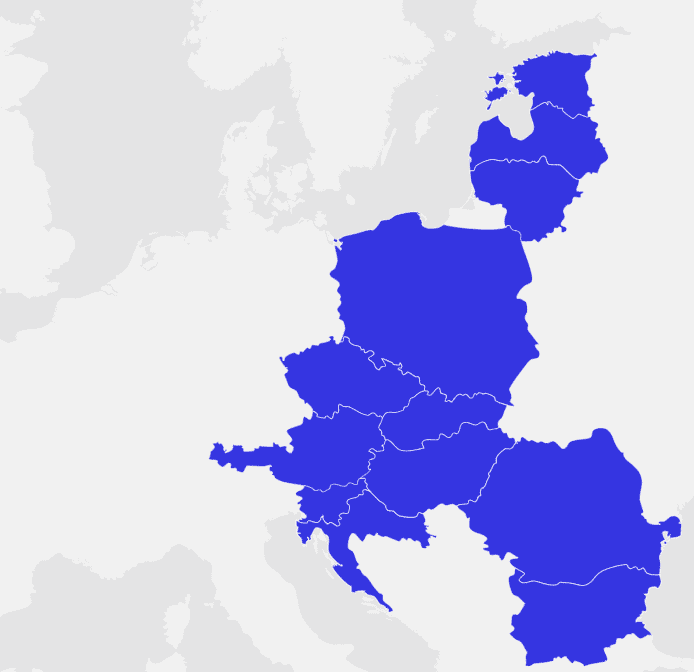

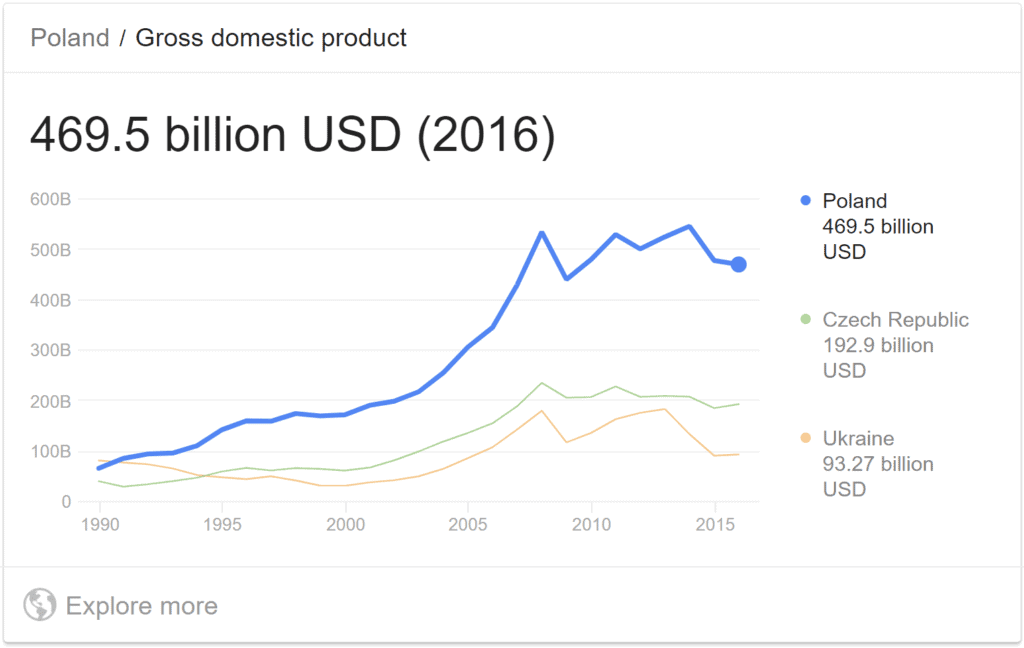

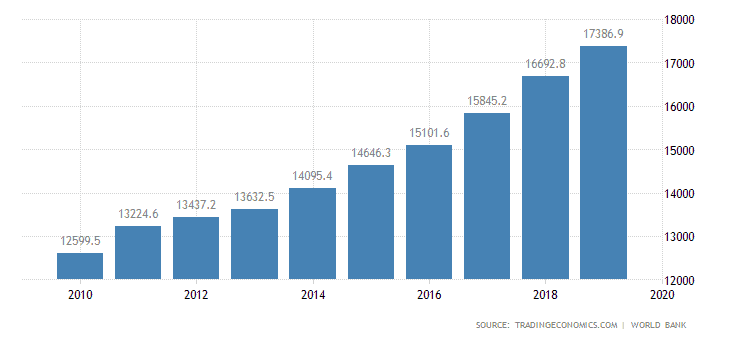

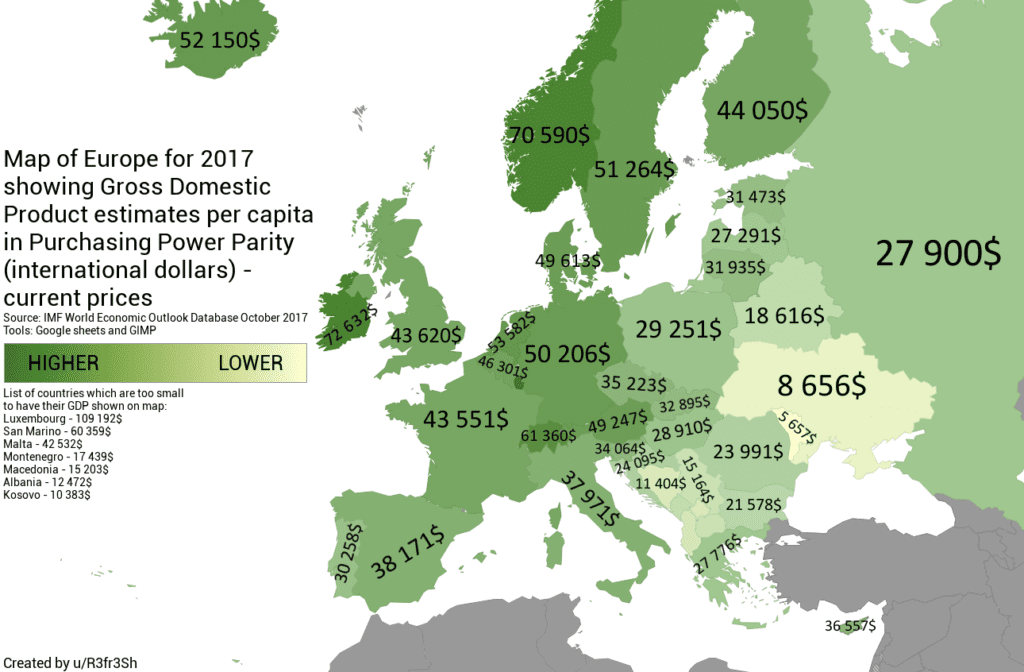

GDP per capita grew by 150 per cent and now stands at $18,000, the level of wages increased more than the average for G7 member countries while the economy continued to grow during and after the 2008 crisis, reaching +5 per cent for 2018 and 4.5 per cent for 2019. Even with Covid, Poland managed to grow a full 1% so far in 2020. The private building sector is expanding rapidly, thanks also to improvements deriving from new infrastructure networks, whose construction is facilitated by the inflow of European funds, amounting to 106 billion euros between 2014 and 2020. Prestigious global companies such as IBM, Citi Group and Crédit Suisse are transferring part of their services to Poland, thanks to the high digital litteracy and expertise. Even the ageing population (mainly due to Polish youth leaving), declining birth rates and emigration to other countries by citizens has not succeeded in curbing the Polish economy, which has offset the losses with the inflow of at least 1.1 million Ukrainians since 2014, a population that was historically, ethnically and culturally similar to Poles and integrated without much difficulties.

Until not many years ago the Polish worker was the stereotype of the EU economic migrant. The incredible boom known by Poland, an economy that has been able to multiply threefold its size in less than twenty years has changed the picture in a radical way(in 2001 the nominal GDP was worth 190 billion dollars, today it is around 600 billion), . With an unemployment rate down to 3.3%, roughly the threshold considered structural, Warsaw is now attracting human resources from other European countries, not only the poorest Eastern partners but also Western economies exporting highly skilled unemployed, such as Spain, Greece and Italy.

Although the most obvious opportunities of the 1990s have gone— Poland is now well stocked with hardware shops, coffee bars, banks and law firms—the country still does offer interesting, if narrower, niches. Still, the model is changing. Polish salaries are rising sharply and, when cost-of-living differences are taken into account, are starting to earn similar amounts to what they would in Western Europe. The maturing economy means that new businesses in Poland now have to find niches similar to what would work in Western Europe and the United States.

It didn’t take a capitalist genius to figure out that Poland would need grocery shops, shopping malls, pleasant apartment buildings, and clean automobile dealerships. But now that Poles are about two-thirds as rich as West Europeans, the rest of the climb will be tougher. Yet Poland continues to defy the predictions and its growing rates can predict a level of development similar to most West EU countries by 2035.

There are many reasons for this success story: from a privatisation programme conducted with transparency and rigour, which has not created oligarchs like elsewhere, to heavy investment in education; from debt restructuring to a very business-friendly tax policy, with a 19% tax on profits, a reasonable rate in Europe, which has led many multinationals to relocate divisions to Poland.

Not to be understated, the advantage of staying out of monetary union is more in a relatively weak currency, which favours exports and foreign investment. One may think that staying out of the Eurozone would allow governments to be fiscally irresponsible, given the absence of other parameters to be respected. Quite the opposite: with a public debt of less than half of GDP, Warsaw has much more virtuous public accounts than most Eurozone countries, which in turn contributes to the stability of the economy.

In fact, progress in every area of life, from the quality of the roads to the types of cars people drive and the salaries they earn, has been staggering. But that still leaves Poland as one of the poorest – relatively- countries in the European Union, one that has seen as many as two million people leave over the last decade to seek their fortunes in the wealthier countries of Western Europe. Frustration at that gap is one of the drivers behind Law and Justice’s rise, but the party’s populist policies—from lowering the retirement age to trying to impose higher taxes on foreign retailers—could make it more difficult for Poland to continue its exceptional run of economic growth in the future. Yet this is changing, as Polish people are coming back with new opportunities being created in Poland.

And last but not least, control of the influx into the Polish work market has allowed the wages to rise with the economy, which, taken with the recent year low inflation, has allowed Poles to obtain better conditions and raise consumer purchasing power.

What can ruin a rise that seems so unstoppable?

A demand for labour that has now outstripped supply in a worrying way. “In the last three years we haven’t been able to hire a single Polish person,” Aleksandra Rucinska, human resources manager at Tawo, a textile company that relies on clients of the Ikea weight.

The main reason for this is very low population growth, a problem shared by neighboring Hungary and, more generally, by the entire former communist area, where the International Monetary Fund fears a quarter decline in the workforce by 2050. In 2019, there are currently 9.7 new births per thousand inhabitants, down by 1.46% compared to 2018, and the policies to relaunch the birth rate of the conservative government of Freedom and Justice have not yet had the desired effect.

What makes these policies ineffective is in part the scale of migration in past years, when hundreds of thousands of citizens of child-bearing age left the country to start families abroad, leaving behind a homeland where the average age is increasingly high. Without taking into account ethnically Poles that descend from past immigration – mainly Americas and France- , there are around 6 to 8 millions Poles in the world that were actually born in Poland, with around half of them being under 35.

In recent times it has mainly been the arrival of workers from Ukraine and Belarus that has been supplying part of the demand for labour, but it is a flow that has started to run out, so much so that some sectors in search of low-skilled personnel, such as the catering sector, have been forced to look for resources in Nepal or the Philippines in the last ten years. This however is not viable on the long term, as both communities, though providing qualified and competent workforce, only desire returning home on the long term, as it has been shown by studies on those communities specifically.

The Polish public and government is very aware of this problem. In the past, the government has been switching between two policies : trying to set up a international polish diaspora, and making the Polish diaspora (which, for the post part of them, are still Polish national and have strong ties with Poland) come back home. Yet recently the government has recently changed policies and new policies have been laid out by current Prime Minister, Mateusz Morawiecki.

“Give us our people back”

“Give us our people back,” Prime Minister Morawiecki said during a BBC interview on the sidelines of Davos 2019. The remark was obviously, at the time, directed to the UK where nearly a million Poles currently reside. “More and more are coming back,” he said earlier in the interview. “I’m very happy about that because there is the lowest level of unemployment in Poland, 5-5.5% GDP growth, one of the strongest in the European Union.” He has made the plea on numerous other occasions and the message has been echoed throughout his government. An official social media campaign entitled ‘We Are 60 Million’ was launched in July to reach out to the diaspora in an attempt to entice some of them back.

But why the urgency?The answer is that the Polish economy is simply starved of labour. An unemployment rate of 3.58% and a 4.0% projected growth rate for 2019 spells one outcome: labour crisis. And with July’s business sector wages showing a 7.4% YOY increase, there are little signs that the labour supply will catch up with demand in the near future. As a stop-gap measure, the government has become the EU’s number one issuer of work permits to non-EU workers, the majority of which arrive from across the border in Ukraine.

But there is a far larger problem looming in the long term. Like the rest of the OECD, Poland’s 60-and-over segment of the population is growing at a faster rate than the working population (15-to-59). A 2015 McKinsey report predicted that the old-age dependency ratio between the retired and working population will grow to 30% by 2025, representing a 10% jump on 2012 figures. This is where the government 500+ family support programme comes into play, except the effects won’t be seen for at least 20 years. Given the circumstances, it is easy to see why the government would like to welcome back the millions of emigrants who have spent the past 15 years honing their skills abroad, some of them in the world’s leading institutions and companies. But have they received the message? Do they even want to come back?F

The PLUGin Foundation, a think tank dedicated to ‘the Polish innovation diaspora’, has attempted to answer these questions with their first survey entitled ‘e-Migrants’. As the title suggests, the recurring survey is mainly designed to “identify, examine and describe the polish ‘innovation diaspora’ spread all over the world,” although more than half of respondents worked in other fields such as finance (7.5%), consulting (5.4%), marketing (5%) and the physical sciences (4.2%). The majority were located in the UK (32.5%), Germany (16%), the USA (11.1%) and Spain (9.1%).

As a first hit-out, the project presented some interesting results, producing a detailed map of the cohort over four main areas: characteristics, experience, national identity and repatriation. While 67.5% still embraced their Polish identity and 48.8% of respondents said that they think about returning home, 56.8% admitted that a potential return was only a loose thought. Indeed, an overwhelming majority (82.9%) perceived their emigration as a permanent solution. The two top factors discouraging their return were the political situation (73.9%) and the state of the economy (42.3%) in the country. While this data is representative of only Poles working in the innovation dispora, it gives us clues . In short term, we can ponder based on the data that possibly one out of two will be returning Poland if the economy keeps getting better, which is more than a mere possibility.

Upon their return, expats often come back as advanced managers armed with invaluable experience, training, connections, language skills and confidence, which they, in turn, inject into local organisations or their own startups. The startup world is fuelled by people with international experience. Startup Poland’s report on Polish startups indicated that 50% of all Polish startup founders have experience of living and working abroad,” he added. That’s a huge number and proves that living abroad … opens up your brain and teaches you the kind of thinking needed for true entrepreneurship. Not to mention contacts.

A sound system yet to be overhauled

Blue Europe advice

Yet this doesn’t mean that policies can’t be implemented to increase attractiveness for Polish nationals abroad to return to Poland. Poland has already taken two steps in the right direction as to help his population return home, and we at Blue Europe think it should overhaul its program.

The Polish government has already considerably cut all new arrival from outside Europe, especially from Asia, which previously supplied low skill workforce. The policy aims to increase average salaries in Poland, by decreasing offer, which is of course a good idea. This organic growth has proven to be very efficient and sustainable. Poland it is inside the EU, and has to deal with its partner choices. Current policies, mainly from French and German pressure, do not push in this sense. The Polish government could find, at a long term, partners in Europe that would help to maintain and lower immigration, with a long term goal to no new arrival of populations and immigrants in Europe, other than returning Poles.

In this regard, the Polish government may also think about setting up a high qualification technical workers programs from countries and regions inside the EU that overflow with them, such as Italy, rural parts of France, or even some parts of Germany and Spain. This short term immigration would help to cover some limits that Polish economy is encountering. Poland has also a very important opportunity with neighboring workers from Belarus, Ukraine and maybe Romania. Please check out our deep dive coming out next week on Belarus demographics for more informations.

At the same time, the Polish government could give to non-EU non-qualified workers the possibility to migrate back to their country with dignity and good possibilities. As such, a leaving cash bonus for foreign nationals returning to their native country – with of course due human rights guarantees – seem an effective and fair solution.

Yet we think that Poland could add another level to its policies, which is maintaining entry level jobs with low qualification at all cost. Most Western European economies, especially Latin countries and Germany are ridden with youngsters getting too late in the economy, sending them in often ten year long studies, because there are no entry job, or if they do exist they are paid very little. In one of the most expensive capital of Europe, Paris, getting a minimal wage employment as a waiter is considered a privilege . Polish economy is extremely efficient also thanks to the rapid integration of workers in its economy. Those entry jobs would be indispensable for any returning population, as they would serve as a transition jobs for retuning Poles before being able to correctly find a qualification more fitting to their career experiences.

All economy sectors contribute to the existence of this state of grace, but the low taxes and low ownership business concentration is also very critical to this same state. In this regard, Polish public policies are satisfactory and work very well with EU framework, especially as to antitrust and public accounts directives. If the Polish government will decide to continue its policies, this will prove a strategic asset in the future. So far, it has done so, even with Covid-19 problematics, a rare feat in Europe.

This can be achieved at multiple levels, which we will not discuss in detail. While allowing non-EU non qualified workers to return home, as we said previously, would allow a lot of entry job to be vacated for Polish and EU nationals, this will not offset the necessary and ongoing industry automation. The automation will destroy, with no going back, tens of thousands, maybe hundred of thousands jobs.