North Macedonia, a landlocked country in the Balkan Peninsula, sharing its borders with Serbia, Bulgaria, Greece, Albania, and Kosovo. With an area of nearly 26,000 km² and a population of about 2 million, it is a country rich in diverse cultural heritage and complex history.

Today, North Macedonia is known for its picturesque landscapes, rich historical sites, and cultural diversity. The majority of the population are ethnic Macedonians, predominantly Orthodox Christians, but there is also a significant Albanian minority, along with other ethnic groups. The capital, Skopje, located in the northern part of the country, is the cultural and economic heart of North Macedonia. The national flag, featuring a yellow sun on a red field, symbolizes the new dawn of independence and unity.

The Macedonian government applied for EU membership in 2004 and obtained candidate status the following year, the same status recently granted to Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia. But until recently the next step had never been taken: the start of accession negotiations, for which the approval of all EU member states is required.

A glance at the history of Macedonia

The region known as Macedonia has been inhabited since prehistoric times, with its history deeply intertwined with the ancient kingdom of Macedon. This ancient kingdom rose to prominence under the rule of King Philip II and his son Alexander the Great in the 4th century BCE. Their reigns marked the expansion of the Macedonian Empire across a vast territory, spreading Hellenistic culture far and wide. Following the division of Alexander’s empire, the region saw a series of rulers, including the Romans, Byzantines, and eventually the Ottoman Empire, which left a lasting influence until the 20th century.

In the 20th century, the territory became part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, later known as Yugoslavia. The region experienced significant shifts and transformations during both World Wars, with various nationalist movements vying for independence or greater autonomy. It wasn’t until the disintegration of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s that North Macedonia emerged as an independent state, officially declaring its independence on September 25, 1991, under the name of the Republic of Macedonia.

The Name Dispute with Greece

The choice of the name “Macedonia” was a source of significant contention, particularly with Greece, due to the historical and geographical implications of the term. Macedonia historically refers to a larger region that extends into modern-day Greece and Bulgaria, and the name is closely associated with the ancient kingdom and its notable figures like Alexander the Great. This led to almost three decades of diplomatic disputes, negotiations, and international mediation, including efforts by the United Nations.

It wasn’t until June 2018 that a landmark agreement, known as the Prespa Agreement, was reached between Greece and Macedonia, leading to the country’s official renaming as North Macedonia on February 12, 2019.[1] This resolution paved the way for North Macedonia’s further integration into international communities. The country officially joined NATO on March 27, 2020, and has since been moving towards European Union membership, with official negotiations accelerating.

A steep path towards the EU membership

North Macedonia is closer to joining the European Union, but not all of its inhabitants are happy about it. The opening of accession negotiations for the Balkan country, together with Albania, comes after the signing of a memorandum of understanding between the Macedonian and Bulgarian governments, which – after the resolution of the “name issue” – kept the entire process blocked.[2] The terms of the agreement, however, are considered by many to be humiliating: while negotiations have already started in Brussels discontent remains in Skopje.

Initially, as mentioned, it was Greece that barred the way, having Macedonia to change its name to North Macedonia in 2018, as the Greeks consider the toponym a region of their country. The following year, three states, including France, opposed the will of the other 25, stopping the start of negotiations.[3]

In June 2022, of the 27, only Bulgaria was opposed, due to a bilateral dispute. In essence, this is a historical dispute with identity implications, as an analysis by the think tank European Stability Initiative (ESI) points out,[4] which considerably slowed down the process and was only overcome at the price of a discussed compromise.

In October 2019, the Bulgarian government, led by then Prime Minister Boyko Borisov, had set its conditions for accepting the start of negotiations. A thorough review of the common past is needed: a joint historiographical commission should establish that the Macedonian population is descended from the Bulgarian population and that after World War II it underwent a process of deconstruction of its identity, supported by a robust anti-Bulgarian narrative.

This nation-building operation was allegedly promoted by Tito’s Yugoslavia with the establishment of a Socialist Republic of Macedonia within the Yugoslav federation. The same, according to the Bulgarians, should be applied to the Macedonian language, simply a variant of their own. This ‘error’ of historical interpretation should be corrected with a new version of the common past, to be presented to the public and taught in Macedonian schools. The Bulgarian demands were included in a six-point bilateral protocol in 2021.

The document was reviewed by the Birn Balkan expert team.[5] It contained the recognition of a Bulgarian minority on Macedonian territory (about 120,000 people, claims the government in Sofia), the fight against alleged anti-Bulgarian hate speech, the admission of common ethnic roots, and even the identity of the anti-Ottoman revolutionary Goce Delcev, whom both Bulgarians and Macedonians consider their national hero. All very thorny issues for public opinion, and consequently for the authorities, in North Macedonia.

A final agreement was only reached on Sunday 17 July 2022 with the signing of a final text of the protocol by the foreign ministers of the two countries.[6] The impasse was broken by the intervention of France, which held the rotating presidency of the EU Council until the end of June 2022.

Conflicting domestic reactions: a costly EU accession?

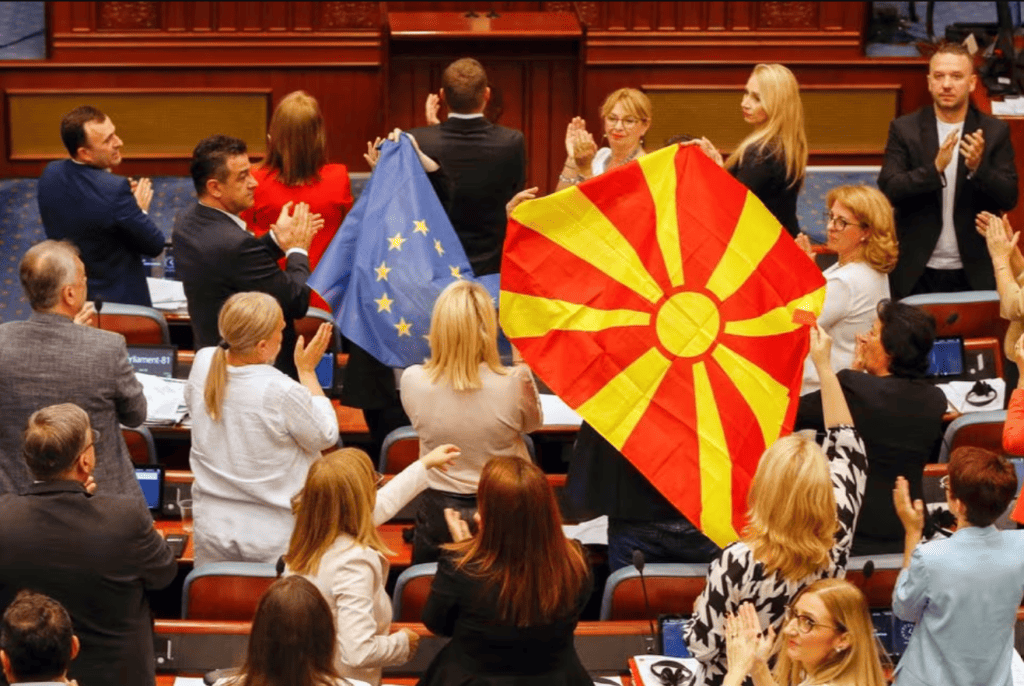

A compromise proposal drafted by the government in Paris was approved first by the parliament in Sofia and then, with much more resistance, by that in Skopje. Among other things, it provides for an amendment to the Macedonian constitution precisely to guarantee recognition and rights to the Bulgarian minority. Perhaps for this very reason the ‘French proposal’ did not please a large part of the politicians and population of North Macedonia, which threatens to undermine the country’s path to the Union.

The Macedonian parliament approved it on 16 July 2022, but split: 68 out of 120 deputies voted in favour, the others abstained, and many of those against walked out of the chamber in protest at the time of the vote. The enthusiasm of the president of the government, the socialist Dimitar Kovacevski, for the opening of negotiations after ‘17 years in the waiting room’ was counterbalanced by the coldness, or open protest, of other Macedonian politicians.

Additionally, two members of the governing majority did not support the proposal, while both the left-wing Levica and the nationalist right-wing Democratic Party for Macedonian National Unity (Vmro-Dpmne) came out against it.

The aversion of some political forces rides on and responds to a rather widespread feeling in North Macedonia. Proof of this are the numerous street protests held in Skopje around the time of the vote, coinciding with the visits of Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and European Council member Charles Michel.

The protesters expressed the need to protect Macedonian identity, which they said was endangered by the conditions imposed by Bulgaria.[7] The choice of words in a passage of the speech with which von der Leyen announced the start of negotiations does not seem accidental then: [8] an agreement on the relocation of Frontex agents, which forms part of the cooperation between North Macedonia and the European Union, will be “translated into the Macedonian language, no footnote, no asterisk, on an equal footing with all 24 EU languages.”

The start of negotiations marked a turning point, but the path to accession promises to be long and above all conditional on what will happen in North Macedonia, where the outcome of the constitutional revision process is not a foregone conclusion.

At the national level, meanwhile, the multi-year stalemate before and the strict conditions required now could undermine the will of a population that tends to be pro-European, or at least increase its scepticism. A survey by the Institute for Democracy, covering data collected in 2021, indicates that more than two-thirds of Macedonians are in favour of EU membership. About a third of those surveyed, on the other hand, believe that it will never happen. Brussels and Skopje are working to make them reconsider.[9]

Future prospects for the EU accession of North Macedonia

The European Commission’s annual reports are crucial in assessing the progress of candidate states. The 2023 EC Progress Report has pointed out significant concerns over North Macedonia’s progress, marking a departure from the more positive evaluations in recent years.[10] The report candidly urges the country to move from declarative support to tangible action, particularly in areas of domestic reform, rule of law, and corruption combat.

North Macedonia has seen advancements in aligning its foreign policy with EU positions, notably in its response to Russia’s war against Ukraine and its role as a chair of the OSCE. However, the internal landscape presents several challenges. The judiciary is a particular area of concern, with negative assessments highlighting the lack of independence and integrity, as well as susceptibility to political influence. Corruption remains a pervasive issue, exacerbated by legislative changes that have reduced penalties for related crimes.

The political environment is deeply polarized, leading to legislative gridlocks and weakening of democratic institutions. This polarization has hindered the functioning of parliament and delayed key appointments, slowing down the reform momentum necessary for EU accession.

Civil Society and Legislative Reforms

The role of civil society organizations is acknowledged as crucial yet underutilized. While they operate relatively freely, there is a call for enhanced engagement and improved cooperation with government bodies. Gender equality and human rights remain pressing issues, with some progress in legislation against gender-based violence but an ongoing struggle against the “anti-gender” movement.

Economically, North Macedonia demonstrates a good level of market economy functioning but faces challenges like infrastructure gaps, investment shortages, and a significant informal sector. The country has made strides in combating organized crime and managing migration but must continue to address these complex issues.

Constitutional Changes and EU Integration

A significant hurdle in North Macedonia’s EU integration path is the proposed constitutional changes, a condition following Bulgaria’s veto in 2020. These amendments aim to recognize additional minorities within the country, including the Bulgarian people, a move met with considerable domestic opposition. The constitutional amendments are yet to be passed, with the parliamentary elections in 2024 likely influencing their fate. While the EU underscores the amendments’ importance, the current focus in light of broader rule of law and corruption issues seems to lie elsewhere.

As North Macedonia approaches its 2024 parliamentary elections, the EC report underscores the imperative for the country to maintain its momentum towards meeting EU accession criteria. While challenges persist, there is cautious optimism, especially given the EU’s renewed commitment to enlargement. The country’s journey reflects the intricate balance between domestic reforms, regional relations, and alignment with European standards, a path fraught with obstacles but also opportunities for transformation and integration into the European community.

Sources

-

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jun/17/macedonia-greece-dispute-name-accord-prespa ↑

-

https://apnews.com/article/albania-ursula-von-der-leyen-european-union-edi-rama-c302c3fb6329185f30e6952a906b201a ↑

-

https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-ministers-once-again-fail-to-reach-deal-on-north-macedonia-and-albania/?ref=yeetmagazine.com ↑

-

https://www.esiweb.org/newsletter/elephants-skopje-balkan-turtle-race-and-ukraine ↑

-

https://balkaninsight.com/2021/10/19/birn-fact-check-can-north-macedonia-meet-bulgarias-six-demands-for-breakthrough/ ↑

-

https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/n-macedonia-votes-resolve-dispute-with-bulgaria-clears-way-eu-talks-2022-07-16/ ↑

-

https://www.rferl.org/a/thousands-protest-north-macedonia-bulgaria/31926735.html ↑

-

https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/STATEMENT_22_4602 ↑

-

https://idscs.org.mk/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/A5_Analysis-of-public-opinion-on-North-Macedonias-accession-to-the-European-Union-2014-2021ENG-1-1.pdf ↑

-

https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/north-macedonia-report-2023_en ↑