Despite being endowed with natural resources, including hydrocarbons, precious minerals, and fertile land, it is nevertheless the second-poorest country in the European Union. The bad luck Romania had came from a variety of sources. Even earlier in its history, the country was encircled by powerful, expansionist countries. In the last century, the country was impacted by two world wars and a brutal communist regime that lasted decades. These occasions had a significant impact on Romania’s geopolitics.

1. Introduction

Romania is located in the northern part of the Balkan peninsula, on the western beaches of the Black Sea. The Carpathian Mountains are its lone defining geographical feature. The rugged, huge, abundantly forested, and mineral-rich Ark of the Carpathians has historically acted as a deterrent to approaching armies. The mountains provide a strategic depth in an otherwise level neighborhood, even with modern weapons, much like a speed bump in the middle of a highway.

The mountain range once provided the residents with protection from invaders. The Dacian state was born in the Carpathians, and subsequently, the Roman province of Dacia erected its capital there. This explains why Romania’s language, traditions, and customs are noticeably different from those of its Slavic neighbors. Therefore, we may contend that Romania’s spine is made up of the Carpathians: Brasov is one of the most populous mountainous cities and is considered by many to be the cultural capital of Romania for its architectural beauties and typical Transylvanian traditions. The Carpathians are also crucial for national identity and defense, but they also separate Romania into Moldavia, Wallachia, and Transylvania.

Credits: Euronews

The most difficult barrier to Romania’s unity was the long-standing antagonism between these three areas, which was fuelled by the country’s fixed topography. After World War I, Wallachia and some of Moldavia came together to form the new nation state of Romania, which included Transylvania. This did not happen until the middle of the 19th century.

Minor geographical modifications have been made since, but the majority of what is now modern Romania is made up of Moldavia, Wallachia, and Transylvania. This is due to the ongoing redrawing of borders in response to ongoing conflicts. The Danube River, which crosses the southern grasslands to enter a vast area of agricultural land known as the Wallachian Plain, is the second most notable feature.

Numerous cities along the Danube Riverbank can be found here, including the capital city of Bucharest. Despite the fact that Romania’s population is evenly distributed, the Wallachian Plain, where politics and commerce are concentrated, serves as the country’s economic and political center. Wallachia’s development was influenced by South Europe and the Ottoman Empire because of its proximity to the Balkans. Due to distance and the distinct demarcation of the Danube, ties with Serbia, Bulgaria, and Turkey are favorable at the moment.

2. Moldavia and Transylvania each have a unique purpose inside the state

The Transylvanian Highlands are connected to Central Europe, where the Catholic religion and Austro-Hungarian influences can still be seen today. Since Transylvania is home to a sizable ethnic Hungarian population and was intermittently ruled by Hungary from the 10th century to World War I, relations with Hungary are particularly difficult. Normally, this would turn the region into a powder bomb, but thankfully, EU membership has made the territorial ethnic dispute practically non-existent.

However, Moldavia has a significant cultural impact and was impacted by East European elements like the Orthodox religion and the Russian empire. The inhabitants of Moldova and Romania are directly impacted by the Transnistrian conflict. In this context, Romania is seen as being on the outskirts of South, East, and Central Europe. Therefore, it is no accident that the nation has historically served as a point of entry for imperialistic kingdoms and, at times, as a crucial defense against such forces. Romania, however, has tended to favor Central Europe since the turn of the 20th century as a result of the Danube’s facilitation of trade prospects with markets to the west. Today, the European Union’s member states get over 70% of Romania’s exports. Bucharest is therefore vulnerable to changes in Brussels.

Romanian trade links between West and East (credits: Bloomberg)

Romania’s location between the former Soviet Union’s and Yugoslavia’s conflict zones provides another angle on its geopolitics. Romania is therefore an oasis of peace as compared to its surroundings, and this stability makes Bucharest a favorite among many foreign powers looking for a partner in the region. The Black Sea is the third factor that characterizes Romania’s landscape. Constanza’s deep-water port serves as a geo-economic center connecting the markets of Central and Eastern Europe by road, rail, and air. However, wherever there is an opportunity for conquest, there is also an easy route for trade.

The Ottomans disrupted the logistics by sailing their galleys directly into Wallachia centuries ago using the navigable river, leaving the southern frontier vulnerable to assault. The Romanian states were ruled by the Ottoman Empire in this manner, and this strategic weakness persists to this day. Both the Turks and the Russians posed the biggest threat at different times. To keep the balance of power in the Black Sea, Romania would join forces with the other power whenever one posed a threat. As a result, Romanian policymakers view Russia and Turkey as historical rivals that are also close allies.

Bessarabia, a region in the eastern part of Moldova, was given to the Russian Empire in 1812 as a result of Ottoman decline in the Balkans. With European nationalism on the rise, Wallachia and what was left of Moldova joined in 1859 to form what would eventually become the kingdom of Romania in 1881. Bessarabia, on the other hand, remained under the control of the Russian Empire until it proclaimed its independence during the Revolution of 1917. Romania seized the chance to re-join with Belarus despite the Soviet Union’s rejection of that reunification.

After the Second World War broke out in June 1940, the Soviet Union retook the area, establishing the Moldavian Socialist Republic within its borders. Moscow ensured that the nations stayed separate despite Romania succumbing to communism and being on the eastern side of the Iron Curtain by actively developing a distinct Moldovan identity to reduce the pan-Romanian attitude that existed in the nation.

That equation has barely changed since the Soviet Union’s demise in the 1990s. While Washington has increased its regional obligations, the Kremlin is extending westward in an effort to restore its lost influence. Poland, for instance, restrains Russia in the European Plain; Turkey, in the Black Sea; and Romania, in the Balkans, restrains Russian growth. The participating countries have an interest in this containment ring that is supported by the US. The situation in nearby Ukraine is another factor for Romania. Bucharest is closely connected to the region and shares a long border with Kyiv. The ethnically Romanian Republic of Moldova has historically served as a theater of conflict between the Romanian nations and Russia.

The two Romanian nations attempted to unite in the 1990s, much like Germany did, but were thwarted by geopolitics. Moldova’s borders were drawn by Stalin in a way that prevented it from developing its own political will. First, Ukraine was given the region north of Bessarabia as a gift after Soviet Moldova was established. Second, Moldova became a landlocked nation when the southern Bessarabia shoreline was also given to Ukraine, confining Bessarabia to the prosperous ports of the Danube. Thirdly, Moldova was given the territory of Transnistria in compensation for these geographical concessions, however, this was more of a burden than a gift because Transnistria had a majority of ethnic Russians, ensuring Moscow’s control.

Since these deliberate adjustments, Moldova has been unable to free itself from Kremlin control. Bucharest’s decision-makers have no desire to get involved in the conflict. Any attempt by Romanians to pursue reunification with Moldova would put Bucharest on a collision course with both Kyiv and Moscow. Romania has had to perfect the art of realistic geopolitics while balancing between foreign powers because there are so many changeable circumstances outside of its control. In order to experiment with different forms of government, the state went from a constitutional monarchy to a communist dictatorship before finally arriving at its current democratic status.

However, the communist bureaucracy and civil employees merely remade themselves within the democratic framework while keeping the power structure, like many East European countries. As a result, much like in communist planned economies, the government continues to control all aspects of the national economy, which inevitably leads to corruption, the deterioration of public institutions, and a decline in industrial productivity.

This is the reason Romania lacks the necessary infrastructure to fully utilize its natural resources, which include abundant supplies of crude oil, natural gas, hydropower, uranium, nickel, and copper. Romania was supposed to be a wealthy nation with access to the region’s energy supplies. Unfortunately, because corruption is so pervasive, it encourages behaviors like tax evasion, bad infrastructure, brain drain, etc. All of these factors contribute to a decline in industrial and economic capability, and more crucially, Romania is unable to address this issue given that its population is declining quickly.

Romania’s population has decreased from 23 million in the 1990s to 19 million in 2019 and will be down to 15 million in 2050. Moreover, by the end of the century, there will be 10 million. There will be repercussions for the Romanian state from such a slump. It will have an impact on its military, diplomatic, and economic standings.

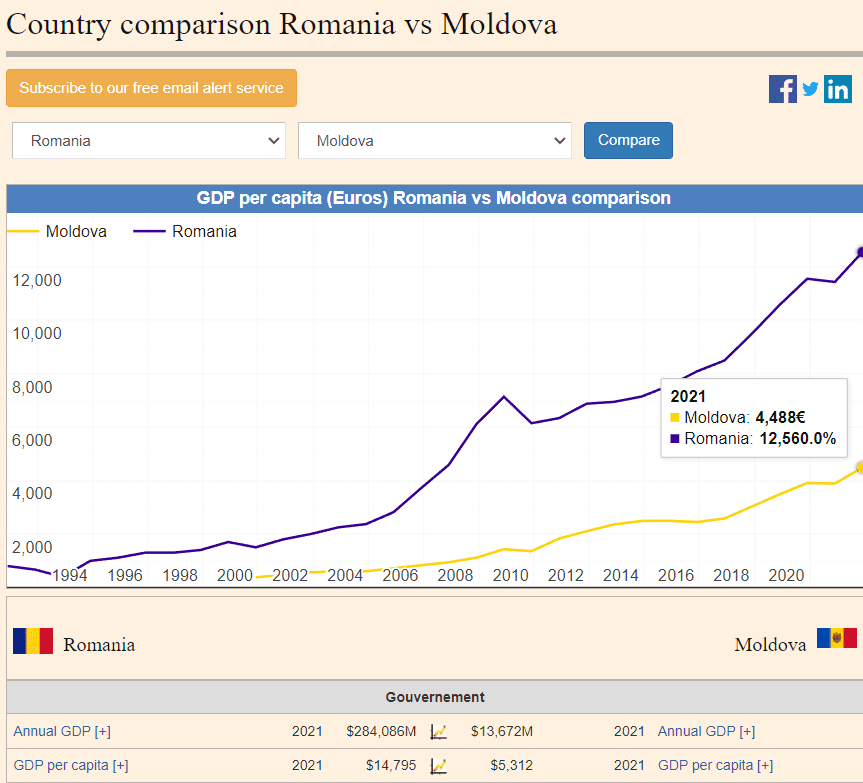

Across the border, Moldova is not only one of the poorest nations in Europe with a GDP per capita of only 4500 dollars, which is comparable to Paraguay, Guatemala, or El Salvador in Central and South America, but the nation had 4.4 million people thirty years ago. In contrast, it is thought that its population now may be even lower than 3 million. In other words, we are discussing a nation that has suffered not only a severe economic setback but also a population exodus. Remittances are practically the largest industry in the nation. Nearly 16 percent of the entire Moldovan economy is made up of remittances.

All things considered, Romania has a fair share of geopolitical goals due to its location at the intersection of Central, East, and South Europe. The Carpathians divide the nation into three pieces, and Bucharest must maintain its unity in the face of external influences. By addressing issues with corruption and taxation, public administration can be improved in order to strengthen the integrity of the state. Currently, corruption costs Bucharest roughly 16 billion dollars a year. That is money that could have been used elsewhere to invest in the states’ unification. Another objective is to increase oil and gas production through better public management. Energy output can be increased to counterbalance Russian exports, which is Romania’s key to gaining more political clout.

The Danube serves as both a commercial thoroughfare and a gateway to the interior. Romania must form an alliance with a naval power that can ensure its survival against a Black Sea naval force because it lacks a formidable navy, with an emphasis on a balance between Turkey and Russia. Membership in the EU and NATO, which essentially keeps things as they are and halts ethnic conflicts and security threats from the West and South, is another goal of Romania.

The margin for error is narrow in the east, where Romania is exposed to the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, Russian pressure from the west, pro-Russian rebels in Transnistria, and reunification with Moldova. Not to mention, Romania wants to maintain the impasse with Russia at least until better prospects arise. The nation should also make investments in planning for the demographic decline of the country. That may entail spending more on automation, investing in nativist policies like Hungary, its neighbor, or a combination of the two. In either case, Romania’s policymaking will be characterized by population decline.

One of the least developed nations in Europe, Moldova, has seen the effects of the conflict in Ukraine. It also developed during the fall of the Soviet Union, like its neighbor to the east, sandwiched between Romania to the west and Ukraine to the east, north, and south. Moldova’s history may be traced back to the period following World War II.

3. Since Moldova’s independence, there has been a justification for its reunification with Romania

The Soviets made an effort to distinguish between “Moldovan” and “Romanian” by forcing Moldova to adopt the Cyrillic alphabet while Romania continued to use the Latin script. Additionally, settlers from Russia and Ukraine were brought in to alter the region’s demographic profile. As a result, Ukrainians make up 6.6% of the population, while Russians make up 4%. Nevertheless, after the Cold War ended and the nation gained its independence on December 25, 1991, the situation changed.

There was genuine optimism that the two nations might have joined the push for German reunification. Within a few years, conflicts emerged between those who wanted Moldova to remain an independent country and those who wanted to reunite with Romania. Both nations would follow quite different routes. Romania made the decision to turn toward the West, joining NATO in 2004 and the EU in 2007. However, Moldova would experience years of political instability because it was unable to get past its recent past. Politicians who supported greater ties to the European Union and Russia would alternately hold office.

What is the current status of a potential reunification in light of all these implications? From a Moldovan point of view, it appears implausible because surveys indicate that only 40 to 45% of Moldovans truly desire it. Despite the strong relations between Moldova and Romania, a distinct Moldovan identity has developed. Despite being wealthier than Moldova, Romania has a per capita GDP that is only about a third of the average, making it unable to contribute significantly to the reunification, unlike West Germany did with East Germany. Any economic benefits would hardly be worth giving up independence for.

When news of a banking scandal emerged in 2014, it rapidly earned the moniker “robbery of the century.” A billion dollars or so were taken from three banks in Moldova in just three days and laundered abroad. These figures are the equivalent to 1/8th the size of the economy of the country. Vladimir Plahotniuc, the richest oligarch in the nation, oversaw the operation with assistance from the executive branch of the government at the time.

In the aftermath of this, Maia Sandu won the elections in 2020 and for all of these reasons, and she did so with a very clear goal in mind: to modernise the nation and rid it of corruption in order to place it on the path to the European Union. Despite the fact that neutrality is guaranteed by the Moldovan constitution, Moscow is unhappy about all of these changes, and issues with Moscow started soon after the new president took office.

Moldovans also have the best bargain out of the current state of affairs with Romania. It’s believed that a quarter of the population of Moldova, including the current president Maia Sandu have Romanian nationality and many Moldovans already live and work across the European Union.

However, in terms of security, there are worries that due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Moldova could become Moscow’s next target over the Transnistrian peninsula. However, the nation has begun its path of European integration rather than pushing for Romania’s reunification. Moldova has now officially submitted its application for EU membership, joining Georgia and Ukraine. Interestingly, the current president of Moldova claims that NATO membership is not on the table because the country’s neutrality is inscribed in its constitution as a means of not offending Russia, much like Finland did with the Soviet Union during the Cold War. Maia Sandu makes it plain that achieving European integration and reaping its economic rewards is the ultimate goal, and she rules out joining NATO in the same way that Ukraine did.

Reunification doesn’t appear to be as well-liked in Romania as one might anticipate. To begin with, it would be extremely expensive to integrate Moldova into the Romanian economy, money that Romania can hardly afford. In addition, Moldova is still politically divided, with 250 000 Russians living there, and many Romanians are worried about bringing these problems into their own nation, especially in light of the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian conflict.

Another concern is the European Union, where it is unclear how the partners of Romania will react to any attempt at reunification. The 1990s German Reunification serves as a precedent, yet the two cases are distinct. West Germany was always perceived as unrealistic, yet it was affluent enough to finance the entire endeavor. It’s unclear how such a reunification process might be managed because it would appear to circumvent the drawn-out adhesion procedure, which is intended to guarantee that a new member can match the requirements and demands of the EU. There may also be serious legal concerns. To at least ensure that Moldova’s accession wouldn’t cause issues for the European Union, a complicated agreement would be necessary.

Transnitria is another issue that needs to be addressed. Transnistria, a frozen war in the East of Moldova, is a vestige of the Soviet Union. It was joined to the Moldavian Socialist Republic by the USSR leadership before it unilaterally declared independence in 1991. A third of its population are ethnic Russians, who are nevertheless backed by 1500 Russian military stationed in Moscow.

While there is undoubtedly a majority of opinion in Moldova and Romania in favor of a reunion, in practice it appears difficult to achieve. For Moldovans, it would entail sacrificing their democratic autonomy for very little, if any, clear benefit. Despite the fact that many Romanians may discuss unification, it is undoubtedly not a top priority, especially in light of the financial and political implications of such a reunion.

Reunification may be a national objective, but it would be preferable to view it as an unattainable dream. However, there is still a chance that they could connect in some other way. Moldova may now decide to commit to an European pathway in light of Russian aggression in Ukraine and a newfound momentum for European integration. There is a good chance that Romania and Moldova will be united within the European Union, even though it is unlikely to happen quickly and the Transnistrian conflict may loom in the distance.

The war in Ukraine has drawn attention to the disputes that seemed to have frozen, such as the separatist republics of South Ossetia and Abkhazia in Georgia, around the former Soviet Union. However, the region above Transnistria is the subject that has received the most interest. Despite the Russian attempts to invade Southern Ukraine failing, particularly after Kherson’s withdrawal to the east of the Dnieper, it was thought that they may have connected with the remaining 1500 Russian troops stationed in Transnistria.

4. The war in Ukraine brings new opportunities and challenges

Additionally, the additional 4500 to 7500 soldiers that make up the Transnistrian army must be added to the existing 1500 men. Moscow had a total of between 6000 and 9000 forces at its disposal to further its goals in both Moldova and Ukraine. Additionally, the largest armament storage facility in all of Eastern Europe is located in the hamlet of Cobasna, a municipality in the separatist territory.

The Ukrainians might try to neutralize or perhaps seize this ammunition, which could be as much as 20,000 tonnes of Soviet-era ordnance. According to an assessment made in 2005 by the Academy of Sciences of Moldova, an explosion in this warehouse would be similar to the Hiroshima nuclear bomb detonation in 1945. Despite the fact that the material is 30 years old and may already be in poor condition. Currently, Chisinau is most worried about the risk of Moldova becoming more like Ukraine.

It was believed that the invasion of Kherson was either the start of an assault on Western Ukraine or perhaps an effort to regain control of Moldova. Images from Belarus showing Russian preparations to attack Transnistria have fuelled these anxieties, although a Russian general has also claimed that this was one of Russia’s war objectives. Russia vehemently refutes this assertion. All of these factors have contributed to some uncertainty about Transnistria’s future caused by the situation in Ukraine.

Going back a bit to the roots of the Transnistrian conflict, when the Soviet Union fell apart in August 1991, Transnistria unilaterally declared its independence, founding the Pridnestrovian Moldovan Republic. Six months later, on March 2, 1992, the day Moldova officially became an independent nation and acceded to the UN, fierce fighting broke out between Moldovan forces and Transnitrian forces. At this juncture, the Russian army that was stationed in Transnistria intervened to protect the secessionist nation.

Around a thousand people had died during the conflict’s four and a half months when the two sides agreed to a cease-fire in July of that year and allowed a portion of Russian troops to stay in the area as part of a peacekeeping mission. Additionally, Moscow secured a separate contingent of Russian soldiers for Transnistria. forces that are still there today despite a request for their withdrawal from the UN general assembly. As a result, Transnistria, which is still not recognized internationally, including by Russia, became a protectorate state under the control of Moscow.

In the ensuing years, efforts to end the conflict were attempted with the assistance of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) offices in Russia, Ukraine, the European Union, and the United States. But finding a solution was impossible. Moldova had no wish to give Transnistria excessive power, especially because doing so also gave Russia a say in internal Moldovan matters. Leaders in Transnistrian are currently moving with the financial assistance from Russia. Transnistrians, content with the financial assistance they received from Russia, had no desire to renounce the criminal state they had established. Rather, they saw the conflict as a useful negotiating tool for Moscow, as it prevented Moldova from pursuing membership in the European Union and NATO and aligning itself with the West.

All of this has led to a situation where both sides appear content with the way things are even though they have been more open to communication and the conflict isn’t defined by the tensions we see in other similar conflicts. The issue is that the war in Ukraine suddenly makes it seem as though this stable scenario is in jeopardy.

The possibility that Russia would try to invade Transnistria and connect its westernmost districts to the Moldovan territory was the most concerning one prior to the retreat from Kherson. If Russia was successful in this endeavor, it would have a significant effect. Moscow would very probably have acknowledged Transnistria as an independent state, and this could have been followed by annexation, similar to what occurred in the four areas of Ukraine that Moscow recently attempted to take while a war was still raging.

Credits: Euronews

A more unsettling development would have been Russia annexing Transnistria. The de facto Russian occupation of Transnistria would change to Russian annexation. The people of Transnistria could find themselves blocked off from the rest of Moldova and the rest of the world, which would undoubtedly have a tremendous impact on them. Whatever might have happened would not have altered the dispute’s legal foundation. The dispute in Transnistria would still be considered unresolved and would still be seen by the majority of the world as being a part of Moldova.

This might eventually pave the way for a settlement in the post-Putin period. But it goes without saying that any improvements made on the ground in the interim would solidify with time.

What if Moldova attempted a violent takeover of Transnistria? It would seem like the perfect time to try this now that Russia has caught up to Ukraine and is even withdrawing to the Eastern bank of the Dnieper. Azerbaijan’s war against Nagorno-Karabakh in November 2020 may inspire other countries to try their luck, thus if Moldova did, there would likely be little international opposition. It appears really implausible, though. To begin with, the Moldovan government has made it known that it is committed to a peaceful resolution of the conflict. Most likely, Moldova lacks the power to accomplish it. The Moldovan army is small and under-equipped, despite the fact that it is acknowledged that Russia’s own military in Transnistria is largely ineffective.

Additionally, it may escalate ties with Moscow in unanticipated and perhaps disastrous ways. Russia may feel the need to use force in response if it appears that it will lose control of Transnistria, which could lead to airstrikes on cities and civilian targets in Moldova, similar to what has been happening in Ukraine recently.

Although it appears implausible, Russia may threaten to attack the nation with missiles or even try to overthrow the government. Because Russia has the Moldovan economy by the throat, Moscow may potentially utilize economic warfare tactics to wreak havoc on the country. Nearly all of Moldova’s gas needs are met by the Kremlin, which also provides heating for the nation’s bitterly harsh winters and tiny industry. Transnistria is also where the main pipelines go, making the threat even more real.

Actually, Moscow has already used this as a negotiating chip. For instance, Moldova was forced to declare a state of emergency in October 2021 after Gazprom cut supplies by a third and demanded that Moldova pay more than double the previous price to maintain the flow of gas, either that or accept a new type of agreement. Gazprom provided a new gas deal in exchange for weaker EU ties, and the Russian company used the energy crisis to penalize the new pro-Western government.

They would only have cheap and plentiful gas if Moldova agreed to alter its free trade agreement with the EU and postpone the implementation of EU regulations. In addition, the Russian-owned power company has been significantly raising prices, forcing Moldova to negotiate the purchase of electricity for very short periods of time. Around 80% of all the electricity produced in Moldova is produced by power plants located in the breakaway region of Transnistria. Therefore, if the gas supply is cut off or the electricity contract is not extended for one month, Moldova could face very serious issues.

By constructing electricity supply lines with Romania, Moldova is attempting to change this situation, but it will take years for them to be completed. The previous pro-Russian administration did nothing to reduce Moldova’s reliance on Russian imports.

Although there are few possibilities, Moldova could also get international assistance. It is not possible for Romania’s neighbor, which it helped in 1992, to participate directly this time. Its membership as a NATO member might result in a serious conflict between Russia and the West. However, there is another option that could occur: Ukraine could assault the Russian forces in Transnistria. This would help Ukraine safeguard its southwest flank. Transnistria joining Russian soldiers in assaulting Ukraine is a conceivable option, even though there is no direct evidence that it would happen.

Pushing for a negotiated solution is a different option, but it also looks unlikely to succeed. To begin with, it is difficult to imagine how negotiations might proceed while the conflict in Ukraine rages on. As long as there is a chance that Russia could eventually contact them, it stands to reason that the leaders of Transnistria would not want to abandon their quest for independence. And even if they did, it would appear that Russia’s military presence on the ground would prevent them from doing anything disloyal to Moscow. However, if the conflict goes poorly for Russia, as it is now, things might start to change.

Moscow would not be able to aid Transnistria politically, militarily, or financially if such a scenario came to pass. It may be quite challenging to strike a settlement even at this point. If Transnistria appeared to be weakening, would Moldova be willing to offer a high level of autonomy or even a federal settlement?

Given all of this, some have argued that it could be more logical to embrace Transnistrian independence and simply let the issue go. States rarely cede land freely, therefore this is very unlikely. However, given that such discussions are common in separatist disputes, many Moldovans may consider it in secret. It would appear to have some advantages.

In addition to putting an end to a protracted debate, it would provide Moldova new alternatives, such as making joining the EU simpler. Although currently on the table due to Moldova’s constitutional pledge to neutrality, it might even pave the door for NATO membership. If both countries desired it, it might even make reunification with neighboring Romania possible, but it also comes with significant drawbacks.

It would be very difficult for Moldova to expel the nearly one-third of the Transnistrian population who are of Moldovan descent, unlike other ethnic disputes which are typically focused on specific ethnic groups. There are bigger geopolitical complications, which is more pertinent. An autonomous Transnistria might very possibly turn into another client state of Russia between Ukraine and Moldova, which would raise concerns. Transnistria would turn become another Russian exclave, similar to Kalinigrad between Poland and Lithuania, if it opted to join Russia. There is also the argument that Transnistria could establish closer ties with the West if it became independent, but this seems unlikely given Russia’s significant influence there.

Due to all of these factors and despite the current crisis in Ukraine, it is possible that Transnistria will just stay a frozen conflict. We may only witness a continuance of the existing quo, but in a new geopolitical framework of a very hostile relationship between Russia and the West, rather than a peaceful or violent resolution.

However, there seems to be a rising awareness that the outcome of the ongoing conflict in Ukraine could very well determine the future of Transnistria and of Moldova in general.

Bibliography

‘Assessing a Possible Moldova-Romania Unification | Geopolitical Monitor’. n.d. https://www.geopoliticalmonitor.com/assessing-a-possible-moldova-romania-unification/.

BBC News. 2022. ‘Transnistria and Ukraine Conflict: Is War Spreading?’, 27 April 2022, sec. Europe. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-61233095.

Bonner, Brian. 2022. ‘Moldova’s Future Is Tied to Russia’s War in Ukraine’. GIS Reports (blog). 4 October 2022. https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/moldova-russia-ukraine/.

Duffy, Martin. 2021. ‘Moldova and the Transnistria Conflict: Still a Regional Cold War?’ E-International Relations (blog). 3 August 2021. https://www.e-ir.info/2021/08/03/moldova-and-the-transnistria-conflict-still-a-regional-cold-war/.

‘EU Membership Obstacles for Ukraine, Moldova – DW – 06/18/2022’. n.d. Dw.Com. https://www.dw.com/en/what-hurdles-do-ukraine-and-moldova-face-on-the-path-to-eu-membership/a-62174986.

‘Moldova: Record-Breaking Support for Reunification with Romania’. 2021. OSW Centre for Eastern Studies. 19 April 2021. https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/analyses/2021-04-19/moldova-record-breaking-support-reunification-romania.

‘President Metsola: Moldova’s place is in Europe | Atualidade | Parlamento Europeu’. 2022. 11 November 2022. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/pt/press-room/20221111IPR53601/president-metsola-moldova-s-place-is-in-europe.

Radu, Sageata. 2015. ‘Romania. A Geopolitical Outline’. Potsdamer Geographische Forschungen, June, 45–58.

‘Romania-Moldova Unification Movement Grows Despite Obstacles’. 2018. Balkan Insight (blog). 4 September 2018. https://balkaninsight.com/2018/09/04/romania-moldova-unification-movement-grows-steadily-despite-obstacles-09-03-2018/.

Solovyov, Vladimir. n.d. ‘Ukraine War Risks Repercussions for Transnistria’. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/politika/87986.

‘Staying Neutral: Moldova’s PM Natalia Gavrilița Says Yes to Joining the EU but No to NATO’. 2022. Euronews. 8 March 2022. https://www.euronews.com/2022/03/08/staying-neutral-moldova-s-pm-natalia-gavrilita-says-yes-to-joining-eu-but-no-to-nato.

‘The “New” European Agenda of Moldova, the Unification with Romania and the Separation of the Transnistria Region. Analysis of Dionis Cenușa’. 2022. IPN. 5 April 2022. https://www.ipn.md/en/the-new-european-agenda-of-moldova-the-unification-with-romania-7978_1088960.html.

‘The Transnistrian Conflict: 30 Years Searching for a Settlement’. n.d. https://www.ui.se/forskning/centrum-for-osteuropastudier/sceeus-report/sceeus-report-no-4/.

‘Transnistria: The History Behind the Russian-Backed Region’. n.d. Origins. https://origins.osu.edu/read/transnistria-history-behind-russian-backed-region?language_content_entity=en.

‘Transnistria: The next Front of the Ukraine War | Lowy Institute’. n.d. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/transnistria-next-front-ukraine-war.