Written by Brian Fabrègue and Andrea Bogoni.

1. Introduction

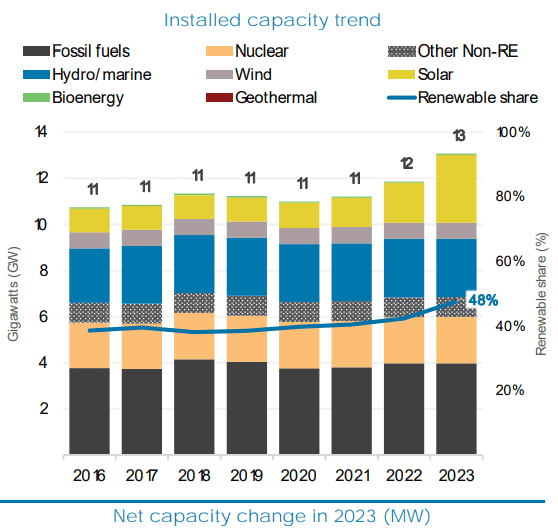

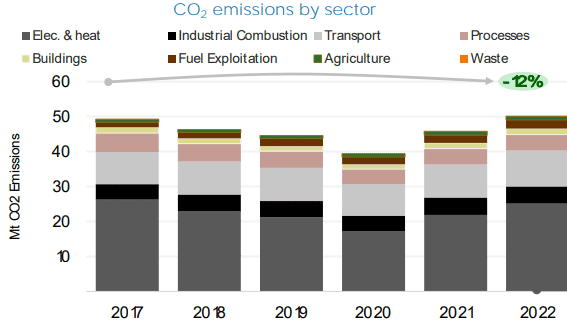

Bulgaria’s energy sector is at a critical juncture, with two main objectives shaping its direction: decarbonization and reducing reliance on Russian energy. Over the past year, Bulgaria has made considerable progress in expanding its renewable energy capacity, particularly in solar power. Solar energy production has surged from one gigawatt (GWh) in 2019 to more than three GWh today,[1] with solar accounting for nearly half of the country’s electric capacity from renewables.[2]

Bulgaria is also making strides in other renewable energy sources (RES), including wind, hydro, and bioenergy, while nuclear energy remains a significant part of the mix. In 2023, 66% of the country’s electricity came from non-fossil fuel sources, a figure expected to rise due to continued solar growth.[3] However, the decarbonization process, particularly in heavy industry, faces challenges. Industrial sectors still rely heavily on natural gas, and transitioning to electricity will require substantial investment.[4]

Moreover, nuclear energy continues to be a key part of Bulgaria’s energy landscape, contributing 23% of the country’s electricity production in 2023.[5] Plans from October 2023 to add two new reactors at the Kozloduy nuclear power plant (NPP) signal that nuclear will remain an essential energy source in the long term.[6] However, these new reactors won’t be operational for another decade at least, leaving Bulgaria with a pressing need to accelerate its decarbonization efforts with other sources.

Bulgaria is also playing a role in supporting Ukraine during its ongoing conflict with Russia. The country has been exporting electricity and fuel to Ukraine, and there are opportunities for deeper cooperation in the future, particularly in nuclear energy and renewables.[7] Negotiations are underway for Ukraine to purchase two Russian-made reactors from Bulgaria,[8] and post-war collaboration in offshore wind and solar energy in the Black Sea could further strengthen ties between the two nations.

2. Historical energy uncertainty

In the early 2000s, Bulgaria’s energy policy was characterized by a delicate balancing act between European aspirations and deep-rooted ties to Russia. Due to its strategic location in Southeast Europe (SEE), Bulgaria played a crucial role in various energy transit projects, particularly pipelines aimed at transporting natural gas. The country’s participation in both the Russian-backed South Stream pipeline and the EU-endorsed Nabucco project demonstrated this dual allegiance.[9] These projects represented competing visions for Europe’s energy future: while Nabucco aimed to reduce the continent’s dependency on Russian gas, South Stream was designed to reinforce Russia’s dominance in the region’s energy supply.

Bulgaria’s involvement in these projects was also shaped by its domestic politics. At the time, Bulgaria was governed by the Socialist Party, which traditionally had closer ties to Russia. This government sought to maintain good relations with Moscow, not only through pipeline projects but also by advancing nuclear energy cooperation. For example, Bulgaria agreed to collaborate with Russia on the construction of a new NPP at Belene. This plant, which would have used Russian technology, was seen by some as a symbol of Bulgaria’s ongoing dependence on Russian energy expertise and capital. However, the project faced numerous delays and financial difficulties, reflecting the complex nature of Bulgaria’s energy strategy at the time. It is now being repurposed to aid in the expansion of Kozloduy NPP.[10]

Under the leadership of Prime Minister Boyko Borisov, Bulgaria’s energy policy began to shift toward closer alignment with the European Union. Borisov’s government, which came to power in 2009, was more sceptical of Bulgaria’s heavy reliance on Russian energy. His administration expressed concerns over the financial and geopolitical implications of projects like South Stream and the Belene nuclear plant.[11] As a result, Bulgaria started to explore alternative energy options and sought to diversify its energy supply. This included increased interest in renewable energy sources, as well as efforts to strengthen its energy ties with the EU.

Despite these efforts to move closer to Europe, Bulgaria continued to face challenges in reducing its dependency on Russian energy. Financial constraints also played a major role in Bulgaria’s energy policy. The costs of maintaining and upgrading energy infrastructure, particularly in the nuclear sector, were substantial. The Belene nuclear plant, for instance, faced ballooning costs, which eventually led to the project being frozen by Borisov’s government in 2012 amidst Russian claims of alleged U.S. influence.[12] Similarly, the South Stream pipeline was officially cancelled in 2014, after facing opposition from the European Union due to concerns over Russia’s influence in the region and issues related to EU energy regulations.[13]

With regards to renewables, in 2007, Bulgaria’s green energy sector seemed full of potential as the country joined the European Union. Incentivized by EU directives and a favourable investment climate, the Bulgarian government introduced legislation offering generous subsidies, including preferential pricing and long-term contracts for renewable energy. Despite the lack of a clear strategy at the central level, the sector experienced a fast-paced development, especially for wind farms and solar energy (and, to a lesser extent, for new hydroelectric power plants).

By 2012, Bulgaria had reached significant milestones, becoming a regional leader in SEE for renewables, with installed capacity exceeding 2.2 GWh.[14] Over 4 billion Euros were invested from 2009 to 2012; with over 1,900 active companies, with at least 10,000 employees. The boom in renewable sources allowed Bulgaria to reach the share of green energy on the total consumed, fixed by the EU at 16% by 2020, eight years in advance.

However, the rapid expansion came at a cost. The state’s subsidy policies caused a significant increase in electricity prices, leading to public dissatisfaction and protests. In 2013, these “crazy bills” protests forced the government to resign.[15] As Bulgaria sought to curb rising costs, the government reduced subsidies, imposed a moratorium on new installations, and attempted to implement retroactive taxes on renewable energy producers. This shift from initial over-permissiveness to a more restrictive approach has created uncertainty in the sector, leading to concerns about its long-term sustainability.

3. Outlook of the energy sector

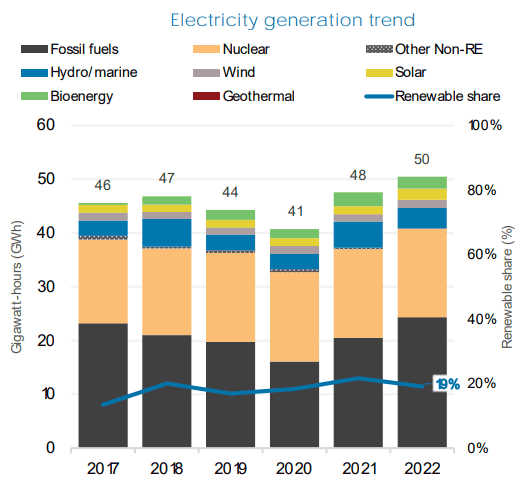

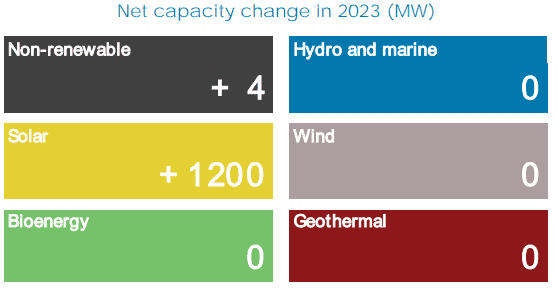

Bulgaria’s power sector is still undergoing significant changes, balancing its traditional reliance on coal power with an increasing shift toward renewable energy. As shown in the chart below, in 2022, the country saw a 5.7% growth in electricity production, driven largely by renewable sources like photovoltaics – which expanded by 33% due to new capacities and favourable weather – and increased use of coal to produce electricity. Considering the costs of the green transition and Bulgaria’s role as an exporter to other SEE countries diverging from Russian sources, the latter measure is understandable in the short-term.

Source: IRENA

Bulgaria’s National Energy and Climate Plan[16] emphasizes increasing the share of renewable energy in its energy mix. As also specified in the draft updated plan, it aims for a 27% share of renewables in its gross final energy consumption by 2030 and includes specific targets such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 49% in the non-ETS sectors compared to 2005 levels and improving energy efficiency by 27.89%.[17] Bulgaria also aims to increase interconnectivity with other European countries and plans to modernize its energy infrastructure to support the integration of renewable energy sources like wind, solar, and biomass.

The European Commission’s opinion on Bulgaria’s National Energy and Climate Plan stresses several key areas where the country needs to improve in order to align with EU climate goals, particularly those set under the European Green Deal. While Bulgaria sets several targets for its renewable energy sources, the Commission suggests this may not be ambitious enough, given the broader EU targets for decarbonization and renewable energy. It is also noted that while Bulgaria’s energy mix is transitioning, coal and nuclear still dominate the country’s power generation, which could hinder progress toward achieving a more diversified and cleaner energy portfolio.[18]

The Commission encourages Bulgaria to accelerate its investments in renewable energy and also highlights the need for Bulgaria to improve the overall energy efficiency of its infrastructure. Another major point of emphasis from the European Commission is the need for Bulgaria to strengthen its grid infrastructure and connectivity with neighbouring countries to accommodate increased renewable energy generation. Greater interconnectivity between Bulgaria and other EU countries could bolster energy security, which is especially crucial given the country’s historical reliance on imported fossil fuels. Positively, last year’s joint plan with Romania to build a hydropower on the Danube goes in this direction.[19] In terms of greenhouse gas the Commission’s assessment notes that this target is a step in the right direction, but given the country’s reliance on domestic lignite it suggests that Bulgaria should increase its ambition to ensure consistency with the EU-wide objective of climate neutrality by 2050.

Coal

Coal remains a cornerstone of Bulgaria’s energy production, contributing around 40% to its electricity generation as of 2022.[20] The country has vast coal reserves, totalling 4.8 billion tons, with lignite making up 92% of this.[21] Lignite is a low-grade but widely used form of coal for electricity generation, and Bulgaria’s Maritsa Iztok basin, containing nearly 3 billion tons of lignite, powers the largest energy complex in SEE. Other lignite basins include those in the Sofia Valley, Elhovo, Lom, and Maritsa Zapad, while smaller sub-bituminous coal reserves are concentrated in Bobov Dol, Pernik, and Burgas.

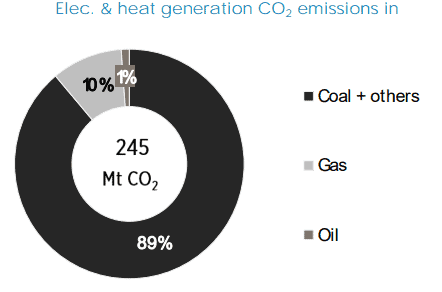

In 2022, Bulgaria produced 36 million tons of coal, with 98% being lignite. The Maritsa Iztok mines alone accounted for 98.6% of the lignite extracted. About 97% of the coal produced is used for electricity and thermal power generation, while 2% is used to produce briquettes.[22] The production of electricity through coal is the country’s heaviest polluter.

Source: IRENA

Despite its reliance on coal, Bulgaria has committed to gradually phasing out coal production, aiming to reduce its use by 2030 and fully discontinue coal as an energy source by 2038.[23] To support this transition, the European Union has allocated €1.2 billion to help Bulgaria achieve a just transition. This funding is intended to mitigate the socioeconomic impacts of the coal phase-out, particularly in coal-dependent regions such as Stara Zagora, where the Maritsa Iztok complex is located.

In addition to lignite, Bulgaria has smaller reserves of sub-bituminous coal and a large, but currently unexploited, basin of bituminous coal in Southern Dobruja. The bituminous coal reserves in Dobruja are estimated to exceed 1 billion tons, but the significant depth at which they are located, between 1,370 and 1,950 meters, makes commercial extraction challenging.[24]

Nuclear

Bulgaria’s nuclear power sector is undergoing significant expansion, with the government setting ambitious goals to enhance energy capacity. Kozloduy NPP remains central to the country’s energy sector, producing about 35% of its electricity and granting around a quarter of its total energy supply.[25] Located near the Danube River. It originally operated six units, with four VVER-440 reactors decommissioned in the early 2000s as part of Bulgaria’s EU accession process (units 1-4). Today, Kozloduy operates two VVER-1000 reactors, units 5 and 6, which generate around 34% of Bulgaria’s electricity. Both units have undergone upgrades to extend their operational lifespan to 60 years.

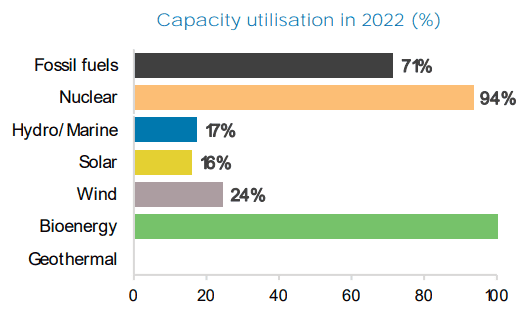

As shown in the chart below, the capacity utilisation of the NPP is at 94%. To increase the overall potential of the plant, the government planned in 2023 to add two more reactors utilizing Westinghouse AP1000 technology (units 7 and 8).[26]

Source: IRENA

The two new Westinghouse AP1000 reactors planned for the Kozloduy NPP are expected to significantly boost the country’s energy production, aiming for a combined capacity of 2300 MWe. This will surpass the 1760 MWe capacity of the previously closed Kozloduy units 1-4. The target for the first unit’s completion is 2033, with the second unit to follow within two to three years.

The AP1000 technology, known for its advanced safety and modular construction, is part of Bulgaria’s middle-term and long-term strategy to diversify its energy mix and move away from dependence on older VVER-440 models.

Bulgaria’s Ministry of Energy has outlined a transparent selection process for contractors, ensuring that companies must meet strict criteria, including the successful construction and commissioning of nuclear units and a minimum financial turnover of USD 6 billion over five years.[27] Russian companies have been explicitly excluded from the bidding process, reflecting Bulgaria’s shift toward Western technology and energy diversification following geopolitical tensions.

Efforts to diversify nuclear fuel supply have also led Kozloduy NPP to sign a deal with Westinghouse Electric for Unit 5, switching from Russian to non-Russian fuel in mid-2024.[28] These developments signal Bulgaria’s intention to maintain nuclear energy as a key part of its energy mix while reducing dependence on Russian sources. The 2016 settlement with Russia over the cancelled Belene plant project and subsequent storage of equipment at the site also play into the nation’s ongoing nuclear strategy.

Renewables

Moscow’s decision to cut gas exports to Bulgaria after the invasion of Ukraine spurred a shift towards renewable energy and energy efficiency investments in the country. Bulgaria aims for 27% RES by 2030, but significant funding is needed to replace coal with photovoltaics, wind, biomass, and geothermal energy.[29]

Source: IRENA

Bulgaria’s solar power potential is significant, especially in the southern regions. The country has rapidly expanded its solar capacity from 100 MW in 2011 to over 2,400 MW by 2023, with 600 MW added in 2022 alone.[30] The largest solar parks are Dalgo Pole (207 MW) and Verila (123 MW). Solar energy is also increasingly being adopted by companies and households to reduce grid dependence. In May 2023, for the first time, solar energy briefly surpassed nuclear and thermal power, producing 31% of the nation’s electricity.[31] Bulgaria is on track to surpass its 2030 renewable energy targets, but investments in modernization are crucial to ensuring that new wind and solar projects are efficiently connected to the grid. Bulgaria is also pushing for small- and medium-sized businesses to adopt more self-sustaining energy solutions, including solar energy and battery storage, to reduce dependency on the grid during peak consumption times.

Source: IRENA

In terms of wind power, Bulgaria had 708 MW of installed capacity in 2019, with the potential to reach up to 3.4 GW.[32] Hydropower, another key resource, generates over 10% of Bulgaria’s electricity. The majority of hydropower plants are owned by NEK EAD and located in the Rhodope and Rila Mountains, with a total installed capacity of 2,737 MW. These plants are organized into major hydropower cascades, such as the Belmeken–Sestrimo–Chaira (1,599 MW) and Dospat–Vacha (500 MW) systems. The Chaira Pumped Storage Hydropower Plant, the largest in SEE, plays a crucial role in balancing grid demands.

Source: IRENA

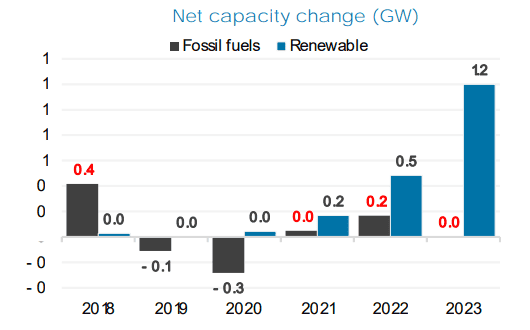

Bulgaria’s national strategy aims to drastically reduce the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions, but parliamentary decisions to retain coal plants until 2038 complicate these efforts. The government’s 2023 decision to keep coal plants online could potentially risk €1 billion in EU modernization funds.[33] While the country’s efforts to diversify, transition and export to neighbouring countries affected by the cut in Russian sources are notable, a long-term strategy should be envisioned. The combination of RES, nuclear power, and improved energy efficiency could stabilize Bulgaria’s electricity prices and ensure energy security in the long run.

Oil and gas

Bulgaria’s natural gas market has undergone significant changes following Gazprom’s decision to cut off supplies in April 2022,[34] after the country refused to comply with the demand to pay for gas in rubles. In response, Bulgaria secured alternative supplies from Azerbaijan and the United States. The country, which also transports Russian gas to Serbia and Hungary via the TurkStream pipeline,[35] can transmit over 20 billion cubic meters (bcm) of gas annually through its network to Europe.

This pipeline, which carries gas from a mix of sources – of which Russian gas is believed to account for 40% of the total[36] – through Turkey and into SEE, was designed to bypass Ukraine, a major transit country for Russian gas, and reduce its importance in the European energy supply chain. Despite European Union sanctions imposed after Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and its subsequent actions in Ukraine, projects like TurkStream show how Russia continues to find ways to sidestep Western attempts at energy diversification. Gazprom, Russia’s state-owned gas company, has consistently sought to increase its control over European energy markets, and the TurkStream project is a prime example of this broader strategy.

Attempting to diversify its supply, one of Bulgaria’s major recent infrastructure projects is the 182-km Interconnector Greece-Bulgaria (IGB). Operational as of early 2023, the IGB is expanding its capacity to over 5 bcm annually to increase gas imports from Greece’s LNG terminals and the Southern Gas Corridor. The now operational Alexandroupolis LNG terminal, will play a key role in enhancing Bulgaria’s energy security.[37] Additionally, a new gas interconnection with Serbia (Interconnector Bulgaria-Serbia/IBS) that we have previously talked about, began construction in February 2023, enhancing the region’s energy connectivity with an expected capacity of 1.8 bcm per year. The IBS is co-funded by the EU under the Connecting Europe Facility. Bulgaria is also exploring hydrogen pipeline opportunities with Greece[38] and launched an oil and gas exploration in the Black Sea in 2023. This exploration is part of the country’s broader strategy to diversify energy supplies and reduce dependency on Russian resources, while increasing its reach in the Black Sea.

Nevertheless, in the oil sector, Bulgaria remains a major buyer of Russian crude oil, particularly for the Lukoil Neftochim refinery in Burgas, which is the largest in the Balkans.[39] However, Bulgaria is taking steps to secure alternative oil supplies. In early 2023, the Bulgarian government revived plans for a trans-Balkan oil pipeline that would transport non-Russian crude oil from the Greek port of Alexandroupolis to Burgas.[40] This pipeline is intended to ensure a steady supply of crude oil.

With substantial energy investments and infrastructure upgrades, Bulgaria is gradually positioning itself as a major energy hub in SEE.

Electricity

Bulgaria remains the most energy-intensive economy in the EU, using 3.5 times more energy per GDP unit than the EU average, largely due to its reliance on coal and nuclear power.[41] The energy sector is the country’s biggest greenhouse gas polluter, responsible for more than half of emissions. Despite a commitment to decarbonize by 2050, Bulgaria plans to keep using domestic lignite.

Source: IRENA

Bulgaria has struggled with its energy efficiency obligation scheme, but new projects, such as smart meters, digital transformation, and electric vehicle charging stations, are expected to improve the energy sector’s efficiency and integration of renewable energy sources. EUR 196 million in EU funding will be used to modernize Bulgaria’s electricity grid, particularly in Southeastern Bulgaria, by supporting the digitalization of energy systems and improving data management from smart meters.[42] These efforts are crucial as Bulgaria seeks to improve energy efficiency, integrate renewables, and transition away from fossil fuels.

Bulgaria’s electricity generation in fact heavily depends on coal and nuclear energy, with coal historically providing around half of the country’s electricity and nuclear about 35%. Renewable energy sources, led by large hydropower, also contribute, while biofuels play a larger role than solar and wind. Despite being a net electricity exporter, with major buyers like Romania, Greece, and North Macedonia, Bulgaria’s energy strategy remains fossil-fuel dependent. The 2019 National Energy and Climate Plan indicated a long-term reliance on coal and nuclear, with no immediate phase-out in sight.[43]

4. Future prospects

As Russia’s invasion of Ukraine sent shock waves across Europe, SEE is bracing to bear the brunt of the economic, financial, and security consequences. The region is heavily reliant on Russian gas and oil, and for regular supply Russia is a major trading partner and investor. The sanctions on Russia and the indirect consequences of higher energy and raw material prices and supply chain disruptions have impacted businesses across the board, curbing production, further fuelling inflation and slowing recovery.

In 2023, Bulgaria – which still bases much of its energy production on coal – was the only EU country that had not presented a clear action plan on how to make the transition.[44] Despite EU warnings, more than a year later, progress has been made towards RES, but the situation in the Bulgarian energy sector retains many critical elements. Various factors contribute to slowing and hindering the process.

On the one hand, the very strong political instability in which Bulgaria has found itself navigating in recent years: since 2021, the country has faced no fewer than six general elections, all of which resulted in parliaments incapable of creating stable political majorities.[45] The last attempt in May 2024 also failed, and voters were called to the polls again on 26 October.

At the same time, there is a lot of resistance and concern about the impact on employment, with thousands of workers fearing a future of uncertainty and unemployment, especially in areas where coal mining is central to the local economy, such as Stara Zagora, Pernik and Kyustendil.[46] In September 2023, the miners had staged strikes and protests against the executive’s draft operational plan for the transition, which then resulted in a seven-point agreement signed by the government and professional organisations.

The energy situation in Bulgaria – the country with the lowest GDP per capita in Europe – remains critical, but has shown signs of dynamic resilience. It has gradually moved from historical dependence on Russian sources to becoming an exporter of electricity to neighbouring countries in South-Eastern Europe and Ukraine. In recent years, with the help of the European Community, Bulgaria has invested in key infrastructure projects with partners such as Greece, Romania and Serbia, which will benefit its energy mix in the long term.

The recent surge in solar energy capacity is also a sign of the country’s transition to renewable energy, but sustainability cannot be achieved in the short term and without high costs. Addressing the use of coal for power generation – a major C02 emitter – is urgent, but certainly a process that must be implemented gradually. Drastic measures could aggravate an already critical situation, with social, economic and geopolitical consequences that would ultimately damage Europe’s southern flank and potentially strengthen Russia’s grip on the region.

In this context, nuclear power, which has reached near-maximum capacity and is currently being expanded, could be seen as a medium-term enabler of a just transition. Coupled with new fuel sourcing, it would provide a stable energy stream – as well as an opportunity to convert coal mining jobs, increasing Bulgaria’s overall security and ability to continue its transition to a net-carbon economy.

References

- Solar Power Europe, ‘Eastern Europe’s Solar Surge: Spotlight on Bulgaria, Romania, and Czechia’, SolarPower Europe, n.d., https://solarpowereurope.org/features/eastern-europe-s-solar-surge-spotlight-on-bulgaria-romania-and-czechia. ↑

- International Renewable Energy Agency, ‘Bulgaria Energy Profile’ (IRENA, 2024), https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Statistics/Statistical_Profiles/Europe/Bulgaria_Europe_RE_SP.pdf. ↑

- Francesco Martino, ‘Energy in Bulgaria, between past and future’, Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso, 30 September 2024, https://www.balcanicaucaso.org/eng/Areas/Bulgaria/Energy-in-Bulgaria-between-past-and-future-233520. ↑

- International Renewable Energy Agency, ‘Bulgaria Energy Profile’. ↑

- International Renewable Energy Agency. ↑

- Editorial Staff, ‘Bulgaria to Begin Work on Two Reactors at Kozloduy Nuclear Site’, Reuters, 25 October 2023, sec. Europe, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/bulgaria-begin-work-two-reactors-kozloduy-nuclear-site-2023-10-25/. ↑

- Philip Volkmann-Schluck, ‘Bulgaria to the Rescue: How the EU’s Poorest Country Secretly Saved Ukraine’, POLITICO, 18 January 2023, https://www.politico.eu/article/bulgaria-volodymyr-zelenskyy-kiril-petkov-poorest-country-eu-ukraine/. ↑

- Pavel Polityuk, ‘Exclusive: Ukraine Hopes to Start Installing Nuclear Reactors from Bulgaria in June’, Reuters, 22 March 2024, sec. Energy, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/ukraine-hopes-start-installing-nuclear-reactors-bulgaria-june-2024-03-22/. ↑

- Pavel K. Baev and Indra Øverland, ‘The South Stream versus Nabucco Pipeline Race: Geopolitical and Economic (Ir)Rationales and Political Stakes in Mega-Projects’, International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-) 86, no. 5 (2010): 1075–90. ↑

- Honney Tracey, ‘Bulgaria to Repurpose Equipment from Cancelled Belene Project for Kozloduy Expansion’, Nuclear Engineering International (blog), 29 May 2024, https://www.neimagazine.com/news/new-build-life-extension/bulgaria-to-repurpose-equipment-from-cancelled-belene-project-for-kozloduy-expansion/. ↑

- Dobrin Kanev, ‘Political Change in Bulgaria: Interpreting the 2009 General Election Results’, SEER: Journal for Labour and Social Affairs in Eastern Europe 13, no. 1 (2010): 41–54. ↑

- Editorial Staff, ‘Russian Newspaper Falsely Claims U.S. Pressed Bulgaria to Quit the Belene Nuclear Power Plant’, Voice of America, 29 August 2019, https://www.voanews.com/a/russian-newspaper-false-claims-belene-nuclear-power-fact-check/6742217.html. ↑

- Antto Vihma and Umut Turksen, ‘The Geoeconomics of the South Stream Pipeline Project’, Columbia University, Journal of International Affairs (blog), 1 January 2016, https://jia.sipa.columbia.edu/news/geoeconomics-south-stream-pipeline-project. ↑

- Francesco Martino, ‘Green energy in Bulgaria: an uneasy success’, Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso, n.d., https://www.balcanicaucaso.org/eng/Areas/Bulgaria/Green-energy-in-Bulgaria-an-uneasy-success-158848. ↑

- Otilia Simkova, ‘Bulgaria: Political Turmoil Could Hit Energy Investors’, 21 February 2013, https://www.ft.com/content/ca446ad4-a4c7-3268-abc6-b71d7abf2c27. ↑

- Ministry of Energy and Ministry of the Environment and Water, ‘Integrated Energy and Climate Plan of the Republic of Bulgaria 2021-2030’ (Republic of Bulgaria, n.d.), 2021–30, https://energy.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2020-06/bg_final_necp_main_en_0.pdf. ↑

- European Commission, ‘Bulgaria’s Draft Updated National Energy and Climate Plan’, 2024, https://commission.europa.eu/document/download/fbf19cd3-a8c6-4fcc-887f-48f8dda8b1d6_en?filename=Factsheet_Commissions_assessment_NECP_%20Bulgaria_2024.pdf.pdf&prefLang=bg. ↑

- European Commission, ‘Summary of the Commission Assessment of the Draft National Energy and Climate Plan 2021-2030’, 2024, 2021–30, https://energy.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2019-06/necp_factsheet_bg_final_0.pdf. ↑

- Madalin Necsutu, ‘Romania, Bulgaria to Build Two Hydropower Plants on Danube’, Balkan Insight (blog), 18 January 2023, https://balkaninsight.com/2023/01/18/romania-bulgaria-to-build-two-hydropower-plants-on-danube/. ↑

- International Renewable Energy Agency, ‘Bulgaria Energy Profile’. ↑

- EURACOAL, ‘Bulgaria’, The Voice of Coal in Europe (blog), 4 February 2024, https://euracoal.eu/info/country-profiles/bulgaria-8/. ↑

- EURACOAL. ↑

- Kate Abnett, ‘Market Economics to Cut Bulgaria’s Coal Use before 2038 Deadline – Minister’, Reuters, 15 January 2024, sec. Climate & Energy, https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/climate-energy/market-economics-cut-bulgarias-coal-use-before-2038-deadline-minister-2024-01-15/. ↑

- EURACOAL, ‘Bulgaria’. ↑

- International Renewable Energy Agency, ‘Bulgaria Energy Profile’. ↑

- Editorial Staff, ‘Bulgaria to Push Ahead with Two New Units at Kozloduy’, World Nuclear News, n.d., https://world-nuclear-news.org/articles/bulgaria-to-push-ahead-with-two-new-units-at-kozlo. ↑

- Editorial Staff, ‘Five Express Interest in Kozloduy New Nuclear Construction’, World Nuclear News, n.d., https://world-nuclear-news.org/articles/five-express-interest-in-kozlody-new-nuclear-const. ↑

- Intern Editor, ‘Westinghouse To Supply Nuclear Fuel For Kozloduy NPP From 2024’, ENS (blog), 28 December 2022, https://www.euronuclear.org/news/westinghouse-to-supply-nuclear-fuel-for-kozloduy-npp-from-2024/. ↑

- Luciana Miu, ‘Assessment of Bulgaria’s Long-Term Strategy for Climate Neutrality’ (Bucharest: Energy Policy Group, 8 December 2022), https://climatedialogue.eu/sites/default/files/2022-12/Report_Assessment_of_Bulgarias_Long-Term_Strategy.pdf. ↑

- Igor Todorović, ‘Bulgaria Enjoys Solar Boom as Biggest Photovoltaic Parks Come Online’, Balkan Green Energy News, 31 August 2023, https://balkangreenenergynews.com/bulgaria-enjoys-solar-boom-as-biggest-photovoltaic-parks-come-online/. ↑

- Bulgaria National Radio, ‘Solar Parks Provide More than 31% of Electricity Production in Bulgaria’, n.d., https://bnr.bg/en/post/101834797. ↑

- REVE, ‘The Growing Importance of Wind Power in Bulgaria’, 25 June 2023, https://www.evwind.es/2023/06/25/the-growing-importance-of-wind-power-in-bulgaria/92440. ↑

- Emiliya Milcheva and Krassen Nikolov, ‘Bulgaria Risks Losing Billions in Recovery Money as Parliamentary Chaos Ensues’, www.euractiv.com, 30 September 2024, https://www.euractiv.com/section/politics/news/bulgaria-risks-losing-billions-in-recovery-money-as-parliamentary-chaos-ensues/. ↑

- Editorial Staff, ‘Gazprom Informs Bulgaria It Will Halt Gas Supplies as of April 27’, Reuters, 26 April 2022, sec. Energy, 27, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/gazprom-informs-bulgaria-it-will-halt-gas-supplies-april-27-2022-04-26/. ↑

- Editorial Staff, ‘Gazprom Ramps up Gas Flows to Hungary via Turkstream Pipeline, Official Says’, Reuters, 13 August 2022, sec. Energy, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/gazprom-ramps-up-gas-flows-hungary-via-turkstream-pipeline-official-says-2022-08-13/. ↑

- Martin Vladimirov, ‘Closing the Backdoor: The New TurkStream Is Here. Can the West Stop It?’, POLITICO, 30 August 2024, https://www.politico.eu/article/turkstream-putin-erdogan-gas-pipeline-gazprom-eu-sanctions/. ↑

- Igor Todorović, ‘Alexandroupolis LNG Terminal Begins Commercial Operations’, Balkan Green Energy News, 1 October 2024, https://balkangreenenergynews.com/alexandroupolis-lng-terminal-begins-commercial-operations/. ↑

- ICGB, ‘ICGB Sees Future Potential for Hydrogen to Flow along Greece-Bulgaria Gas Pipeline’, Renewablesnow.com, n.d., https://renewablesnow.com/news/icgb-sees-future-potential-for-hydrogen-to-flow-along-greece-bulgaria-gas-pipeline-822879/. ↑

- Victor Jack, ‘Russian Oil Titan Lukoil Eyes the End of Its Reign in Bulgaria’, POLITICO, 21 August 2023, https://www.politico.eu/article/bulgaria-struggle-escape-grip-of-russia-lukoil-oil-company-eu-sanction/. ↑

- Editorial Staff, ‘Bulgaria Seeks to Revive Trans-Balkan Pipeline Project to Secure Non-Russian Oil’, Reuters, 17 January 2023, sec. Energy, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/bulgaria-seeks-revive-trans-balkan-pipeline-project-secure-non-russian-oil-2023-01-17/. ↑

- Luciana Miu, ‘Assessment of Bulgaria’s Long-Term Strategy for Climate Neutrality’. ↑

- Inforegio, ‘EU Supports Just Climate Transition in Bulgaria with a Budget of €1.2 Billion’, European Commission, 21 December 2023, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/whats-new/newsroom/21-12-2023-eu-supports-just-climate-transition-in-bulgaria-with-a-budget-of-eur1-2-billion_en. ↑

- Luciana Miu, ‘Assessment of Bulgaria’s Long-Term Strategy for Climate Neutrality’. ↑

- Victor Jack, ‘Bulgaria’s Miners Face Dark Future with Millions of EU Funds in Jeopardy’, POLITICO, 29 June 2023, https://www.politico.eu/article/bulgaria-europe-miner-coal-dark-future-with-millions-of-eu-funds-jeapordy/. ↑

- Csongor Körömi, ‘Groundhog Vote: After 6 General Elections in 3 Years, Bulgaria Heads to Polls for Seventh Time’, POLITICO, 5 August 2024, https://www.politico.eu/article/six-general-elections-three-years-bulgaria-polls/. ↑

- Jack, ‘Bulgaria’s Miners Face Dark Future with Millions of EU Funds in Jeopardy’. ↑