Introduction and Global Scenario

Precious metals are most often associated with the jewellery industry or speculative investments, but in the case of silver, this is only the tip of the iceberg. Its properties – the highest thermal and electrical conductivity of all metals, antibacterial properties, elasticity and high light reflectivity – mean that silver has a wide range of applications in industry, medicine and even cosmetology[1].

Given these characteristics, silver is one of the most important materials needed for the production of photovoltaic panels, digital infrastructure (including 5G networks, for example), batteries, electric cars, semiconductors or sterile medical equipment[2]. Clearly, this refers to most of the sectors associated with the ambitious goals of decarbonising and digitalising economies.

Currently, global silver demand has remained relatively stable since 2010, oscillating around 30,000 to 35,000 tonnes per year[3]. However, with European Union countries, the United States and Japan (as well as China and India by 2070) planning to achieve climate neutrality by 2050, it is anticipated that global silver demand could increase to as much as 80,000 tonnes per year by 2030[4]. As demand intensifies, it is likely that the price of this commodity will increase in the future, having stabilised at USD 20-25 per ounce for several years[5]. This will mean an increase in profitability and, consequently, in the volume of its extraction, which currently remains stable since many years – amounting to 26,000 tonnes in 2022.

In this context, extremely positive information can be read in the latest “Mineral Commodity Summaries 2024” report, issued by the United States Geological Survey (USGS). It appears that out of all the silver deposits identified so far worldwide (720 thousand tonnes), as much as 170 thousand tonnes, i.e. almost 25%, can be found in Poland[6]. These are the largest deposits of all countries in the world, and the only ones in Europe – not counting Russia, with which, however, most trade relations have been severed. The value of the Polish deposits is estimated at USD 127 billion – it should be remembered, however, that in the event of a surge in global demand this will also translate into higher silver prices, increasing the aforementioned amount.

Polish Silver Resources

To date, Poland has mined negligible amounts of silver – for several years it has amounted to around 1 300 tonnes, i.e. around 5% of world output[7]. It can therefore be observed that despite the huge resources, Poland is not yet fully exploiting the potential of its silver deposits. An important goal for the current decade should therefore be to utilise them wisely and not predatorily. Increasing silver mining and exports might seem a natural response, but in this case the Polish economy would get rid of most of the potential added value associated with further processing of the raw material.

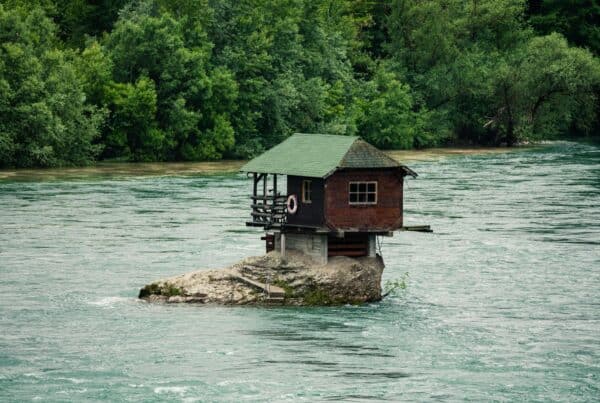

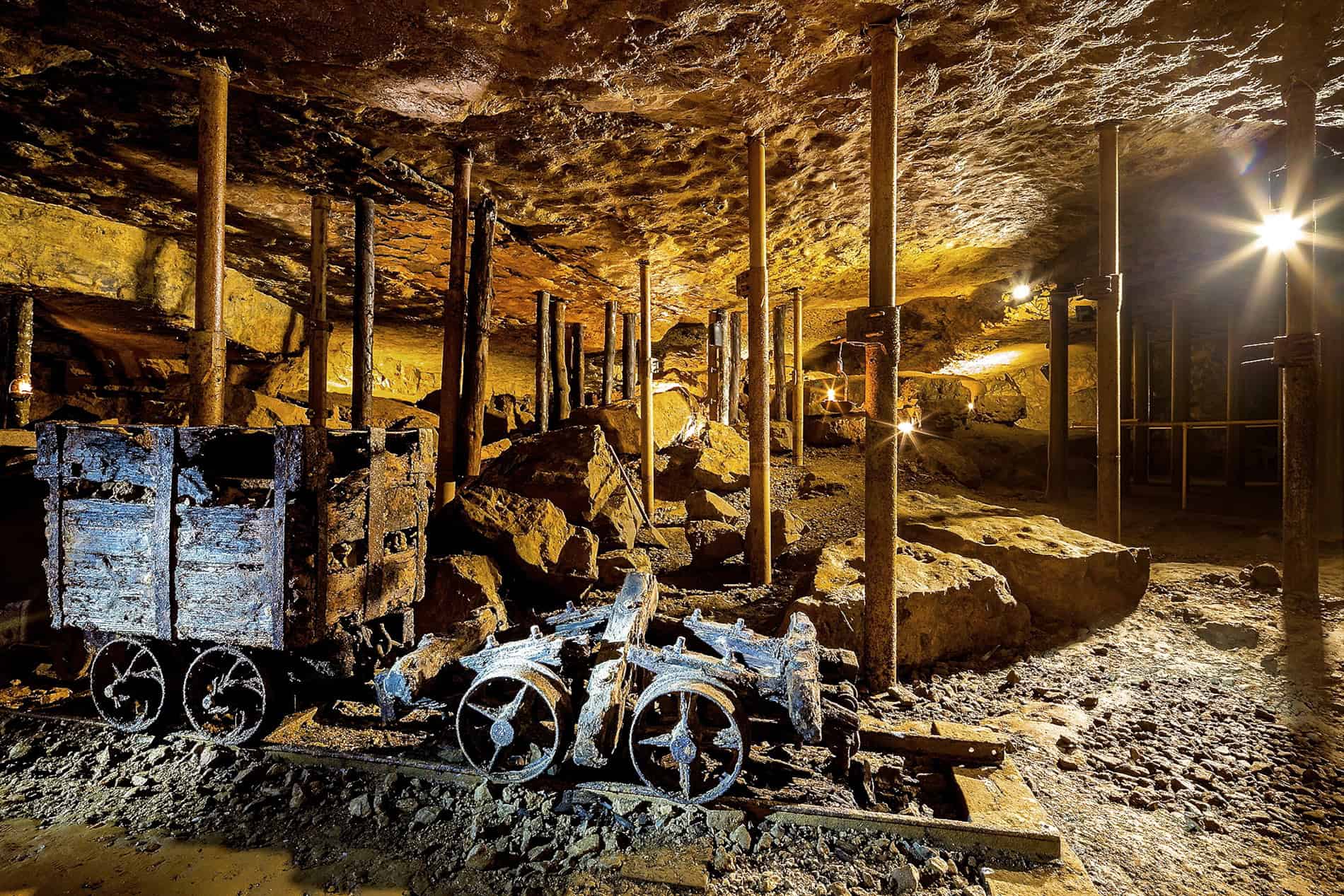

Tarnowskie Gory Lead-Silver-Zinc Mine and its underground water management system, added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in July 2017.

Polish decision-makers should therefore foster the development of sectors that support the decarbonisation and digitalisation of economies, which, because of silver the deposits, will have the necessary raw material supply. Some of the most notable directions include photovoltaic panels, digital infrastructure and electric cars.

The photovoltaic market has already become one of the pillars of the Polish economy, experiencing 61% growth in 2022 and reaching a capacity of 12.4 GW coming from more than 1.2 million installed panels. As Ireneusz Zyska, Government Representative for Renewable Energy Sources, notes, “Our ambition is to take a leading position in the development of photovoltaics in Europe in the coming years. And it is not only about year-on-year growth in installed capacity, but first and foremost about building a photovoltaic industry based on innovative Polish technologies, whose products will win customers in domestic and foreign markets.” This will undoubtedly be much easier to do with the aforementioned silver deposits[8].

The expansion of digital infrastructure may also become an important way to make wise use of the silver deposits at hand. According to the DigitalPoland report, Poland is slightly underperforming in terms of ICT investments and connectedness (90% and 87% of the CEE average, respectively), which means that it needs to be further developed by investing in solutions such as 5G or broadband internet network[9].

With the decline in demand for internal combustion cars caused, among other things, by the EU’s ban on the registration of new cars from 2035, the automotive industry is being forced to look for new solutions. One possible direction is the transformation towards electromobility. However, the experience of the Polish automotive industry in the sphere of electric cars is so far limited. At present, only three models of electric cars are manufactured in Poland (Jeep Avenger, Fiat 600e and Fiat e-Ducato). However, no C-class electric cars are being built. For years, there has been a discussion about a project to build a large factory of domestic electric cars (under the Izera brand), which, according to Tomasz Kędzierski, strategy director at ElectroMobility Poland, which could become “a catalyst for our entire automotive market“[10]. It is therefore yet another industry, that could benefit from the utilisation of the aforementioned resources.

To date, the development of the mentioned industries has been limited by strong competition from China, but in the face of the European “de-risking” of supply chains[11], it would be worthwhile to nurture local production, thus joining the key players in the European Union.

References

- G. Chandrashekhar, Silver set to become a precious industrial metal, “BusinessLine”. 17.01.2022, https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/markets/commodities/silver-set-to-become-a-precious-industrial-metal/article64906616.ece [accessed: 26.03.2024]. ↑

- E. Harp, Silver is the Key to the Green Revolution, “VettaFi”, 17.08.2021, https://etfdb.com/gold-silver-investing-channel/silver-is-the-key-to-the-green-revolution/ [accessed: 26.03.2024]. ↑

- Statista, Demand for silver worldwide from 2010 to 2022, with a forecast for 2023 (in million ounces), „Statista”, 30.10.2023, https://www.statista.com/statistics/1240917/global-silver-demand/ [accessed: 25.03.2024]. ↑

- J. Chester, Copper and Silver Demand Set to Surge Amid Supply Deficits, “Crux Investor”, 03.10.2023, https://www.cruxinvestor.com/posts/copper-and-silver-demand-set-to-surge-amid-supply-deficits [accessed: 25.03.2024]. ↑

- Bankier.pl, Silver prices, https://www.bankier.pl/inwestowanie/profile/quote.html?symbol=SREBRO [accessed: 16.03.2024]. ↑

- United States Geological Survey, Mineral Commodity Summaries 2024, Virginia 2024, p. 162-164. ↑

- Business Insider, Huge bullion deposits in Poland. American report: Poland ranks first in the world, “Business Insider”, 24.02.2024, https://businessinsider.com.pl/gospodarka/odkryto-ogromne-zloza-amerykanski-raport-polska-ma-je-najwieksze-na-swiecie/fw6d12s [accessed: 26.03.2024]. ↑

- Agencja Rynku Energii, Photovoltaic market in Poland – new report from the Institute of Renewable Energy, 02.06.2023, https://www.are.waw.pl/o-are/aktualnosci/rynek-fotowoltaiki-w-polsce-nowy-raport-instytutu-energetyki-odnawialnej [accessed: 26.03.2024]. ↑

- M. Szutiak, Digitisation of public services: Poland compares well with the region, “Telepolis”, 07.09.2022, https://www.telepolis.pl/wiadomosci/prawo-finanse-statystyki/polska-cyfryzacja-uslug-publicznych-raport-2022 [accessed: 26.03.2024]. ↑

- N. Chinowski, Electromobility. Why is Poland losing the competition for large investments to other countries?, “Forsal”, 19.02.2024, https://forsal.pl/transport/aktualnosci/artykuly/9435642,elektromobilnosc-dlaczego-polska-przegrywa-rywalizacje-o-duze-inwestycje-z-innymi-krajami.html [accessed: 26.03.2024]. ↑

- M. Przychodniak, EU Trying to Reduce Dependence on China, “The Polish Institute of Foreign Affairs”, 29.02.2024, https://pism.pl/publications/eu-trying-to-reduce-dependence-on-china [accessed: 26.03.2024]. ↑