1.Introduction

The fight against climate change is one of the most important challenges facing the international community. It would not be an exaggeration to say that climate change is even the greatest challenge of the modern era. Numerous scientific studies, including reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, clearly indicate the anthropogenic nature of climate change, resulting from, among other factors, the exploitation of the planet’s natural resources, including fossil fuels.[1]

The potential (or already observable) threats posed by climate change could have devastating consequences. These range from obvious risks, such as droughts, floods, or climate-induced migrations, to less obvious ones, such as potential epidemics caused by the release of previously unknown viruses trapped in glaciers.[2]

In order to mitigate the effects of climate change, the international community has concluded numerous agreements, including the Paris Agreement under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). This agreement commits signatories to progressively decarbonize their economies to achieve climate neutrality by the middle of the 21st century. The European Union, as one of the signatories to the Paris Agreement, has introduced its own legal provisions to implement its goals. The European Green Deal, introduced in 2019, outlines European policy actions aimed—like the Paris Agreement—at achieving climate neutrality by 2050. The objectives of the European Green Deal cover a range of areas, including industrial policy, health protection, biodiversity conservation, the development of a circular economy, and sustainable food production.[3]

Poland has committed to adhering to the agreements outlined in both the Paris Agreement and the European Green Deal. For a country whose energy sector has long been heavily dependent on coal, implementing these commitments presents significant challenges. Poland has consistently ranked among the EU countries with the highest coal consumption. In 2024, for the first time, the EU recorded a higher share of solar energy (11%) compared to coal-fired energy, which accounted for less than 10% (9.8%) of the total energy mix. In 16 Member States, coal power contributed less than 5% to the energy mix. Coal-fired power generation in the EU remains largely concentrated in two countries: in 2024, Germany accounted for 39% of the EU’s coal-fired power generation, while Poland accounted for 34%. On an annual basis, Germany reduced its coal power production by 17%, while Poland saw an 8% decline.[4]

It is worth noting, however, that compared to Poland, Germany has significantly greater economic and demographic potential. Additionally, Germany is progressing through the decarbonization process at a faster pace than Poland. This comparison puts Poland in an unfavourable light, highlighting that, on a per capita basis, a statistical Pole relies more on coal-generated energy than a statistical German. However, this does not mean that Poland is not taking steps to support the decarbonization process.

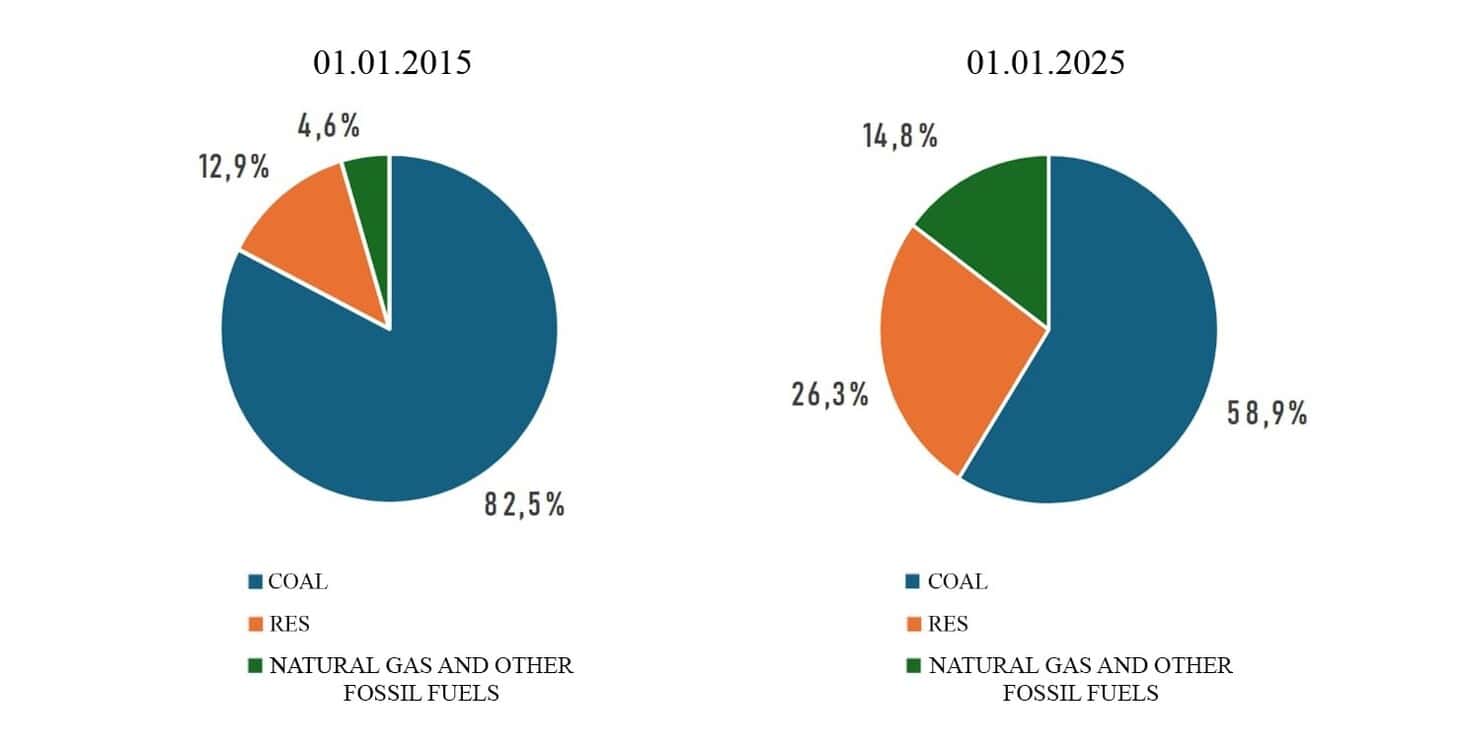

Figure 1: Shares of sources in electricity production

Source: Own elaboration based on estimates by the Forum Energii monthly.

Source: Own elaboration based on estimates by the Forum Energii monthly.

According to estimates by Forum Energii, based on data from ARE, ENTSO-E, and PSE, coal accounted for 58.9% of the Polish power sector in January 2025, while renewable energy sources (RES) made up 26.3%. Comparing these figures to a decade ago, when coal’s share stood at 82.5% and RES at 12.9%, a gradual decarbonization process is evident.[5]

In order to achieve ambitious climate neutrality targets and accelerate the decarbonization process, Poland plans to invest in the construction of its first nuclear power plants. Considering factors such as Poland’s dependence on coal imports, domestic resource depletion, the aging infrastructure of existing coal-fired power plants, international commitments, and the relatively low share of installed capacity in RES, the construction of a nuclear power plant becomes not just an option but a necessity for ensuring the country’s energy security.

In order to better understand the processes involved in building Poland’s first nuclear power plant, it is first necessary to place them in a broader context.

The aim of this article is to analyze the key historical, political, and social factors influencing Poland’s energy transition. As a country heavily reliant on coal, Poland has been relatively late—compared to most European nations—in initiating investments in nuclear energy and faces significant challenges in the process of decarbonization.

At the beginning of the article, I conducted a historical analysis of the significance of coal for Poland from the end of World War II to the early years of democratic Poland (1945–1990). This significance encompasses both the economic dimension of the resource and its role in shaping Polish national identity. The next part of the historical analysis focuses on the causes and consequences of the abandonment of the Żarnowiec nuclear power plant project in the early 1990s and its contemporary implications.

Subsequently, I present statistical data from the CBOS foundation illustrating how Polish attitudes toward nuclear energy have evolved over time, along with an interpretation of the factors behind these changes. The following section continues the historical analysis, this time concentrating on the post-communist period in the context of Poland’s efforts to develop nuclear energy.

In the final part of the article, I examine current initiatives aimed at building the first nuclear power plants in Poland and outline the key challenges the country faces in this regard. The article concludes with personal reflections on the topic and forecasts concerning the future of Poland’s nuclear energy sector.

2.The “coal myth”

After 1945, coal became a key energy resource for Poland. It was at the core of the communist government’s policy, which faced the challenge of post-war reconstruction. Increasing coal extraction was closely linked to the construction of new coal-fired power plants, intended to supply electricity to the emerging industrial, transport, and housing sectors.

Electricity was crucial in meeting the evolving needs of Polish society, driven by urbanization, rural electrification, and industrialization. In addition to domestic consumption, hard coal was also a significant export commodity for Poland. In 1979, a record 41.3 million tonnes of coal were exported.[6] Hard coal was Poland’s only export commodity that provided foreign exchange, essential for state purchases abroad. This strategic importance of coal led to extensive state protection of the sector.[7] In addition, the figure of the miner, regarded as the ‘shock worker,’ aligned with the communist vision of society, reinforcing a positive image of the ‘working people’.

Miners played a key role in the collapse of the communist system in Poland. Numerous strikes and brutal repression against this professional group—including the massacre at the Wujek mine, where nine miners were killed—became a symbol of the struggle against the communist regime. The miners’ strong involvement in the anti-communist opposition, particularly through their activities in NSZZ “Solidarność,” contributed to their positive image in society after the fall of communism in 1989. According to a Public Opinion Research Center (CEBOS) survey published in 2019 on public respect for various professions, miners were highly esteemed by 84% of respondents, placing them among the most respected occupational groups in Poland.[8] It is also worth noting that miners were a very numerous and well-organised professional group for many decades. For more than 30 years, the number of miners has been declining. Back in 1990, there were 388,000 people working in the sector, while in 2015 there were only 98,000.[9]

Given the number of miners, their historical impact, and the high social esteem of their profession, attempts to diversify Poland’s coal-based energy mix were politically challenging. Political support from miners was crucial for two reasons. First, miners represented a significant electorate. Second, protests by miners, who worked in a particularly sensitive energy sector, could lead to unpredictable consequences, such as power outages, demonstrations, and social unrest. Politically, moving away from the traditional narrative of coal as ‘black gold’ and acknowledging the need to reduce its share in the energy sector was, to say the least, a risky decision

3.The first attempt to build the nuclear power plant “Żarnowiec”

The first attempts to expand Poland’s energy mix with nuclear power were made in the 1970s. At that time, Poland already had the scientific background necessary to implement nuclear power. As early as 1955, the Institute for Nuclear Research was established, and in 1958, the first research reactor was built in Poland.[10] Work on Poland’s first nuclear power plant formally began in 1982 at Lake Żarnowieckie, in the village of Krotoszyno. The power station was named “Żarnowiec” after the nearby lake. Despite progress in construction, the project was suspended in 1989. One of the main reasons for the project’s cancellation was growing public opposition to nuclear power, which intensified after the Chernobyl disaster. Another factor was the political turmoil associated with regime change and the collapse of the communist system in 1989. Political instability and financial difficulties faced by the new post-communist government ultimately led to the abandonment of this ambitious project. The cancellation of the Żarnowiec Nuclear Power Plant not only resulted in financial resources being wasted but, more importantly, in the loss of significant human capital. Following the project’s abandonment, specialists in nuclear energy—who, apart from working in the sector, could have trained new generations of experts and contributed to future power plant construction—emigrated from Poland

What would the Polish energy mix look like today if the project had come to fruition? An exact answer to this question is impossible. However, one thing is certain—Poland’s dependence on coal would be lower, and the potential for further nuclear power development would be greater. An interesting point of reference in the history of Poland’s nuclear power industry is the comparison between the Polish “Żarnowiec” project and Slovakia’s “Mochovce”—one of the country’s two nuclear power plants

Construction of units 1 and 2 of the Slovak Mochovce nuclear power plant began in 1983, followed by units 3 and 4 in 1987. As in Poland, work on units 3 and 4 was halted in the aftermath of the political and economic transformation, occurring around the same time but not necessarily in the same year. However, unlike Poland, Slovakia did not abandon the entire project but revisited it in later years. Despite challenges and a prolonged investment process, units 1 and 2 were connected to the grid in 1998 and 1999, respectively. Construction of units 3 and 4 resumed in 2009, with unit 3 connected to the grid in 2023, while unit 4 is expected to be commissioned in 2025.

Thanks to the fact that Slovakia did not abandon its nuclear project in the 1990s, it is now one of the leading European Union countries in terms of the share of nuclear energy in its national energy mix. It can be argued that Slovakia, being a much smaller country than Poland, benefits more significantly from even a single nuclear power plant, as it has a substantial impact on the overall energy landscape. On the other hand, Poland, with its larger GDP and population, had a greater capacity to secure the resources needed to complete the Żarnowiec power plant project. Comparing the capabilities of the two countries, the Polish government’s decision to discontinue the construction of Żarnowiec can be seen as a strategic mistake, the painful consequences of which are still being felt today.

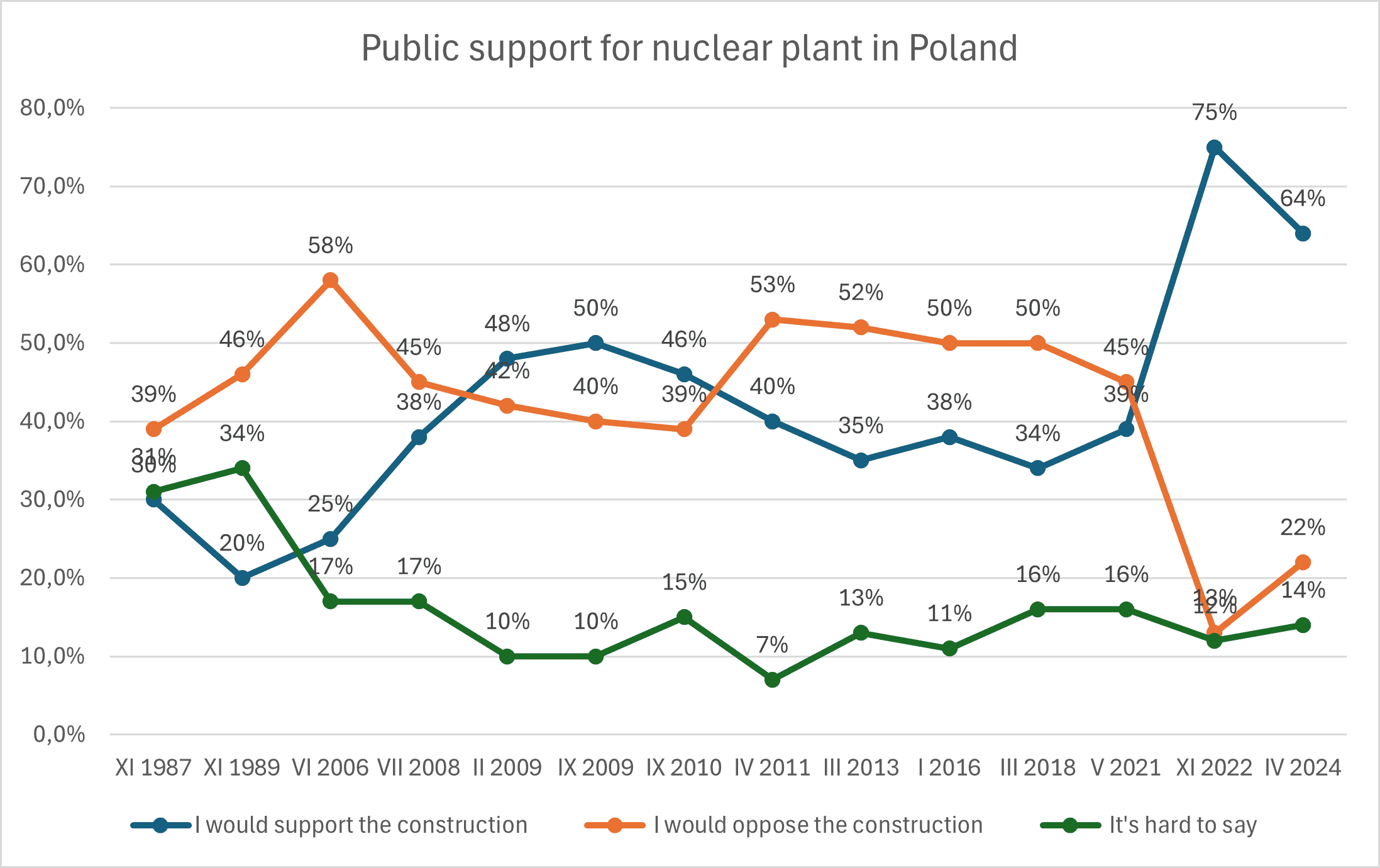

The long-standing neglect of nuclear energy can be attributed to a lack of political will, driven by low public support for this energy source and the traditional attachment of Poles to coal. Figure 2 presents data published by the Centre for Public Opinion Research (CBOS) in its 2024 report, Public Opinion on Energy Policy, in which respondents were asked to express a clear stance on the construction of a nuclear power plant in Poland.

Figure 2: Public support for a nuclear power in Poland

Source: Own elaboration based on CBOS data from “Public Opinion on Energy Policy,” Research Report No. 56/2024

Source: Own elaboration based on CBOS data from “Public Opinion on Energy Policy,” Research Report No. 56/2024

The red line represents the percentage of respondents opposing the construction, the green line indicates those in favour, and the grey line shows those without a clear opinion on the issue. The graph illustrates how public opinion in Poland on this matter has evolved over the years, from 1987 to 2024.

In 1987, support for nuclear power stood at 30%, while 39% of respondents opposed the technology, and 31% had no opinion. By 1989, support had dropped to 20%, opposition had risen to 46%, and the percentage of undecided respondents had increased to 34%. The highest level of opposition was recorded in 2006, reaching 58%, with only 25% expressing support. In 2008, support for nuclear energy increased to 38%, while opposition declined to 45%. In 2009, two surveys were conducted—one in February, where support rose to 48% while opposition stood at 42%, and another in September, where support reached 50% while opposition fell to 40%. In the following years, support for nuclear power remained relatively stable. In 2010, it stood at 46%, in 2011 at 40%, and in 2013, it dropped to 38%, with opposition increasing to 52%. In 2016, support reached 38%, and in 2018, it was 34%, with opposition decreasing from 50% in 2016 to 38% in 2018. A turning point occurred in 2021, when support rose to 39%, while 45% of respondents opposed nuclear energy. A significant shift took place in 2022, with as many as 75% of Poles supporting the construction of nuclear power plants, while opposition dropped to 13%. By 2024, support remained high at 64%, while the number of opponents increased to 22%, and the percentage of undecided respondents stood at 14%.

Based on the presented data, we can attempt to identify correlations between these figures and significant energy-related events that have shaped Polish perceptions of nuclear power.

The first event is the Chernobyl nuclear disaster in 1986, which may have impacted public confidence in this energy source, as reflected in the survey results from 1987 and 1989. The second key event is the 2011 accident at Japan’s Fukushima nuclear power plant. As shown in the graph, 2011 marked a turning point, halting the trend of increasing support for nuclear energy for several years.

The most pivotal and visible moment in recent years occurred in 2022, when Russia invaded Ukraine. This event had severe economic repercussions, including EU sanctions on energy imports from Russia, which significantly disrupted European energy markets. These developments sparked a broad debate on energy security and the urgent need to diversify supply chains in the sector.

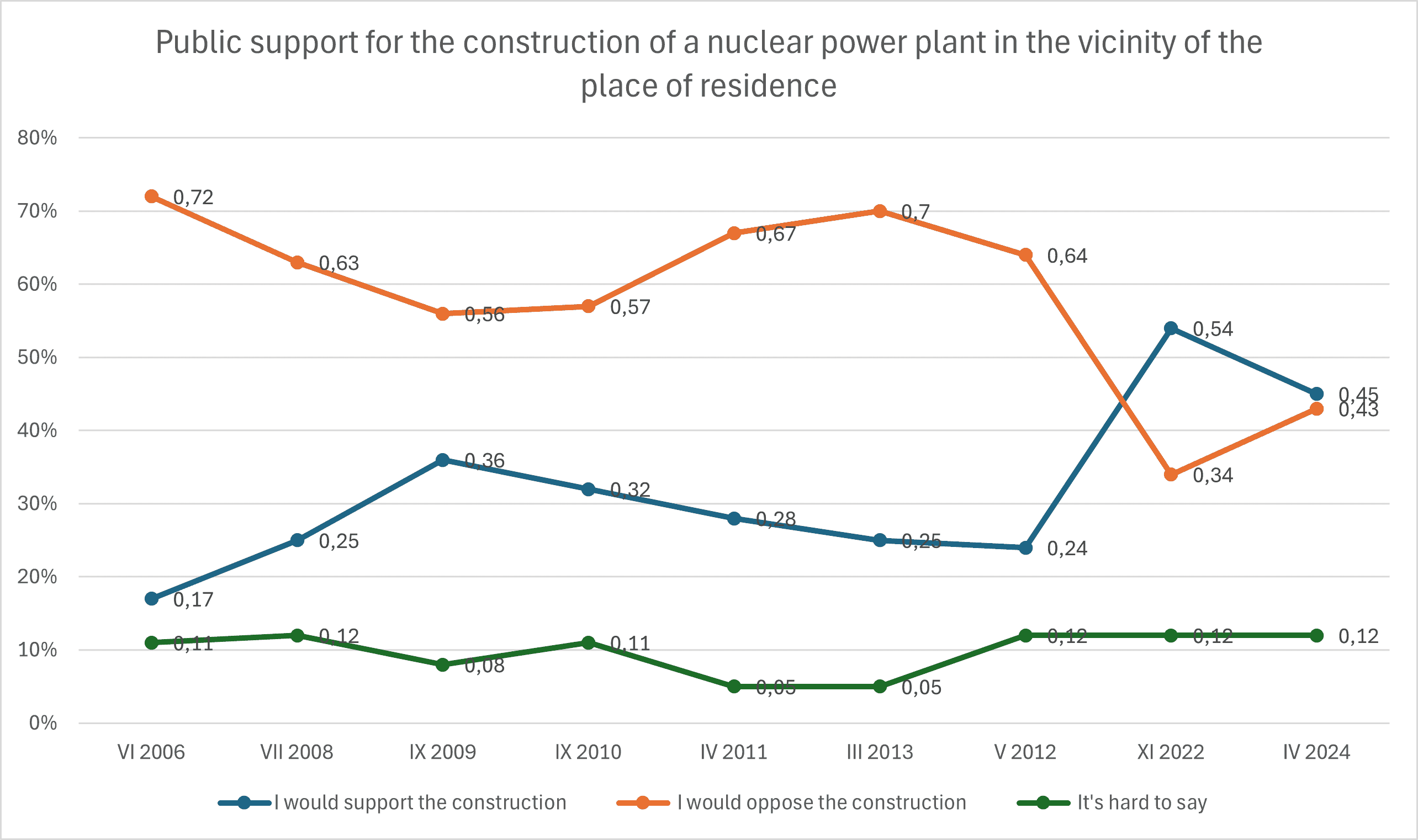

The same communiqué presented data indicating the disappearance of the NIMBY phenomenon concerning the construction of a nuclear power plant. Once again, 2022—the year of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—can be considered a watershed moment. One year before the invasion, 64% of respondents opposed the construction of a nuclear power plant near their place of residence, while only 24% were in favour. In the year of the invasion, the percentage of opponents dropped to 34%, while support rose to 54%.

Figure 3: Public support for the construction of a nuclear power plant in the vicinity of the place of residence – the NIMBY fade [A]

Source: Own elaboration based on CBOS data from “Public Opinion on Energy Policy,” Research Report No. 56/2024

Source: Own elaboration based on CBOS data from “Public Opinion on Energy Policy,” Research Report No. 56/2024

The most recent poll results from 2024 indicate a trend toward a return to pre-invasion public opinion, as the percentages of supporters and opponents of nuclear power plant construction near their place of residence were nearly equal, at 45% and 43%, respectively.

Although the 2024 poll results are not as optimistic as those from 2022, they still confirm a significant shift in the way Poles perceive nuclear power plants in recent years.

4. First steps of nuclear power implementation in democratic Poland

After the abandonment of the Żarnowiec power plant in 1990, politicians made several unsuccessful attempts to revive plans for nuclear power plant construction. In 2005, the government of Prime Minister Marek Belka adopted the document Energy Policy of Poland until 2025, which stated: “Due to the necessity of diversifying primary energy sources and the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the introduction of nuclear power into the national system becomes justified.”[11] However, the document was not legally binding; it was merely a declaration intended to emphasize the importance of nuclear energy in Poland’s energy strategy.

The first serious attempt to build a nuclear power plant in Poland was made by the government of Prime Minister Donald Tusk, who in 2008 announced plans for two such projects. He disclosed this information at a press conference held immediately after the graduation ceremony at Gdańsk Medical University.[12]

The circumstances surrounding the announcement of this key decision for national security may have seemed unusual and raised concerns among the public, particularly among residents of the regions where the power plants were planned. In 2012, the inhabitants of the Mielno municipality, one of the proposed sites, expressed strong opposition to the project. In a local referendum, an overwhelming 94% of voters rejected the construction of the nuclear power plant, effectively halting the project.[13]

It is worth noting that Prime Minister Donald Tusk’s decision came at a time when public support for nuclear power (as shown in Figure 2) was on the rise. However, waves of protests against the construction of a nuclear power plant emerged in 2012, a year when the Fukushima disaster and the anxiety it caused were still fresh in the minds of Poles. Despite the unsuccessful attempt to build a nuclear power plant, a foundation was nonetheless laid for future developments in this sector. In 2010, the company Polskie Elektrownie Jądrowe (Polish Nuclear Power Plants -PEJ) was established, which is now the main state-owned entity responsible for the nuclear project.

The juxtaposition of the government’s policy at the time with public sentiment is not intended to justify those decisions or the abandonment of nuclear plans. The key mistake made by the Polish government in its decision to build a nuclear power plant was, first and foremost, poor communication with the public and a lack of political will, both of which were essential for realizing the project

5.The way forward for the Polish atom

In 2014, the strategic government document Polish Nuclear Power Programme was published as a roadmap outlining Poland’s strategic goals in the field of nuclear energy. It defined, among other aspects, the programme’s main and specific objectives, a timeline for its implementation until 2030, a cost analysis, and the economic rationale for introducing nuclear power in Poland. The document envisioned the construction of the first nuclear power plant, the establishment of an appropriate legal and institutional framework, and the development of a specialized workforce. It also set out the principles for technology and site selection, emphasizing the importance of nuclear safety and the necessity of educational and informational efforts to ensure public acceptance of the project.

As a result of the commitments outlined in the European Green Deal, Poland adopted the goal of achieving climate neutrality by 2050. Consequently, the Polish Nuclear Power Programme of 2014 required an update, which was released in 2020. The revised version of the document is significantly more detailed than its initial edition.

In particular, the timeline for the implementation of nuclear power was revised. The 2014 version projected that the first unit of the initial nuclear power plant would be completed by 2024, a target that was not met. The updated 2020 version of the document postponed this deadline to 2033. Unfortunately, these plans have also been delayed. According to the latest statements from the Government Plenipotentiary for Strategic Energy Infrastructure, construction is now expected to begin in 2028, while the commercial operation of the first unit is anticipated in 2036.[14]

The changes in the updated version of the document also address issues such as the total capacity of the planned power plants, the financing model of the project, site selection, nuclear safety oversight, and its alignment with climate policy. In the 2014 document, these aspects were either presented only in broad and vague terms or were not included at all.

The updated 2020 version of the Polish Nuclear Power Programme sets the total capacity of the new units at 6–9 GW. To better illustrate the scale of the project, it is worth noting that Poland’s annual electricity consumption in 2024 was 168.96 TWh.[15]

Assuming even the lowest estimate for the capacity of the planned nuclear power plants at 6 GW, the new units are expected to generate approximately 52.56 TWh of electricity per year. This implies that if Poland had this nuclear capacity in 2024, nuclear power would have covered nearly a third of the country’s electricity demand, accounting for exactly 31.12% of total consumption. Under the upper, more optimistic estimate of 9 GW of installed capacity, this share would be even higher, with nuclear power supplying nearly half of Poland’s electricity needs—46.67%, to be precise. These figures clearly highlight the significance of this project for the Polish energy landscape.

The updated version of the Polish Nuclear Power Programme document, unlike the 2014 version, also provides a detailed outline of the project’s financing structure. It stipulates that the State Treasury will hold a majority stake of at least 51% in the project’s financing, while the remaining investment costs will be covered by a private investor through contracts established under the CfD (Contract for Difference) mechanism.

This support mechanism guarantees a fixed reference price for the energy producer. If the market price falls below this threshold, the state covers the difference; conversely, if the market price exceeds the reference price, the producer returns the surplus. This system ensures the financial stability of investments while protecting consumers from significant fluctuations in energy prices.

On 20 February 2025, the Polish parliament passed a law to capitalize the company Polish Nuclear Power Plants (PEJ) with PLN 60.2 billion to facilitate the construction of the country’s first nuclear power plant. However, for this transfer of funds to a state-owned company to proceed, approval from the European Commission (EC) regarding state aid is required. The European Commission has not yet issued a decision on the matter, but it is clear that its ruling will play a key role in shaping the future of the project and its implementation timeline. During the Powerpol Congress in February 2025, Deputy Minister of Industry and Government Plenipotentiary for Strategic Energy Infrastructure, Wojciech Wrochna, addressed the issue, stating:

“If the decision is not issued despite the adoption of the law, we will not be able to increase the share capital. If we do not raise the capital, certain investments will not be completed on time, which may cause delays in the project. That is why this timing is crucial. We will make every effort to accelerate negotiations with the European Commission intensively.”[16]

It is worth noting that the decision to subsidise the construction of Poland’s first nuclear power plant was unanimous. Out of the 431 members at the parliament session (29 members did not take part in the deliberations), 430 voted in favour of the law. Only Małgorzata Tracz, a member from the Partia Zielonych (The Greens), voted against it.[17] The result of the vote shows a consensus on the atom among the Polish political elite.

The technology partner for the construction of a nuclear power plant in Poland was announced as the US company Westinghouse Electric Company and Bechtel. On 15 December 2022, a Cooperation Agreement was signed between the parties as a prelude to further, more detailed agreements.[18] On 21 September 2023, a consortium agreement was signed for cooperation in the design and construction of Poland’s first nuclear power plant at the planned Choczewo site in Pomerania,[19] while a few days later, on 27 September 2023, an Engineering Service Contract (ESC) was signed.[20] Both the location and the choice of technology (an AP1000 plant powered by a PWR pressurised water reactor) are in line with the objectives included in the updated version of the 2020 Polish Nuclear Power Programme. The plan calls for the construction of 3 power units at this location with a total capacity of 3.75 GW.

While the conclusion of these agreements with the US investor is positive news, it should be added that these are not the only agreements necessary for the nuclear project. The ESC contract stipulated that the nuclear power plant project would be ready by the end of March 2025, but the Polish company PEJ has indicated that there is a risk that this deadline will be delayed and that this contract will need to be extended. The next step will be the conclusion of an Engineering Development Agreement (EDA) and, in the next stage, the signing of a full performance contract setting out the terms of implementation, financing and repayment of the investment (EPC- Energy Performance Contracting).[21]

Investment safety is supervised by the State Atomic Energy Agency (PAA), whose tasks include inspecting nuclear facilities, issuing licences, monitoring the radiation situation, developing regulations and responding to potential threats.

It is worth mentioning that a positive position for the construction of a nuclear power plant in the Baltic Sea was expressed by all countries invited to foreign consultations with the Polish side (14 countries in total). The countries invited for consultation were the Czech Republic, Finland, the Netherlands, Austria, Belarus, Denmark, Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia, Germany, Slovakia, Sweden, Ukraine, Hungary. The countries with a long anti-nuclear tradition – Germany and Austria – submitted the most written comments on the draft. However, the doubts of neighbouring countries were clarified by the Polish side.

In conclusion, we can observe concrete actions and decisions regarding the construction of the Choczewo nuclear power plant. Although the work is, for the time being, mainly of a clerical nature, we can be sure of a few things, such as the choice of investor, technology and the location of the facility. In addition, the project timetable remains uncertain due to the ongoing process of obtaining approval from the European Commission for the transfer of public funds to the PEJ company

6. Logistical challenges

The construction of Poland’s first nuclear power plant will be accompanied by a number of infrastructural accompanying projects that are essential to the logistics of the entire project. The most important accompanying projects include: Construction of a national road linking the S6 expressway with the nuclear power plant (planned completion – 2029); construction of new and modernisation of existing railway connections (planned completion – 2029); construction of a MOLF offshore unloading structure enabling the transport of oversized elements (planned completion – 2028); the construction of a substation to allow power to be fed into the grid (planned completion – 2034); and the construction of electricity connections to provide power to the construction site and subsequent operation of the power plant (planned completion – 2027).[22]

As can be seen, the construction of a nuclear power plant is a multi-dimensional undertaking. A key challenge for those responsible for the above-mentioned investments will be to ensure that work proceeds in such a way as not to create delays. A nuclear power plant is a system of interconnected vessels and problems arising in one associated investment can affect the project as a whole.

In addition to infrastructure, another logistical challenge in the construction of a nuclear power plant will be the acquisition of adequate human resources (a challenge that would have been easier had work on the Żarnowiec power plant described above not been interrupted in the 1990s). In December 2023, the Ministry of Climate and Environment published a ‘Human Resources Development Plan for Nuclear Power’, assuming a significant increase in employment in the sector, the development of human resources for PEJ and PAA and the need to strengthen the budget of key institutions. The plan envisages cooperation with Polish universities, such as UMCS (Maria Curie-Skłodowska University), Gdansk University of Technology or AGH (AGH University of Science and Technology), to train specialists. In addition, due to the shortage of qualified human resources, it will be necessary to support experts from abroad and specialists from other fields, such as thermal power engineering, electrical power engineering or mechanical engineering.[23]

We do not yet know the details of securing the key supply chains of the necessary components for the construction of the power plant and nuclear fuel. In the case of the latter, we can assume that the supplier (for the first years of the plant’s operation), will be the technology provider, i.e. Westinghouse, as is common practice in projects of this kind.

The storage location of the radioactive waste is also in question.[24] Failure to act on this issue could be a calculated political decision. The topic of radioactive waste could cause a fuss in the media, and this could in turn negatively affect, the record support for a nuclear power plant in Poland.

7. A second nuclear power plant

The latest version of the government’s 2020 PPEJ plan (Polish Nuclear Energy Program) requires an update, which was due to be released as early as 2024. Although work is still underway on the updated version of PPEJ, we can assume that the plan to procure between 6 and 9 GW of nuclear electricity by 2033 is not realistic. The obtainable capacity from the Choczewo nuclear power plant will be 3.75 GW and this is the only concrete information we have at the moment. The Polish government, as described above, maintains the course adopted in the PEJ 2020 with regard to the Choczewo power plant. The future updated version of the PPEJ will focus on the identification of four potential sites for a second nuclear power plant (Bełchatów, Konin, Kozienice, Połaniec), the inclusion of plans for small modular reactors (SMRs), and further analyses and consultations on the selection of the final site and technology partners.[25]

In contrast, we already know that the foreign investor responsible for the construction of the second nuclear power plant will be selected through a competitive tender process-unlike the first nuclear power plant, where the choice of the American investor was a purely political decision. Countries such as Japan, South Korea, France and the USA have expressed their desire to realise a second nuclear power plant project in Poland.

The choice of location for the second nuclear power plant is dictated primarily by the availability of existing infrastructure. Coal-fired power plants have operated or are still operating in the locations indicated. In addition to access to infrastructure, the choice of these locations may bring additional benefits to the residents of these cities, in the form of job retention, development of the local economy, increased investment in road and technical infrastructure, improved air quality through reduction of pollutant emissions, and increased tax revenues that can be allocated to regional development. An example of benefits for the local community can already be seen in the region of the first nuclear power plant in Pomerania, as Polskie Elektrownie Jądrowe concluded three-year framework agreements earlier this year for the repair, construction and modernisation of local roads in the vicinity of Poland’s first nuclear power plant.[26]

8. Conclusions

The landscape of the Polish energy sector, shaped by its political, historical, and social implications, is unique in Europe. No other European country has faced as challenging a transition away from coal as Poland. For many years, Polish coal was not only the backbone of the economy but also a key element of identity for many—miners, shipbuilders, and industrial workers alike.

Polish society, long tied to coal, did not see the need to diversify its energy sources. It was reluctant to acknowledge that coal reserves—like the lifespan of coal-fired power plants—would eventually be depleted. Nor did it want to recognize that more efficient and stable energy sources existed. Over the decades, Polish coal developed a sort of cult status, and any criticism of it was perceived as an attack on national identity.

The shift in public perception toward nuclear power, which can be seen as a counterbalance to the ‘coal myth’ described in this article, is a relatively recent phenomenon in Poland. Although the Polish energy sector is still predominantly coal-based, the transition away from this reliance is becoming a reality.

While Poland is now on track to pour the first concrete for its first nuclear power plant, the situation remains subject to change. It is crucial to remember the history of the Żarnowiec nuclear power plant—the biggest energy policy failure in Poland’s history. The abandonment of such an advanced investment continues to impact the Polish energy sector today. Had Żarnowiec been completed, further expansion of the nuclear sector would have been much smoother.

A complete halt to Poland’s nuclear program seems unlikely. Unlike the Żarnowiec project, the construction of current nuclear power plants is now a necessity. As a member of the European Union, Poland is obligated to decarbonize its economy—something that, given the current energy mix, is impossible without nuclear energy.

In the coming years, progress on nuclear power plants in Poland will not be spectacular. The current phase involves extensive legislative work, including obtaining permits, conducting tenders, signing various agreements, and drafting strategic plans. However, the lack of high-profile news should not be mistaken for stagnation. On the contrary, significant progress is being made. Given the complexity of nuclear projects, careful adherence to procedures is crucial to ensuring safety. The multistage nature of the process may also serve to reassure nuclear sceptics.

Although Poland’s nuclear investments and plans come decades later than they should have, they nonetheless offer a reason for optimism. If Poland stays on its current course, nuclear power plants will become a permanent part of the country’s new low-carbon energy mix, forming the foundation of its future development.

Endnotes

[A] NIMBY (an acronym for Not In My Back Yard)- a pejorative term for the attitude and activism of people who express their opposition to certain investments in their immediate neighbourhood, although they do not deny that they are needed in general (source: Wikipedia). In this article, I rely on data from CBOS, although it should be mentioned that there are various public opinion polls on this issue. In the media, it is often reported that there is “record support for nuclear power in Poland” reaching over 90%. This kind of information is often reproduced on the basis of research carried out by the research agency DANAE on behalf of the Ministry of Industry, which may raise some doubts about the reliability of the research. Surveys commissioned by government institutions, especially those supporting a particular political agenda, should be analysed with an appropriate degree of criticism. However, regardless of the poll chosen and the percentage differences, the growing support for nuclear power in Poland in recent years is a fact.

References

[1] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Summary for Policymakers. Edited by Hoesung Lee and José Romero. Geneva, Switzerland: IPCC, 2023.

[2] Kaczmarek, Krzysztof. „The Impact of Climate Change on Security”. Journal of Modern Science 58, nr 4 (22 wrzesień 2024): 410–30.

[3] ibiden

[4] Ember, European Electricity Review 2025, January 23, 2025, 12

[5] Miesięcznik Forum Energii: Styczeń 2025 – Podsumowanie – Nowa Energia, 10 luty 2025. https://nowa-energia.com.pl/2025/02/10/miesiecznik-forum-energii-styczen-2025-podsumowanie/.

[6] Sobel, Michał. Tradycyjne i perspektywiczne kierunki eksportu polskiego węgla. Polityka Energetyczna, Tom 8, Zeszyt specjalny, 2005, 309-318.

[7] Bednorz, Jarosław. 35 lat reformowania górnictwa węgla kamiennego w Polsce. Zeszyty Naukowe Instytutu Gospodarki Surowcami Mineralnymi i Energią PAN 1(112) (2024): 127–142.

[8] Fundacja Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej. Które zawody poważamy? Komunikat z badań nr 157/2019. Warszawa: CBOS, 2019.

[9] Szpor, Aleksander, i Konstancja Ziółkowska. The Transformation of the Polish Coal Sector. Winnipeg: International Institute for Sustainable Development, 2018.

[10] Jagoda Ulewicz, Justyna Chodkowska-Miszczuk, and Agata Lewandowska, “Sprawiedliwie – Co to Znaczy? Transformacja Energetyczna W Polsce Na Tle Społeczno-przestrzennych Konsekwencji Nieukończonej Elektrowni Jądrowej „Żarnowiec”,” 2023, https://open.icm.edu.pl/handle/123456789/23369.

[11] Ministerstwo Gospodarki i Pracy, Polityka Energetyczna Polski do 2025 Roku (Zespół do Spraw Polityki Energetycznej, 4 stycznia 2005).

[12] trojmiasto.pl. „Tusk: Będą dwie elektrownie atomowe”, 9 listopad 2008. https://www.trojmiasto.pl/wiadomosci/Tusk-Beda-dwie-elektrownie-atomowe-n30385.html.

[13] Forbes.pl. „Mielno przeciw atomowi – referendum na «nie»”, 13 marzec 2025. https://www.forbes.pl/wiadomosci/referendum-ws-lokalizacji-elektrownii-atomowej-w-gaskach/e0zzcdw.

[14] Energetyka24. „Pierwszy blok elektrowni jądrowej zacznie pracę w 2036 r. Nowy pełnomocnik pokazuje harmonogram.” Ostatnia modyfikacja 6 marca 2024. Dostęp 14 marca 2025. https://energetyka24.com/atom/wiadomosci/pierwszy-blok-elektrowni-jadrowej-zacznie-prace-w-2036-r-nowy-pelnomocnik-pokazuje-harmonogram.

[15] ISBnews. „PSE: Krajowe zużycie energii elektrycznej wzrosło o 0,86% r/r w 2024 r.” WysokieNapiecie.pl, 3 lutego 2025. Dostęp 14 marca 2025. https://wysokienapiecie.pl/krotkie-spiecie/pse-krajowe-zu-ycie-energii-elektrycznej-wzros-o-o-0-86-r-r-w-2024-r/.

[16] Ministerstwo Przemysłu. „Dialog z Komisją Europejską w kwestii finansowania atomu jest kluczowy.” Gov.pl, 24 lutego 2025. Dostęp 14 marca 2025. https://www.gov.pl/web/przemysl/dialog-z-komisja-europejska-w-kwestii-finansowania-atomu-jest-kluczowy.

[17] BiznesAlert.pl „Polska chce dofinansować swój atom 60 miliardami złotych. Potrzebna jest decyzja Brukseli”. 21 lutego 2025. https://biznesalert.pl/dofinansowanie-polskiej-elektrowni-jadrowej-glosowanie-sejm-pej-atom/.

[18] Gov.pl. „Polskie Elektrownie Jądrowe i Westinghouse Electric Company podpisały umowę określającą zasady współpracy przy przygotowaniu procesu budowy pierwszej elektrowni jądrowej w Polsce”. 2025. https://www.gov.pl/web/klimat/polskie-elektrownie-jadrowe-i-westinghouse-electric-company-podpisaly-umowe-okreslajaca-zasady-wspolpracy-przy-przygotowaniu-procesu-budowy-pierwszej-elektrowni-jadrowej-w-polsce.

[19] Westinghouse Electric Company. „Westinghouse i Bechtel podpisują umowę konsorcjum dla pierwszej w Polsce elektrowni jądrowej”. 2025. https://info.westinghousenuclear.com/poland/news-and-insights/westinghouse-i-bechtel-podpisuja-umowe-konsorcjum-dla-pierwszej-w-polsce-elektrowni-jadrowej.

[20] Westinghouse Electric Company. „Historyczna umowa umożliwia rozpoczęcie prac dla wskazanej lokalizacji pierwszej w Polsce elektrowni jądrowej”. 2025. https://info.westinghousenuclear.com/poland/news-and-insights/historyczna-umowa-umozliwia-rozpoczecie-prac-dla-wskazanej-lokalizacji-pierwszej-w-polsce-elektrowni-jadrowej.

[21] Agnieszka Skorupińska, Dominik Brodacki. Energetyka jądrowa w Polsce: Ocena gotowości do budowy pierwszej elektrowni. Redakcja Baker McKenzie i Polityka Insight. Warszawa: Baker McKenzie, Polityka Insight, 2025.

[22] ibiden

[23] ibiden

[24] ibiden

[25] Jędrzej Stachura, „Polska zaktualizuje program jądrowy. Nowy wejdzie za kilka dni, ale z kilkumiesięcznym opóźnieniem”. BiznesAlert.pl. 6 marca 2025. https://biznesalert.pl/polska-ppej-atom-energetyka-europa-program/.

[26] Nuclear.pl. „PEJ: 25 milionów zł na lokalne drogi w rejonie elektrowni jądrowej do 2028 roku”. 5 marca 2025. https://nuclear.pl/wiadomosci,news,25030501,0,0.html.