This contribution is part of the book “The Dragon at the Gates of Europe: Chinese presence in the Balkans and Central-Eastern Europe” (more info here) and has been selected for open access publication on Blue Europe website for a wider reach. Citation:

Ganchev, Ivo, Making the Case for a New Coherent Bulgarian Strategy towards China: A Practitioner’s Analysis of Bilateral Political and Economic Relations (2015-2022), in: Andrea Bogoni and Brian F. G. Fabrègue, eds., The Dragon at the Gates of Europe: Chinese Presence in the Balkans and Central-Eastern Europe, Blue Europe, Dec 2023: pp. 431-480. ISBN: 979-8989739806.

1. Introduction

Bilateral relations are a fundamental element of international politics; they involve not only intergovernmental interactions, but also various other aspects such as economic engagement and exchanges between people and organizations (Pannier, 2020). This chapter aims to evaluate and conceptualize the state of political, economic, and business dimensions of Bulgaria-China relations, which involve pressing challenges that require quick responses from the Bulgarian side. Other aspects of bilateral relations, such as security policy, educational and cultural exchanges between the two countries, fall beyond the scope of this chapter as their current state contains far fewer issues demanding urgent policy adjustments.

Compared to China’s relations with most other European countries, Bulgaria-China relations have received very little attention in academic literature and policy reports in recent years. This chapter focuses on the period between 2015 and 2022 for two reasons: first, the most recent extensive in-depth study of Bulgaria-China relations (Tian, 2015) was published in 2015 and it covers most key developments until that point in time; and second, this period begins shortly after the launch of the Belt and Road Initiative[1] (BRI), signalling a deepening in China’s engagement with the world (Wu and Zhang, 2013).

Recent comprehensive research projects have focused on examining the relations between China and Eastern or Central and Eastern Europe as a whole, dedicating relatively little attention to the case of Bulgaria. Meanwhile, academic studies focused on Bulgaria-China relations often zoom into specific topics, such as trade and investment (Hristova-Balkanska et al., 2022), economic diplomacy (Sokolov, 2021), sister cities (Tian and Tian, 2022), translation of popular literature (Chen, 2020), or the study of Bulgarian language in China (Lin, 2020), among others.

The broader Western debate regarding the pros and cons of engagement with China is largely absent from the Bulgarian public sphere, although it does take place indirectly between scholars and outlets who never interact with each other directly. On one side, NGOs that receive funding from the US have published several reports (see, e.g., Shopov, 2022; Stefanov, 2022) cautioning about potential risks that Bulgaria could face as a result of engagement with China. On the other side, Bulgarian partner outlets of the Chinese Media Group (see, e.g., 24 Chasa, 2023a; Milanov, 2023) often publish positive appraisals of China’s development and interviews with experts that support deeper engagement between Bulgaria and China.

These types of writings rarely attract any substantial attention from the Bulgarian or the Chinese government and business communities or from the general public. One reason for this is that, as Stefanov (2022) rightly points out, “Bulgaria has never been among Beijing’s foreign policy priorities, and the feeling has been mutual”. In this context, strong stances for or against engagement with China always seem overly-critical or overly-optimistic and say more about the stances of their authors than about the subject that they explore.

Governments and businesspeople are rarely concerned about hypotheticals, failed project proposals, radical ideas for sharp reorientation of national policy or wishful thinking. Hence, this chapter purposefully steers away from engaging in a discussion about the merits and shortcomings of engagement with China. Instead, it explores how political, economic and business engagement between China and Bulgaria takes place and what outcomes it has produced. The aim is to derive policy proposals for the Bulgarian government and business community to adjust their approach and strive to produce more favorable outcomes in line with Bulgarian national political and economic interests within the current framework of bilateral relations with China.

This chapter applies a scholarly academic approach to discuss trends and issues that are of primary concern to practitioners shaping Bulgaria-China relations. It heavily relies on primary sources and media reports that are openly available to illustrate key trends and exemplify them with relevant case studies. Some sources report financial data in EUR, while others report it in USD; this chapter has quoted all said data in the currency that it was originally reported in to avoid potential distortions that could arise due to fluctuations in exchange rates over time. As the title suggests, the chapter argues that bilateral relations are characterized by untapped potential and there is greater room to maximize the benefits that Bulgaria can obtain from its engagement with China. One key reason for this is the dispersion of actors who lack coordination and have no pre-established joint aims or intended outcomes. The body of the chapter is divided into three parts, which analyze political, trade and business (including investment) relations between China and Bulgaria. The analysis is followed by a conclusion that calls for a new coherent Bulgarian strategy in its relations with China and presents ten practical recommendations that should be aptly implemented by the Bulgarian government.

2. Political Relations

Official foreign relations between countries are most often shaped by interactions between central governments, which are supported by embassies; however, local governments and other arms of the state at different levels can also play a role in the process. Interactions between central governments are most fruitful when leader visits take place. This aspect of international politics has had a particularly strong significance for China, where the State Chairman[2] and the Premier hold a particularly high degree of decision-making power and an elaborate system of bureaucratic institutions often works meticulously to convert them into tangible outcomes. Some scholars have created databases of Chinese leaders’ visits abroad and in-person meetings with their counterparts to trace correlations between their changing nature and shifts in trends of Chinese foreign policy and bilateral relations with other states (e.g., Kastner and Saunders, 2012; Wang and Stone 2023). Others have used them as an explanatory variable for deepening economic relations (Nitsch, 2007; Lin, Yan and Wang 2017), partly through the launch of new agreements or partnerships signed during the visits to stimulate business engagement in various areas.

The 2017-2022 period of Bulgaria-China relations featured one notable high-level state visit by a Chinese top-level political leader to Bulgaria. It took place in 2018 when Chinese Premier Li Keqiang visited Sofia to attend the 7th China-CEEC[3] summit and met with Bulgarian PM Boyko Borissov. This was the second trip by a Chinese leader to Bulgaria since 1989, following the visit of Premier Zhu Rongji who visited Sofia for two days in 2000, before embarking on a two-week European tour of six-countries (South China Morning Post, 2000). Due to the rarity of visits by Chinese leaders to Bulgaria the personal interaction between Li and Borissov in 2018 was an important symbolic sign of goodwill for both sides.

From a practical standpoint, this high-level meeting led to the conclusion of several bilateral framework agreements for economic engagement (Tashkova, 2018), which set up potential pathways towards realizing concrete deals. Most of these were continuations of previous engagements, such as an EUR 86m order by the Bulgarian Navy for the production of six cargo ships. This type of cooperation began back in 2010 and up to 2021, the Bulgarian Navy received 16 ships produced by Jiangsu New Yangzi Shipbuilding (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Bulgaria, 2021). Since then, media announcements about the delivery of more new ships to Bulgaria have also emerged (24 Chasa, 2023b).

However, many of the other framework agreements were designed in a way that made their fulfilment highly unlikely. For instance, the Bulgarian Development Bank (BDB) signed a document for the potential provision of up to EUR 1.5b worth of loans by the Chinese Development Bank (CDB) for joint financing of various projects. This built on previous similar agreements for the provision of EUR 5m and EUR 80m, signed in 2009 and 2017, respectively (Bulgarian Development Bank, 2023). However, according to one of its recent annual reports (Bulgarian Development Bank, 2022), the total valuation of all assets held by the BDB as of 2021 was only around EUR 1.65b. Besides, public announcements indicate that all active loans over EUR 30m amount to an estimated value between EUR 400m and EUR 500m (BTV, 2021b). This shows a considerable mismatch between the scale of the potential deal and the capacity of the bank, which means that its full potential is de facto impossible to realize.

Another agreement was a request to purchase up to 10,000 tons of tobacco per year, which is about 60 to 70 per cent of the total produced in Bulgaria (Agri BG, 2018) but remains a relatively small quantity from the perspective of China, which is the largest grower of tobacco in the world, producing approximately 2.2 million tons of tobacco annually (Statista, 2023). This development received widespread media attention and was rightly described by one Bulgarian TV host as a “courtesy” from Li Keqiang to his counterpart Borissov (Bulgaria on Air, 2018); it came about as a follow-up of earlier discussions dating back to 2015 when Bulgarian exporters first expressed interest in making deals with China. However, later reports revealed that over one year after its signing, the tobacco agreement proved difficult to benefit from; before the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Chinese customs experts were still working with the Bulgarian Food Safety Agency to address technical issues and no follow-up announcements have emerged since then (Popov, 2019). In this case, the issue is not purely technical but also organizational: there are many small Bulgarian tobacco producers who are dispersed and prefer making deals with buyers who can partly pay in advance. Thus, it would be nearly impossible to devise a mechanism for providing quantities that satisfy the stated Chinese demand to begin with, which suggests that the agreement was primarily signed for publicity.

While this is only a sample of framework agreement cases, it already illustrates several pertinent points. First, there is a strong political incentive to sign cooperation documents during leader visits; second, some of them can indeed materialize, if they are realistic; and third, those that do not yield specific outcomes are often problematic due to flaws in the stipulated scope or other specific conditions. If the Bulgarian government is indeed seeking to promote the completion of bilateral deals, it must ensure that the selection of projects and the potential engagement terms are appropriate. Leading up to state visits, Chinese officials are often under pressure to conclude agreement texts with the other side for reasons of publicity and professional growth in the bureaucratic hierarchy. These rare opportunities to conclude large-scale deals have short time windows and often remain underexploited by the Bulgarian government.

During the 2015-2022 period, there were also several visits by Bulgarian leaders to China. The first one came in 2015 when Borissov attended the 4th China-CEEC summit in Suzhou, where Foreign Ministers Daniel Mitov and Wang Yi signed an agreement for Bulgaria to join the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), alongside Poland, Serbia, Slovakia and the Czech Republic (Trud, 2015). Several Bulgarian yoghurt and rose oil companies also signed some agreements for potential cooperation to set up joint production facilities in China (for more details, see Kapital, 2015); however, this was a considerably less substantial opportunity compared to the 2018 visit by Li in Sofia.

During his time in China, Borissov also visited the mayor of Shanghai who had just agreed to sign a sister city partnership with Sofia (Mediapool, 2015). Nevertheless, there were few concrete outcomes of this visit and many Bulgarian media outlets ended up focusing on the fact that Borissov’s delegation ran into problems with Chinese airport security (Maritsa, 2015), rather than touting his achievements. Over the years, Borissov has had several other interactions with Li (e.g., at some of the China-CEEC summits) and occasionally received delegations with Chinese politicians (e.g., Zhang Qingli[4]) in Sofia as well, but none of these engagements were as substantial as the 2018 visit of Li to Sofia.

Another highly-ranked political figure in Bulgaria, President Rumen Radev, visited China in June 2019, attending three business forums (Dalian, Beijing and Shanghai) and three high-level meetings with Xi Jinping, Li Keqiang and Li Zhanshu[5]. Most notably, he signed a bilateral agreement to elevate Bulgaria-China relations to a “strategic partnership”. This is one of 24 types of partnerships which China has signed with foreign countries and other counterparts (Li and Ye, 2019). Eleven of these types are different variations of a “strategic partnership” and they generally indicate intentions to pursue a high-level of engagement. However, this does not always happen in practice; in total, as of 2022 China has signed 110 strategic partnerships (Boni, 2022) with counterparts that have highly diverse levels and depth of engagement with Beijing. Hence, this development can be understood as a pre-condition for potential future developments, rather than an achievement in and of itself. In fact, the European Union (EU) signed a “comprehensive strategic partnership” with China as early as 2003 (Mission of the People’s Republic of China to the European Union, 2023), so from a broader geoeconomic standpoint, one could make a strong case that Bulgaria should have upgraded its relations with China and sought to obtain greater benefit from them more pro-actively and at a much earlier stage.

During his time in China, Radev made three concrete proposals, namely, the launch of direct flights to Bulgaria, the opening of a branch by a Chinese bank in Bulgaria and the establishment of a common scientific research center in Sofia (Mediapool, 2019). Only the latter resulted in a specific outcome, the opening of a Bulgarian-Chinese Innovation Centre affiliated with Sofia University (China Radio International, 2020). Still, the practice of coming up with concrete demands shows the intention to formulate Bulgarian interests with greater clarity than before. To improve the chances of success in such circumstances, these could be further coordinated with the executive government of Bulgaria and packaged in a way that is likely to emphasize the concrete benefits that both sides could obtain, in order to make a more convincing case.

The start of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 led to travel restrictions which prevented further leader meetings at the highest level and it is yet unclear when they might resume. To commemorate the 70th anniversary of Bulgaria-China diplomatic relations, Borissov spoke to Li by phone. Ministerial level engagements related to the BRI and China-CEEC summits (attended by Bulgarian Deputy Prime Minister Mariyana Nikolova in 2021) have continued, but no new major breakthroughs have been achieved since 2020. It is also important to note that between 12 May 2021 and 5 June 2023, Bulgaria had five separate governments (four caretaker governments and one four-party coalition), headed by three different prime ministers. It is unclear whether governments with a short time horizon would have prioritized arrangements to meet Chinese political leaders, or whether the latter would have been interested in such activities.

Nevertheless, two institutions which continued to function during this period were the respective embassies of Bulgaria and China, which resolve daily matters related to bilateral relations and intensively help with the preparation of high-level meetings. Most Bulgarian Foreign Ministry officials begin their speeches and writings by pointing out that their country was the second one to recognize the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, and it has conducted bilateral relations in accordance with the “one China policy”. They often continue by praising the efforts of China to set up the China-CEEC summits and the BRI, quoting the recently-upgraded status of bilateral relations to a strategic partnership and stating that China is a partner of great priority for Bulgaria in Asia (see, e.g., Orbetsov, 2021, p. 106). These types of diplomatic statements create conditions for further dialogue on demand, but do not outline a concrete vision for bilateral relations between the two countries.

Due to the large difference between the size of Bulgaria and China, the Bulgarian embassy has a much harder job than the Chinese embassy, since it must employ its limited resources to engage in events of a much larger scale. Nevertheless, it has continuously provided solid support to the Bulgarian community in China, and to various business-related and cultural organizations which promote bilateral engagement, as well as to the Bulgarian community at large. After Ambassador Grigor Porozhanov completed his mandate in mid-2021, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs did not nominate his successor and since then, the diplomatic mission has been led by chargés d’affaires ad interim Ivaylo Yordanov. In February 2023, career diplomat Andrey Tehov was appointed (Presidency of Bulgaria, 2023) but as of mid-2023 he is yet to arrive in Beijing. This two-year delay in dispatching a new ambassador is inconsistent with the narrative that China is a partner of high priority for Bulgaria – although it does not have a direct impact on ongoing daily affairs, it is likely to have a minor impact on the credibility of the Bulgarian side in upcoming inter-governmental engagement with China.

Meanwhile, the Chinese embassy in Bulgaria is highly active and makes a strong effort to publicize its activity and relevant announcements. The Chinese version of its website as well as its Facebook page (in Bulgarian) are updated on a particularly frequent basis. In the months after his appointment in February 2019, Ambassador Dong Xiaojun had a wide range of courtesy meetings with then-PM Borissov and President Radev, as well as with various other senior politicians, such as Foreign Minister Ekaterina Zaharieva, Vice-President Iliana Yotova, and President of the National Assembly of Bulgaria Tsveta Karayancheva, among others. The embassy provides remarkably frequent support to various economic forums and cultural activities, and has been able to secure the delivery of speeches by senior politicians such as Yotova at Chinese New Year celebrations.

Since it is unrealistic to expect a multi-fold increase in the number of Bulgarian diplomats and official representatives in China the Ministry of Foreign Affairs will dedicate should explore alternative strategies to address asymmetries in the bilateral relationship. One such strategy could be encouraging the embassy in Beijing to search for non-traditional ways of expanding Bulgarian influence in China. This is necessary both to make up the gap in the level of influence that the Chinese embassy (and China at large) is able to develop in Bulgaria, and to perform its duties and deliver input before high-level political engagements more efficiently. One potential strategy to do this is mobilizing the efforts and connections of established Bulgarian senior professionals who are long-term residents of China, and helping to achieve greater coordination between organizations that work for deepening of Bulgaria-China relations. Another measure to make up the deficit in access to political elites and network-building would be engaging more pro-actively and more frequently with selected provincial governments in China. While such non-traditional practices are not a core element of the traditional diplomatic protocol, they could provide a pragmatic solution for Bulgaria to addressing bilateral asymmetries in its relations with China and better defend its national interest.

3. Trade Relations

The most essential aspect of the economic relations between Bulgaria and China is trade; to understand its bilateral dimension, it is important to begin by analyzing the role of China as a trading partner for Bulgaria. There are two databases with data on trade between Bulgaria and China; the first one is published by the National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria (NSI, 2023) and the second one is published by the General Administration of Customs of the PRC (GAC-PRC, 2023). These two databases contain considerable inconsistencies in terms of specific numbers related to trade between Bulgaria and China, but broadly speaking, they reveal similar trends. The NSI database contains information about Bulgarian trade with various countries and as of mid-2023, it only presents comprehensive statistical information about trade with both China and other partners for 2020 and 2021, which are relatively similar. First, the latest available data (from 2021) will be briefly examined to contextualize the role of China as a trade partner of Bulgaria; then, the Chinese Customs database will be analyzed to perform a more detailed analysis of fluctuations in bilateral trade flows.

According to the NSI (2023), in 2021, the total amount of Bulgarian imports and exports globally was EUR 74.7 billion, including EUR 46.74 billion (62.6%) trade with EU partners and EUR 27.96 billion (37.4%) with non-EU partners. This dataset claims that the total amount of trade with China is worth EUR 3.24 billion, which accounts for 11.60% of Bulgaria’s total non-EU trade; only two other partner countries outside of Europe accounted for larger amounts of trade with Bulgaria, namely Turkey (18.67%) and Russia (12.00%). However, as both European and Bulgarian relations with Russia are set to continue deteriorating due to the war with Ukraine, China is highly likely to become Bulgaria’s second most important trade partner.

Although the trade deficit of Bulgaria quoted in the NSI data and the Chinese customs data differs, both indicate that it is significant. The NSI (2023) reports that in 2021 the value of Bulgarian exports to China were worth EUR 1.12 billion but imports were valued at EUR 2.12 billion, which results in a deficit of EUR 1 billion. In other words, although in the same year trade with China accounted for only 4.34% of Bulgaria’s total trade volume, the imbalance in this bilateral relationship yielded 23.5% of its Bulgaria’s global trade deficit. Meanwhile, for the same year, the GAC–PRC (2023) estimates that the trade deficit of Bulgaria vis-à-vis China was only USD 0.5 billion for 2021. A discussion of the reasons behind these inconsistencies is beyond the scope of this chapter and it would be speculative due to the lack of clarity regarding the methodology of data collection and analysis. Nevertheless, even if the lower number was taken at face value, China would still account for 10.9% of Bulgaria’s global trade deficit, which is a considerable number.

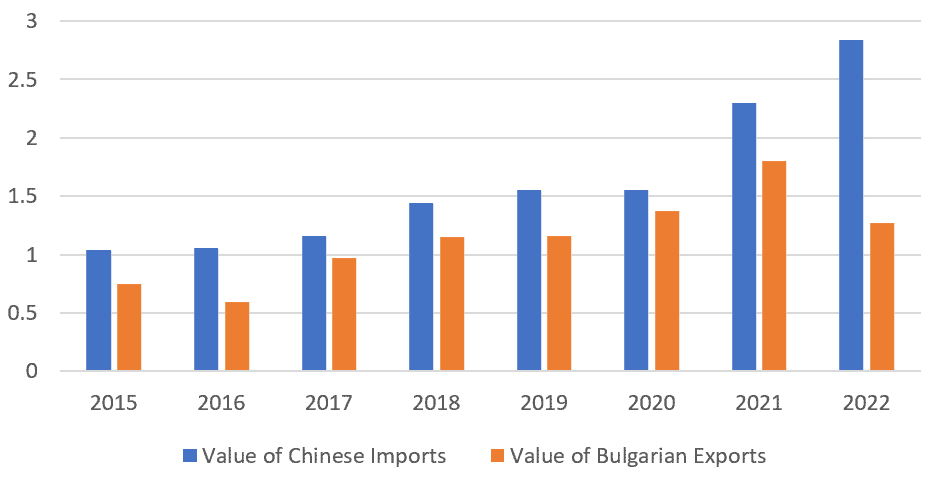

The dataset from the GAC–PRC (2023) is much more detailed and consistent than the one provided by the NSI. It contains yearly data for the entire 2015-2022 period, allowing one to track multiple trends. As Figure 1 (below) illustrates, during this period the total volume of Chinese exports to Bulgaria has increased from USD[6] 1.04b to 2.84b, while that of Bulgarian exports to China only started at USD 748 million in 2015, reached a peak of USD 1.8 billion in 2021 and subsequently dropped down to USD 1.27 billion in 2022, resulting in a record-level imbalance of USD 1.57 billion for the same year.

Figure 1. Value of Bilateral Trade between Bulgaria and China, USD billion (2015-2022)

Source: Created by the author; based on data from the GAC–PRC (2023).

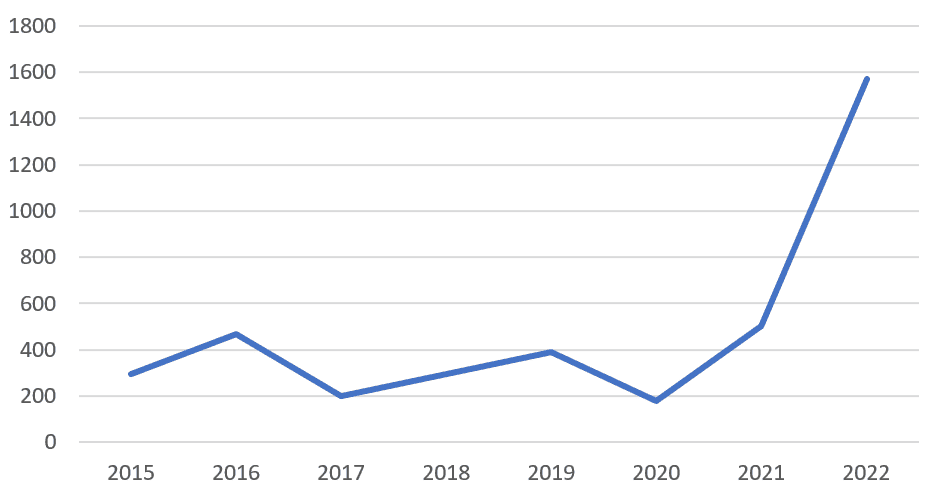

As indicated in Figure 2, from 2015 to 2021 the trade imbalance between Bulgaria and China previously fluctuated between USD 200 million and USD 502 million. The trade composition of Bulgarian exports to China should be a cause of concern for the Bulgarian government and business community. As Table 1 below indicates, more than half of the total value of exported products has consistently been in primary sector categories, with copper accounting for between 42% and 61% of the yearly totals from 2015 to 2021.

Figure 2. Value of Trade Imbalance between Bulgaria and China, USD billion (2015-2022)

Source: Created by the author; based on data from the GAC–PRC (2023).

From 2021 to 2022, the value of copper exports to China decreased by USD 523.1 million, from USD 777.1 million to USD 254 million. This sudden drop accounts for 48.9% of the sudden 2022 rise in the bilateral trade imbalance discussed above. Although the reason for it has not been publicly disclosed, it is most likely caused by a completed or interrupted long-term arrangement between Aurubis Bulgaria and its Chinese partners. This company is a part of the German conglomerate Aurubis and its Bulgarian subsidiary is currently the largest company in Bulgaria (Filipova, 2022); it operates a mining site near Pirdop and has traditionally signed stable multi-year contracts with Chinese partners such as China Minmetals (Dnevnik, 2009).

Table 1. Leading Bulgarian Exports to China, USD million and Percentage of the Total (2015-2022)

|

2015 |

395.45 (52.85%) |

N/A |

116.68 (15.59%) |

49.89 (6.67%) |

13.55 (1.81%) |

29.11 (3.89%) |

2.93 (3.20%) |

39.10 (5.23%) |

12.05 (1.61%) |

3.52 (0.47%) |

|

2016 |

247.01 (41.86%) |

0.009 (0.002%) |

118.13 (20.02%) |

48.42 (8.21%) |

19.25 (3.26%) |

27.30 (4.63%) |

32.37 (5.49%) |

0.20 (0.03%) |

19.45 (3.30%) |

6.74 (1.14%) |

|

2017 |

590.03 (60.88%) |

0.30 (0.003%) |

75.83 (3.82%) |

69.92 (7.21%) |

22.25 (2.30%) |

36.34 (3.75%) |

37.81 (3.90%) |

0.15 (0.02%) |

26.72 (2.76%) |

10.76 (1.11%) |

|

2018 |

696.75 (60.78%) |

0.38 (0.003%) |

79.17 (6.91%) |

82.95 (7.24%) |

28.25 (2.46%) |

46.08 (4.02%) |

41.43 (3.61%) |

0.33 (0.003%) |

39.90 (3.48%) |

20.31 (1.77%) |

|

2019 |

645.433 (55.44%) |

0.91 (0,08%) |

68.52 (5.89%) |

91.60 (7.87%) |

43.58 (3.74%) |

51.72 (4.44%) |

47.63 (4.09%) |

0.92 (0.08%) |

45.96 (3.95%) |

32.42 (2.78%) |

|

2020 |

739.03 (53.91%) |

14.68 (1.07%) |

47.48 (3.46%) |

110.89 (8.09%) |

72.85 (5.31%) |

46.27 (3.38%) |

42.13 (3.07%) |

52.70 (4.35%) |

57.12 (4.17%) |

35.10 (2.56%) |

|

2021 |

777.10 (43.21%) |

99.32 (5.52%) |

182.31 (10.14%) |

144.97 (8.06%) |

112.76 (6.27%) |

73.37 (4.08%) |

61.24 (3.40%) |

44.72 (2.49%) |

66.87 (3.72%) |

47.70 (2.71%) |

|

2022 |

254.00 (19.94%) |

200.13 (15.72%) |

156.17 (12.26%) |

149.71 (11.76%) |

96.83 (7.60%) |

57.21 (4.49%) |

54.85 (4.31%) |

50.07 (3.93%) |

47.88 (3.76%) |

38.96 (3.06%) |

|

Product |

Copper and articles thereof |

Residues from the food industries |

Ores, slag and ash |

Electrical machinery and parts thereof |

Use-specific apparatus (e.g. optical, measuring) |

Men’s or boys’ overcoats and jackets |

Nuclear reactors, machinery, and parts |

Cereals |

Salt, sulphur, plastering materials, cement, etc. |

Non-railway vehicles and parts thereof |

Source: Created by the author; based on data from the GAC–PRC (2023). All category descriptors have been shortened by the author to improve readability. Since the fluctuation in many types of Bulgarian exports is highly dynamic, the table only shows those product categories which have accounted for over 3% of the total in any year during the 2015-2022 period.

Another notable change in the structure of Bulgarian exports is the rising importance of food industry residues from non-existent in 2015 to USD 200.13 million, accounting for 15.72% of the total in 2022. It is difficult to assess the long-term implications of this shift; on one hand, it helps to diversify the export mix and indicates that Bulgarian agricultural exporters have found new buyers; on the other, this is yet another increase in the sales of low-value added goods from the primary sector. A more positive development is the considerable increase of export value in two categories of industrially-manufactured products. The first one is electrical machinery and parts thereof, which now take up USD 156.17 million, or 11.76% of the total, and the second one is use-specific apparatus, accounting for USD 96.83 million, or 7.60% of total exports. Although Bulgarian exports to China are becoming more diversified, the speed at which different product categories increase in volume and value is insufficient to effectively balance out vis-à-vis the rise of Chinese exports to Bulgaria.

Chinese exports to Bulgaria primarily consist of industrially-manufactured products from the secondary sector. As Table 2 indicates, the value of exports in five of the seven leading product categories have grown at a steady rate between 2015 and 2022; the largest category which exemplifies this trend during said period is the export of nuclear reactors, machinery and parts thereof, which increased from USD 210.58 million, accounting for 20.18% of total exports, to USD 505.63 million, accounting for 17.78% of total Chinese exports to Bulgaria. Other, smaller categories which saw a similarly steady increase include furniture, bedding and similar products and non-railway vehicles and parts thereof, among others. In contrast to them, from 2015 to 2022 exports in the product category of electrical machinery and parts thereof increased from USD 171.58 million and 16.45% of total export value to USD 768.54 million, which accounts for 27.03% of total export value, making it the leading category of Chinese exports to Bulgaria. In contrast to the increase in Bulgarian exports of primary sector products to China discussed above, China is selling more industrially manufactured goods to Bulgaria and thus, it receives not only a quantitative but also a qualitative benefit from the bilateral trade relationship.

The destinations of Bulgarian exports and the origin of Chinese ones reveal partial (but still important) insight on the relative rise and fall in the importance of specific cities and provinces in the bilateral economic relationship. Disregarding a short-lived dip in 2016 and a brief rise in 2021, the value of Bulgarian products imported through Shanghai has remained relatively stable over time, fluctuating between USD 152 million and USD 267 million.

Table 2. Leading Chinese Exports to Bulgaria, USD million and Percentage of the Total (2015-2022)

|

Nuclear reactors, machinery, and parts thereof |

210.58 (20.18%) |

206.14 (19.51%) |

236.68 (20.25%) |

277.52 (19.27%) |

297.20 (19.12%) |

304.30 (19.67%) |

459.32 (19.97%) |

505.63 (17.78%) |

|

Electrical machinery and parts thereof |

171.58 (16.45%) |

179.92 (17.03%) |

218.62 (18.70%) |

304.56 (21.15%) |

295.39 (19.00%) |

319.10 (20.63%) |

555.83 (24.16%) |

768.54 (27.03%) |

|

Furniture; bedding and similar products |

66.39 (6.36%) |

51.91 (4.91%) |

46.01 (3.94%) |

58.63 (4.07%) |

84.33 (5.42%) |

104.06 (6.73%) |

165.05 (7.18%) |

172.77 (6.08%) |

|

Organic chemicals |

61.65 (5.91%) |

60.18 (5.70%) |

60.31 (5.16%) |

62.22 (4.32%) |

49.25 (3.17%) |

56.75 (3.67%) |

60.48 (2.63%) |

63.23 (2.22%) |

|

Non-railway vehicles and parts thereof |

61.14 (5.86%) |

68.47 (6.48%) |

54.13 (4.63%) |

79.33 (5.51%) |

89.86 (5.78%) |

86.03 (5.56%) |

143.46 (6.24%) |

172.20 (6.06%) |

|

Plastics and articles thereof |

36.62 (3.51%) |

36.83 (3.49%) |

37.91 (3.24%) |

52.30 (3.63%) |

50.01 (3.22%) |

50.63 (3.27%) |

86.77 (3.77%) |

123.47 (4.34%) |

|

Use-specific apparatus (optical, measuring, etc.) |

22.28 (2.14%) |

32.11 (3.04%) |

39.17 (3.35%) |

48.42 (3.36%) |

56.64 (3.64) |

61.99 (4.01%) |

84.20 (3.66%) |

95.42 (3.36%) |

|

Year |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

Source: Created by the author; based on data from the GAC–PRC (2023). All category descriptors have been shortened by the author to improve readability. Since the structure of Chinese exports is relatively stable, the table only shows product categories which accounted for over 3% of total Chinese exports to Bulgaria in most years during the 2015-2022 period.

The importance of Beijing rose dramatically during the 2017-2021 period, briefly reaching a record high of USD 637.70 million of Bulgarian imports in 2020, when it accounted for 46.55% of total Bulgarian imports to China. It is worth mentioning that this was during the last mandate of the Commercial Counselor to Beijing Stoyan Nikolov which ended in early 2022, leaving the position vacant since then. After his departure, in 2022 the value of Bulgarian exports to Beijing fell over six times to USD 92.88 million, which accounts for 7.31% of the total. Although Bulgarian exports to Jiangsu and Liaoning have increased considerably, as Table 4 reveals, the trade balance of Bulgaria with these two provinces is very different; as of 2022, it has a deficit of USD 335.2 million vis-à-vis Jiangsu and a surplus of USD 64.39 million vis-à-vis Liaoning.

The customs points of entry and the origin of shipment of goods traded between Bulgaria and China do not necessarily indicate where their final consumers are located. However, it is important from a strategic perspective since it can provide important context for designing strategic action regarding the provincial government authorities and organizations that could be approached to offer support in terms of opportunities to place more Bulgarian products on the Chinese market.

First, the data indicates that there is a good basis to begin a deeper dialogue with Jiangsu province to discuss the potential of increasing the amount of Bulgarian goods imported there, as this area of China accounts for an increasingly large amount of the trade deficit that Sofia is racking up.

Table 3. Most Popular Destinations (Customs Points of Entry) of Bulgarian Exports to China, USD Million and Percentage of the Total (2015-2022)

|

Jiangsu |

130.45 (12.50) |

128.64 (12.18) |

147.76 (12.64%) |

188.44 (13.08%) |

222.99 (14.34%) |

252.85 (16.34%) |

356.76 (15.51%) |

448.41 (15.77%) |

|

Shanghai |

57.85 (5.55%) |

61.39 (5.81%) |

70.78 (6.05%) |

90.60 (6.29%) |

103.68 (6.67%) |

115.81 (7.49%) |

149.98 (6.52) |

174.70 (6.14%) |

|

Tianjin |

25.04 (2.40%) |

29.63 (2.80%) |

24.12 (2.06%) |

30.86 (2.14%) |

38.15 (2.45%) |

32.61 (2.11%) |

43.13 (1.87%) |

43.16 (1.52%) |

|

Hebei |

16.70 (1.60%) |

16.00 (1.51%) |

19.38 (1.66%) |

21.85 (1.52%) |

22.83 (1.47%) |

21.58 (1.39%) |

31.51 (1.37%) |

38.24 (1.34%) |

|

Liaoning |

12.38 (1.19%) |

14.39 (1.36%) |

17.44 (1.49%) |

18.01 (1.25%) |

15.71 (1.01%) |

13.46 (0.87%) |

18.33 (0.80%) |

17.47 (0.61%) |

|

Beijing |

10.38 (0.99%) |

8.51 (0.80%) |

20.99 (1.80%) |

42.71 (2.97%) |

46.26 (2.98%) |

61.00 (3.94%) |

103.24 (4.49%) |

107.60 (3.78%) |

|

Province or City |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

Source: Created by the author; based on data from the GAC–PRC (2023). Only provinces and cities that have consistently received over USD 3m of imports per year from Bulgaria are listed.

Table 4. Most Popular Points of Origin (Shipment) of Chinese Exports to Bulgaria, USD Million and Percentage of the Total (2015-2022)

|

Jiangsu |

130.45 (12.50) |

128.64 (12.18) |

147.76 (12.64%) |

188.44 (13.08%) |

222.99 (14.34%) |

252.85 (16.34%) |

356.76 (15.51%) |

448.41 (15.77%) |

|

Shanghai |

57.85 (5.55%) |

61.39 (5.81%) |

70.78 (6.05%) |

90.60 (6.29%) |

103.68 (6.67%) |

115.81 (7.49%) |

149.98 (6.52) |

174.70 (6.14%) |

|

Tianjin |

25.04 (2.40%) |

29.63 (2.80%) |

24.12 (2.06%) |

30.86 (2.14%) |

38.15 (2.45%) |

32.61 (2.11%) |

43.13 (1.87%) |

43.16 (1.52%) |

|

Hebei |

16.70 (1.60%) |

16.00 (1.51%) |

19.38 (1.66%) |

21.85 (1.52%) |

22.83 (1.47%) |

21.58 (1.39%) |

31.51 (1.37%) |

38.24 (1.34%) |

|

Liaoning |

12.38 (1.19%) |

14.39 (1.36%) |

17.44 (1.49%) |

18.01 (1.25%) |

15.71 (1.01%) |

13.46 (0.87%) |

18.33 (0.80%) |

17.47 (0.61%) |

|

Beijing |

10.38 (0.99%) |

8.51 (0.80%) |

20.99 (1.80%) |

42.71 (2.97%) |

46.26 (2.98%) |

61.00 (3.94%) |

103.24 (4.49%) |

107.60 (3.78%) |

|

Province or City |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

Source: Created by the author; based on data from the GAC–PRC (2023). Only provinces and cities that have consistently accounted for over USD 10m of exports per year are listed.

Second, the numbers suggest that it is imperative for the Bulgarian government to appoint a Commercial Counselor in Beijing. Third, it is striking that Bulgaria primarily trades with a small number of Chinese provinces and missed out on deeper economic exchange with the trade hubs in Guangdong, where many already countries have trade representatives, including officials and chapter chairs of chambers of commerce.

Fourth, to seek receiving more favorable treatment, Bulgarian officials and businessmen should seek to establish deeper contacts with provinces that currently have little trade with Bulgaria, such as Sichuan or Shaanxi, where the EU-China freight train strategically stops to offload imported goods in order to increase their connectivity with the world (Jakóbowski, Popławski and Kaczmarski, 2018). Chinese provinces are competing for deepening their internationalization as well as attracting foreign companies to establish their local operations there (Wong, 2018); while wealthy provinces such as Jiangsu have little incentive to provide pro-active assistance to Bulgaria, the governments of lesser-known provinces are often happy to help companies, officials and business organizations to engage with them. This insight should inform the general approach of Bulgaria towards trade relations with China and the government and business community should have a coherent approach in terms of their target provinces for further engagement.

Finally, one large potential obstacle to deepening Bulgarian exports to China is the issuance of trade protocols for plant and animal products. As of 2015, there were only three types of Bulgarian products which were certified to be imported in China while 24 others were pending (United Business Clubs, 2016); by the end of 2022, only 14 were left pending and ten types of products received protocols, namely: fish and fish products, alfalfa, corn, dairy products, feed and feed additives, sunflower meal, Distiller’s dried grains with solubles (DDGS), honey, peeled sunflower, as well as tobacco (Kandilarov, 2022). Notable product categories which are not yet certified for import include fruits and vegetables as well as chicken meat.

It is imperative for the Bulgarian government and for ulgarian trade officials in China to maximize their efforts for the issuance of trade protocols. This is a complex task which might require a certain amount of “lobbying” or making the Bulgarian case to Chinese officials; generally speaking, the most effective ways to do this is through showing them that there are certain products of which Bulgaria can provide a large quantity, or which would be important to Chinese consumers. When neither of these two apply, it might be necessary to either use the method of repeated trial and be persistent, or attempt to recruit supporters from Chinese political circles, who could vouch for Bulgaria to their colleagues. If Bulgarian government and business representatives can effectively mobilize their efforts to engage with lesser-known provinces, officials there would be much more likely and willing to help. However, this would be dependent on the presence of a coherent strategy and its execution, while there is no evidence of this from the Bulgarian side at present.

4. Business Relations

In addition to the trade trends discussed above, it is also important to understand the role of specific companies in bilateral economic relations between Bulgaria and China. During most trade fairs and presentations of Bulgaria in China, the most actively advertised Bulgarian products include rose cosmetics, food, and drinks. While these retail products do not amount to a large volume that can potentially repair the trade imbalance, they have a strategic importance due to their role as a means of introducing large groups of Chinese consumers to Bulgaria.

The reason for the promotion of rose-based cosmetic products is that they are based on oil from rosa damascena, a species which has been cultivated on an industrial scale in Bulgaria as its natural conditions are highly suitable to the plant (Antonova et al., 2019). The products of numerous Bulgarian rose cosmetics brands are sold mostly online in China. Brands such as Bulgarian Rose, Refan and Ecommat are available through retailers on some e-commerce platforms, while on others they operate their own stores in cooperation with local partners (see., e.g., JD, 2023; Taobao, 2023). These Bulgarian brands face severe competition from Chinese ones such as Pox Hero which is particularly popular on Kuaishou (2023) and sells cosmetics which are branded “Bulgarian” but are produced in Guangdong from the plant species rosa rugosa. There are dozens of similar Chinese brands such as Yuranm, Erfan and Yfooli, among others. All of them offer a competitive price as well as attractive packaging, and despite the lack of official data, it is highly likely that they make considerably larger sales than genuine Bulgarian companies.

Few Bulgarian brands of food and drinks are available in China and most of them are available through a WeChat shop named The Balkan Deli[7]. It offers a variety of fruit juices from Florina, which are also available in supermarkets chains such as BHG Market Place. The Balkan Deli also sells more specific products such as the traditional tomato-and-pepper sauce “liutenica” by Philicon and wines from Chateau Burgozone and Midalidare. However, even in cases when they receive greater exposure, e.g., in chain stores or e-commerce platforms, these types of products continue to remain niche, as do the Bulgarian rose-based cosmetics discussed above. There are numerous reasons for this, including small production quantities, low market entry budget and know-how to position themselves on the Chinese market, as well as limited capacity to use digital technologies and localize their campaigns, or convince a large local partner to cooperate and bear the marketing expenses. Furthermore, Chinese consumers lack a general awareness of Bulgaria which makes it difficult to rely on nation branding, while other more minor issues such as unattractive packaging also limit the appeal of many Bulgarian brands.

There are products associated with Bulgaria which have been successfully branded and sold across China. One such product is yoghurt, which is a hallmark of Bulgaria as one of the two lactic acid bacterial species needed to make it is a subspecies of lactobacillus delbrueckii that has been named “bulgaricus”, after the country (El Kafisi, Binesse, Loux et al., 2014). The most popular Bulgarian-branded yoghurt is sold under the label Momchilovtsi, which is the name of a village in the Rhodope mountains. It is not produced with the special bacteria that Bulgaria is known for, as Chinese consumers prefer a watered down, sweeter yoghurt that they can drink, rather than the thick and buttery yoghurt which is traditionally made in Bulgaria.

The Momchilovtsi brand was created by the Chinese company Bright Dairy & Food Company and it uses advertisements shot in the eponymous village. In 2008, representatives from the company visited the village of Momchilovtsi for the first time; later, they signed a joint agreement with the Mayor’s office and with a local tour operator for the right to use the brand of the village (Terzieva, 2016). On one hand, this has helped to improve awareness of Bulgaria in China and led to a small increase in Chinese tourists to Momchilovtsi. On the other hand, the Bulgarian economy receives little benefit from this branding deal as the bulk of profit remains for Bright Dairy & Food Company, which reportedly made sales of over USD 100 million in 2017 (Georgieva, 2017), and has since further expanded its product range. While partnerships with large Chinese companies are possible and could be beneficial, they should ideally include a Bulgarian company involved in the business and production as well.

More recently, the Bulgarian company By Far successfully entered the Chinese market, selling a considerable quantity of women’s handbags, shoes, and accessories. These products are positioned at the lower end of the luxury goods market, and they are best known for their creative modern design as well as for their high quality. The company does not brand itself as a purely “Bulgarian” company, but rather insists that it was developed “between Sofia, London, and Sydney” (By Far, 2023). This international appeal is one of many factors that has helped it to establish a market presence more quickly; in terms of its approach to the Chinese market, other reasons for its success include high-quality offerings, clear price positioning, modern vision with a focus on innovation, strong presence on online platforms and excellent use of livestreaming and product placement on the home pages of online platforms. This combination has allowed By Far to thrive and appeal to young Chinese urban consumers who are much more willing to purchase high value-added products. There are many good practices to be learned from this case which are beyond the scope of this article, so it is vital for both Bulgarian companies and trade promotion officials to explore it further in detail.

Chinese investment in Bulgaria is sporadic and takes place on a relatively small scale. Many analysts and media reports make the generic statement that it accounts for “less than 1%” (e.g., Harper, 2021; Novini 247, 2022) of total FDI in Bulgaria because there is no exact official data on the gross amount of Chinese investment per year. The Bulgarian National Bank (BNB) only releases information about the net balance of FDI (inflow minus outflow of capital classified as investment) in Bulgaria from each country per year. As Table 5 indicates, the average contribution of Chinese investment to the Bulgarian economy during the 2015-2022 period is EUR 7.05 million per year, a number which would theoretically account for around 0.3% of the yearly net investment inflow in recent years.

A considerable part of Chinese investment in Bulgaria is in agriculture and some of the ongoing companies which continue to operate began before 2015 but continued to develop within the 2015-2022 period. Perhaps the most notable influx of Chinese capital in Bulgarian agriculture has come through Tianjin Farm Cultivation Group Company Bulgaria (operating mainly around Parvomai), which is owned by the Chinese entity Tianjin Food Group. In 2021, the assets held by the Bulgarian company were worth EUR 40.5 million (before depreciation). Another Chinese-owned agricultural company in Bulgaria is Bulgaria Tianshihong Feeding (operating primarily around Dobrich), 95.8% of which is owned by Tianjin China and Europe Agro-Pastoral International Trade. The Bulgarian entity has reported the possession of assets worth EUR 8.7 million (Registry Agency of Bulgaria, 2023).

Curiously, some reports misidentify certain investments as Chinese-owned; for instance, one such case is that of the vine growing company Terra Land which Shopov (2022) has claimed to be a recipient of EUR 8 million of “Chinese” investment. In reality, the company’s sole owner is Zheng Zhong (Ibid.), a Bulgarian businessman of Chinese heritage (and native speaker of Bulgarian) who appears as a frequent guest and analyst of international and business affairs on various media outlets (e.g., BTV, 2021a). These types of misunderstandings contribute to the difficulty of collecting credible data on economic engagement between Bulgaria and China.

Table 5. Chinese FDI as a Percentage of Total FDI in Bulgaria, USD Million and Percentage of the Total (2015-2022)

|

Net Change in Chinese FDI |

29.5 |

-20.1 |

0.8 |

3.7 |

20.3 |

-6.0 |

7.6 |

20.6 |

|

Net Change in Total FDI |

2485.9 |

811.1 |

1720.5 |

1583.2 |

2012.6 |

2617.9 |

2524.3 |

2594.9 |

|

Increase in Chinese FDI as a percentage |

1.19% |

N/A |

0.05% |

0.23% |

1.01% |

N/A |

0.30% |

0.79% |

|

Year |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

Source: Created by the author; based on data from the Bulgarian National Bank (2023).

There are two notable cases of investments in Bulgaria by European subsidiaries of Chinese conglomerates. The first one is COFCO International Bulgaria, which is owned by the Dutch company CIL Agri Enterprise, which is registered under the name of the overseas agriculture business platform for COFCO Corporation, China’s largest food and agriculture company. The Bulgarian company has declared assets worth EUR 62.8 million (Registry Agency of Bulgaria, 2023).

The second case is that of Amer Sports Bulgaria, which is owned by an Austrian-registered company, which is part of the formerly-Finnish sportswear group Amer Sports Corporation, which was acquired in 2018 by a Chinese consortium comprising ANTA Sports, FountainVest Partners, Anamered Investments and Tencent (Wang, 2018). Like COFCO International Bulgaria, Amer Sports Bulgaria holds assets worth EUR 23.5 million (Registry Agency of Bulgaria, 2023). In both cases, these companies have developed production facilities in Bulgaria, they make large investments in developing them and are set to provide employment and opportunities for cooperation with local partners for decades to come. Although they are not well-known among the general public, these are the types of investment that offer considerable value to the Bulgarian economy.

Among the general public, there is much greater awareness about big Chinese tech companies that have entered the Bulgarian market. The most prominent case is that of Huawei; as of 2022, its subsidiary Huawei Technologies Bulgaria holds assets worth EUR 52.5 million (Ibid.) and it strives to publicly showcase its positive contribution to the Bulgarian economy. In a report commissioned to Oxford Economics (2020), Huawei was estimated to have contributed EUR 31 million to Bulgaria’s total GDP, while also creating 1,100 jobs during the 2015-2019 period, although only 100 of these jobs were direct employment by the company, and the remaining 1,000 were “indirect” or “induced”. Huawei strives to receive positive press coverage (although much of it in the form of paid posts, e.g., see Kapital, 2022 and 2023), and it supports various organizations and initiatives, such as the For Our Children Foundation (2022) and the Seeds for the Future program (Kapital, 2022). Other Chinese big tech companies such as ZTE and Xiaomi also have subsidiaries in Bulgaria, although they operate on a smaller scale. While these developments are generally positive, Chinese tech companies in Bulgaria primarily operate as retailer businesses or as service and equipment providers targeting both the mass consumer market and larger commercial deals. From an economic standpoint, the Bulgarian government should instead incentivize them to establish large production facilities in the country and commit larger amounts of investment while creating many more direct employment opportunities.

Recently, various other Chinese companies have also begun to establish operations in Bulgaria, albeit on a smaller scale. Haval (2022) has recently begun to offer its cars on the Bulgarian market as its brand owner, Great Wall Motor Group, has a previous history of attempting to operate in Bulgaria. From 2012 to 2017, Litex Motors operated a production facility in Lovech which was built with funding from the now-defunct Corporate Trade Bank, while Great Wall Motor Group served as a technology provider at the time (Granitska and Nikolov, 2017). Now, the company is seeking to re-enter the Bulgarian market with help from the prominent businessman Anton Donchev who has declared their intentions to introduce several brands to Bulgaria, to potentially establish a production line of electrical vehicles and to facilitate the sales of more electric public transport buses to the country (China Radio International, 2022).

More recently, Moutai has decided to establish a small presence in Bulgaria by hiring a small team of three members to operate a Moutai Center, sponsor and support various events across the country (Hanes, 2022). The greatest economic gains for Bulgaria from the entry of these big companies would be if they would commit to establishing factories in the country or develop large-scale commercial operations there with the aim of building their European or regional headquarters in Bulgaria. This would be much easier if there was a track record of some successful cases to show, or a strategic effort to position Bulgaria as a manufacturing powerhouse or a major logistics hub; such considerations should be factored in the design of a national strategy towards China.

At a more granular level, individuals and business organizations play an important role in shaping business relations between Bulgarian and Chinese companies. For instance, Krastio Belev manages the Bulgarian-Chinese Business Development Association (China Radio International, 2017), although its activity has slowed down considerably in recent years. Currently, the most prominent facilitator of economic engagement between Bulgaria and China is Latchezar Dinev (Yordanova, 2023) who chairs the Bulgaria China Chamber of Commerce and Industry (BCCCI). Bulgarian government authorities should coordinate closely with these types of organizations because they are at the “front line” of facing potential Chinese trade partners and investors. They represent Bulgaria at trade expos, meet with companies on site across China, possess extensive experience and advisory expertise and have access to distributing relevant information or engaging human resources ranging from the younger generation of sinologists to experienced businesspeople.

5. Conclusion

In the current state of the global economy, China is poised to become an increasingly important economic partner of Bulgaria. This chapter has revealed the lack of coherence in the way that Bulgaria approaches this bilateral relationship, which results in missing opportunities for achieving more positive outcomes for Bulgaria and rebalancing the dynamics of its engagement with China. Its main body consists of three parts, analyzing the political, trade and business ties between the two countries from 2015 to 2022.

During this time period, there were several opportunities for meetings between Bulgarian and Chinese political leaders at the highest level. However, the approaches taken by the Prime Minister of Bulgaria as well as the demands he tends to present to the Chinese side have differed substantially from those which have been articulated by the Bulgarian President. A considerable number of the agreements signed by the Bulgarian Prime Minister in 2018 were about overly-ambitious projects, while some of the requests President Radev put forward to his counterpart in 2019 were insufficiently substantiated. Meanwhile, the capacity and extent of influence that the Bulgarian embassy has in Beijing lags behind that of the Chinese embassy in Sofia, and the prolonged absence of a Bulgarian ambassador in Beijing from 2021 to 2023 has sent a negative signal to the Chinese side. The political and diplomatic preconditions (e.g., historical willingness to engage, strategic partnership framework, participation in 16+1 and the BRI) for systematizing political engagement with China are present on the Bulgarian side but they are not purposefully used to achieve any targeted outcome.

Meanwhile, Bulgaria faces several challenges regarding its trade relations with China. First, there is considerable asymmetry in the type of goods traded: while Bulgaria primarily sells products from the primary sector, China exports products from the secondary sector with higher value added. Second, the trade deficit between Bulgaria and China has grown considerably from 2015 to 2022, and the current trade composition suggests that the imbalance could continue tip further in China’s favor, unless urgent action is taken. Third, on the Bulgarian side there appears to be little effort to conduct strategic engagement with relevant provincial governments with the aim of opening new markets or alleviating bureaucratic issues, benefitting from preferential policies, or promoting the national interest effectively through building strategic relationships with relevant officials. Specific instances of business relations between Bulgarian and Chinese companies in many cases exemplify and further explain the reasons for some of the issues that Bulgaria faces in terms of political and trade engagement. Bulgarian cosmetics, food and drinks have little recognition in China; a successful cooperation case on developing the yoghurt brand Momchilovtsi primarily generates profit for the Chinese side, while the wildly successful brand By Far is so far a standalone case, rather than a model to be followed by others. The general level of investment in Bulgaria is low and much of it is in agriculture, or in tech companies that serve as retailers and service providers. The case of Amer Sport reveals that the successful establishment and management of production facilities by Chinese-owned conglomerates in Bulgaria is possible and other companies should be incentivized and encouraged to view Bulgaria as a manufacturing or logistics hub, and a country that has various forms of value to offer to foreign investors.

While the challenges that Bulgaria faces in its relations with China have been built up over time, they are not insurmountable. There is sufficient flexibility in the current framework of Bulgaria-China relations to adjust the mode of political, trade and corporate relations between the two sides and improve the outcomes for Bulgaria. This requires the design and implementation of a Bulgarian national strategy for bilateral engagement with China. In lieu of presenting further general comments, this conclusion ends with ten specific recommendations for necessary steps to maximize the benefit Bulgaria obtains from engagement with China. To this end, the Bulgarian government should:

1. Task specific officials to compile and maintain a clear record of data related to economic engagement between Bulgaria and China in order to effectively inform strategic and policy decisions.

2. Set intended outcomes of Bulgaria’s bilateral relations with China and establish working coordination mechanisms between key actors, including ministries, agencies as well as the teams of the Prime Minister and the President’s Office.

3. Define the economic interest of Bulgaria vis-à-vis China in terms of specific aims related to the bilateral trade balance, the types of products that Bulgaria seeks to export and the types of investment it seeks to receive.

4. Reach agreement regarding said economic interest with the business community and either establish an initiative for maintaining regular coordination and communication with them, or entrust a specific organization (e.g., chamber of commerce) to do this.

5. Prepare realistic proposals for joint projects with China which are in line with the general economic development strategy of Bulgaria and with the perception and image that the country seeks to maintain in China.

6. Attend leader meetings at the highest level with the aim of signing concrete agreements for the realization of said projects; leverage the pressure that Chinese officials have to secure good publicity and use these opportunities to reach agreements which have a clear benefit for Bulgaria.

7. Increase the number of Bulgarian officials who are dispatched to China at the Embassy to Beijing and appoint at least two more commercial counselors to the provinces of Guangdong and Chengdu or similar locations.

8. Provide practical training to all Bulgarian officials in China and actively encourage them to employ non-traditional strategies (e.g., deeper engagement with provincial governments) to counterbalance asymmetric aspects of the bilateral relationship.

9. Engage all available institutional and human resources which are available (e.g., EU SME Centre, the EU-China Chamber of Commerce and Chinese CCPITs, among others); motivate more Bulgarians located in China or studying Chinese to get involved in helping achieve national aims.

10. Incentivize Bulgarian officials and relevant organizations to be pro-active in engaging with their counterparts; ensure that not all bilateral cooperation projects are proposed and initiated by the Chinese side.

Endnotes

-

The initiative was initially referred to as the One Belt One Road (OBOR). ↑

-

The Chinese term is guojia zhuxi, which literally means “Secretary of the State” but it is often translated to English as “President”. In Chinese politics, this title is less important than that of “Secretary General of the Chinese Communist Party” and that of “Chairman of the Central Military Commission”. A leader that holds all three simultaneously, such as Xi Jinping, is informally referred to as a “Paramount Leader”. ↑

-

The acronym “China-CEEC” stands for “China-Central and Eastern European Countries”. The initiative for cooperation between China and CEEC is also known as “16+1”. ↑

-

Zhang QIngli served as the first-ranked Vice-Chairman of the 13th National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) from 2017 to 2022. ↑

-

Li Zhanshu served as the Chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress from 2018 to 2023. ↑

-

Note that data from the NSI is reported in EUR, while data from the GAC-PRC is reported in USD. ↑

-

At the time of writing this chapter in mid-2023, The Balkan Deli online shop (WeChat “mini-app”) appears to be closed due to violating the rules of WeChat. ↑

Bibliography

24 Chasa (2023a) “Kitaiskata narodna republika – sutrudnichestvo na osnovata na vzaimoizgodnoto razvitie” (“The People’s Republic of China – cooperation on the basis of mutually beneficial development”), 5 August. Available from: https://www.24chasa.bg/mezhdunarodni/article/15075623 (Accessed on 22 August 2023).

24 Chasa (2023b) “Noviyat korab na Parahodstvo ‘Bulgarski morsi flot’ nosi imeto ‘Slavyanka’” (The New Ship of Parahodstvo Bulgarian Maritime Fleet Has the Name Slavyanka), 2 August. Available from: https://www.24chasa.bg/bulgaria/article/15044003 (Accessed on 24 August 2023).

Agri BG (2018) “Zayavka ot Kitai za 10,000 tona tutu not Bulgaria”, 10 July. Available from: https://agri.bg/novini/zayavka-ot-kitay-za-10-000-tona-tyutyun-ot-balgariya (Accessed 16 June 2023).

Antonova, D. V., Medarska, Y. N., Stoyanova, A. S., Nenov, N. S., Slavov, A. M. Antonov, L. M. (2021) “Chemical Profile and Sensory Evaluation of Bulgarian Rose (Rosa Damascena Mill.) Aroma products, Isolated by Different Techniques”, Journal of Essential Oil Research 33(2), pp. 171-181.

Boni, F. (2022) “Strategic Partnerships and China’s Diplomacy in Europe: Insights from Italy”, The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 0(0), pp. 1-18.

BTV (2021a) “Tsun Tson – edin kitaec, koito priema Bulgaria za svoya vtora rodina” (“Zheng Zhong – A Chinese Man who Accepted Bulgaria as his Second Motherland”), 11 July 2021. Available from: https://btvnovinite.bg/predavania/tazi-sabota-i-nedelia/can-con-edin-kitaec-kojto-priema-balgarija-za-svoja-vtora-rodina.html (Accessed on 3 May 2023).

BTV (2021b) “Vizhte koi sa 8-te nai-golemi kreditopoluchateli ot BBR” (“See Who are the Eight Largest Lenders from the BDB”), 17 May. Available from: https://btvnovinite.bg/bulgaria/vizhte-koi-sa-8-te-naj-golemi-kreditopoluchateli-ot-bbr.html (Accessed on 18 June 2023).

Bulgaria on Air (2018) “Sled vizitata na Li Kutsiyan: Zashto Kitai iska da investira v Bulgaria?” (“After the Visit of Li Keqiang: Why Does China Want to Invest in Bulgaria?”), 9 July. Available from: https://www.bgonair.bg/a/108-video/156702-sled-vizitata-na-li-katsyan-zashto-kitay-iska-da-investira-v-balgariya (Accessed on 20 July 2023).

Bulgarian Development Bank (2022) “Godishni otcheti za 2021 godina” (Yearly Reports for the Year 2021). Available from: https://bbr.bg/bg/publichna-informaciya/finansovi-otcheti/godishni-otcheti-za-2021-godina/ (Accessed on 3 May 2023).

Bulgarian Development Bank (2023) “Kitayska banka za razvitie” (“Chinese Development Bank”). Available from: https://bbr.bg/bg/mezhdunarodni-partnori/kitajska-banka-za-razvitie/ (Accessed on 15 June 2023)

By Far (2023) Available from: https://www.byfar.com/ (Accessed on 22 July 2022).

Chen, Ying (2020) “Kitaiskata literature v Bulgaria I Bulgarskata literatura v Kitai – prevodi I izdavane” (“Chinese Literature in Bulgaria and Bulgarian Literature in China – Translations and Publishing”), Orbis Linguarum, 4, pp. 110-113.

Wu, J. and Zhang, Y. (2013) “Xi proposes a ‘new Silk Road’ with Central Asia”, China Daily (2013), 9 August. Available from: https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2013xivisitcenterasia/2013-09/08/content_16952228.htm (Accessed 6 June 2023).

China Radio International (2017) “Interviu na Krastio Belev ot Bulgaro-kitaiskata asociaciya za biznes razvitie” (“Interview with Krastio Belev from the Bulgarian Chinese Business Development Association”), 15 June 2017. Available from: https://bulgarian.cri.cn/1041/2017/06/15/1s168597.htm (Accessed on 5 May 2023).

China Radio International (2020) “V Sofia zapochva izgrazhdaneto na bulgaro-kitaiski centur za inovacii” (“The Establishment of a Bulgaria-China Center for Innovation Begins in Sofia”), 6 November. Available from: https://bulgarian.cri.cn/1081/2020/06/11/243s201976.htm (Accessed on 18 June 2023).

China Radio International (2022) “Kitaiskiya avtomobilen sektor – novi tehnologii I sutrudnichestvo s Bulgaria – g-n. Anton Donchev za KMG” (“The Chinese Automotive Sector – New Technologies and Cooperation with Bulgaria – Mr. Anton Donchev for the Chinese Media Group”), 31 August 2022. Available from: https://bulgarian.cri.cn/2022/08/31/ARTIBFnUpKvCNZPI93W1vv5H220831.shtml (Accessed on 14 August 2023).

Georgieva (2017) “Kitayskiyat put na Momchilovtsi” (“The Chinese Road of Momchilovtsi”), Kapital, 23 September. Available from: https://www.capital.bg/biznes/predpriemach/2017/09/23/3045732_kitaiskiiat_put_na_momchilovci/ (Accessed on 11 June 2023).

Dnevnik (2009) “Medodobivniyat kombinat v Pirdop skliuchi dogovor za iznos za Kitai” (“The Copper Mining Facility in Pirdop Signed a Contract for Export to China”), 15 October. Available from: https://www.dnevnik.bg/biznes/2009/10/15/800559_medodobivniiat_kombinat_v_pirdop_skljuchi_dogovor_za/ (Accessed on 5 July 2023).

El Kafsi, H., Binesse, J., Loux, V. et al. Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. lactis and ssp. bulgaricus: a chronicle of evolution in action. BMC Genomics 15, 407 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-15-407

Filipova, I. (2022) “‘Aurubis Bulgaria’ dobavya 100 mln. evro kum pechalbata si” (“‘Aurubis Bulgaria’ adds EUR 100 million to its profit”), Kapital, 21 December. Available from: https://www.capital.bg/biznes/promishlenost/2022/12/21/4431126_nai-goliamata_kompaniia_-_aurubis_bulgariia_dobavia/ (Accessed on 27 July 2023).

GAC–PRC – General Administration of Customs of the PRC (2023) Available from: http://stats.customs.gov.cn/ (Accessed on 26 June 2023).

Harper, J. (2021) “Opasni li sa kitaiskite investicii v iztochna Evropa?” (“Are Chinese investments in Eastern Europe Dangerous?”), DW, 19 August. Available from: https://www.dw.com/bg/българия-унгария-полша-опасни-ли-са-китайските-инвестиции-в-източна-европа/a-58903118 (Accessed on 22 July 2023).

For Our Children Foundation (2022) “Huawei Bulgaria donated technology and equipment to the new Academy for Social Learning and Development of the For Our Children Foundation”, 8 July. Available from: https://detebg.org/en/news/huawei-bulgaria-donated-technology-and-equipment-to-the-new-academy-for-social-learning-and-development-of-the-for-our-children-foundation/ (Accessed on 13 June 2023).

Granitska and Nikolov (2017) “Prikluchi tretiyat opit za zavod za koli v Bulgaria” (“The Third Attempt for a Car Factory in Bulgaria Ended”), 28 March. Available from: https://www.mediapool.bg/priklyuchi-tretiyat-opit-za-zavod-za-koli-v-bulgaria-news261957.html (Accessed on 18 July 2023).

Haval (2022) “Dva novi SUV modela HAVAL I elektricheskiyat ORA byaha predstaveni na Avtomobilen salon Sofia” (“Two New SUV Models from HAVAL the Electric Car ORA Were Presented at the Automobile Salon Sofia”), 3 June 2022. Available from: https://haval.bg/novini/автомобилен-салон-софия-нови-модели/ (Accessed on 18 July 2023).

Hanes, E. (2022) “Make an Event out of It! Marketing Moutai & Chinese Cultural Centers”, YouTube.com, 28 September. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rmsGcjqYoGQ (Accessed on 22 May 2023).

Hristova-Balkanska, I., Bobeva-Filipova, D., Peneva, T. and Kostadinov, A. (2022) Turgovsko-investicionnite otnosheniya Bulgaria-Kitai (Bulgaria-China Trade and Investment Relations), Plovdiv: Paisiy Hieldarski.

Kapital (2015) “Kitaiski firmi iskat da investirat v bulgarsko rozovo maslo i sirene” (“Chinese Companies Want to Invest in Bulgarian Rose Oil and Cheese”), 29 November. Available from: https://www.capital.bg/biznes/kompanii/2015/11/29/2658903_kitaiski_firmi_iskat_da_investirat_v_bulgarsko_rozovo/ (Accessed on 8 July 2023).

Kapital (2022) “Huawei otlichi bulgarski studenti po programata Seeds for the Future” (“Huawei Awarded Bulgarian Students through the Program Seeds for the Future”) 6 December. Available from: https://www.capital.bg/biznes/kompanii/2022/12/06/4423283_huawei_otlichi_bulgarski_studenti_po_programata_seeds/ (Accessed on 7 August 2023).

Kapital (2023) “Misiyata na Huawei e nikoi da ne ostane sam v erata na digitalnata transformaciya” (“The Mission of Huawei is Not to Have Anyone Left Alone in the Era of Digital Transformation”), 18 January. Available from: https://www.capital.bg/biznes/tehnologii_i_nauka/2023/01/18/4439225_misiiata_na_huawei_e_nikoi_da_ne_ostane_sam_v_erata_na/ (Accessed on 19 July 2023).

Jakóbowski, J., Popławski, K. and Kaczmarski, M. (2018) “The Silk Railroad – The EU-China Rail Connections: Background, Actors, Interests”, Ośrodek Studiów Wschodnich, Warsaw.

JD (2023) Available from: https://www.jd.com/ (Accessed on 27 August 2023).

Kandilarov, E. (2022) “Bulgaria Economy Briefing: Trade and Economic Relations between Bulgaria and China – Challenges”, China-CEE Institute, Weekly Briefing Vol. 56 (2). Available from: https://china-cee.eu/2022/11/20/bulgaria-economy-briefing-trade-and-economic-relations-between-bulgaria-and-china-challenges-and-opportunities/ (Accessed on 8 June 2023).

Kastner, S. L., and Saunders, P. C. (2012) “Is China a Status Quo or Revisionist State? Leadership Travel as an Empirical Indicator of Foreign Policy Priorities”, International Studies Quarterly, 56 (1), pp. 163–177.

Kuaishou (2023) Available from: https://www.kuaishou.com/ (Accessed on 16 August 2023).

Li, Q. and Ye, M. (2019), “China’s Emerging Partnership Network: What, Who, Where, When and Why”, International Trade, Politics and Development, 3 (2), pp. 66-81.

Lin, Wenshuang (2020) “Izmereniya na Prepodavaneto na Bulgarski Ezik v Kitai: Ezikovi Umeniya, Obshti Poznaniya i Interdisciplinarnost” (“Target Dimensions of Bulgarian Language Teaching in China: Language Skills, General Knowledge and Interdisciplinarity”), Orbis Linguarum, 18 (3) pp. 96-100.

Lin, F., Yan, W., & Wang, X. (2017) “The Impact of Africa – China’s Diplomatic Visits on Bilateral Trade. Scottish Journal of Political Economy”, 64 (3), pp. 310–326.

Maritsa (2015) “Kitaici opitaha da predzhobyat Boiko” (“The Chinese Tried to Search Boyko”), Maritsa, 28 November. Available from: https://www.marica.bg/svqt/kitajci-opitaha-da-predjobqt-bojko (Accessed on 18 July 2023).

Mediapool (2015) “Borisov podkrepya ideyata za pobratimyavane na Sofia i Shanghai” (Borissov supports the idea of sister city partnership between Sofia and Shanghai), 23 November, Available at: https://www.mediapool.bg/borisov-podkrepya-ideyata-za-pobratimyavane-na-sofiya-i-shanhai-news242151.html (Accessed on 17 June 2023).

Mediapool (2019) “Radev predlozhi na Pekin direktni poleti, klon na kitaiska banka u nas i obsht nauchen centur” (“Radev offered to Beijing direct flights, branch of a Chinese bank in our country and a joint research center”), 1 July. Available from: https://www.mediapool.bg/radev-predlozhi-na-pekin-direktni-poleti-klon-na-kitaiska-banka-u-nas-i-obsht-nauchen-tsentar-news295120.html (Accessed on 13 June 2023).

Milanov, S. (2022) “Otnosheniyata mezhdu Kitai I Bulgaria: Istoriya, nashtoyashte I perspektivi” (“Relations between China and Bulgaria: History, Current State and Perspectives”), Podgled Info, 4 November. Available from: https://pogled.info/avtorski/Simeon-Milanov/otnosheniyata-mezhdu-kitai-i-balgariya-istoriya-nastoyashte-i-perspektivi.148375 (Accessed on 25 May 2023).

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Bulgaria (2021) “V Jiangsu New Yangzi Shipbuilding Co. be vdignat flagut na purviya ot seriyata 32 150-tonni korabi za nasipni tovari na Parahodstvo BMF AD” (The Flag of the First Ship from the Series of 32 150-ton Bulk Cargo Ships of Parahodstvo Bulgarian Maritime Fleet AD was Raised in Jiangsu New Yangzi Shipbuilding Co.), 24 August. Available from: https://www.mfa.bg/embassies/chinagc/news/30891 (Accessed on 23 July 2023).

Mission of the People’s Republic of China to the European Union (2023) “Key Documents on China-EU Relations”. Available from: http://eu.china-mission.gov.cn/eng/zywj/zywd/#:~:text=Since%20the%20inception%20of%20the,wide%2Dranging%20exchanges%20and%20cooperation. (Accessed on 10 July 2023)

Novini 247 (2022) “Edva pod 1% ot prekite chujdestranni investicii v Bulgaria idvat…” (“Only less than 1% of FDI in Bulgaria comes from…”), 11 November. Available from: https://novini247.com/novini/edva-pod-1-ot-prekite-chujdestranni-investitsii-v-balgariya-idvat_4962921.html (Accessed on 3 July 2023).

Nitsch, V. (2007) “State Visits and International Trade”, The World Economy, 30 (12), pp. 1797–1816.

NSI – National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria (2023) “Statisticheski danni” (“Statistical Data”). Available from: https://www.nsi.bg/bg/content/7496/статистически-данни (Accessed on 4 May 2023).

Novini 247 (2022) “Edva pod 1% ot prekite chujdestranni investicii v Bulgaria idvat…” (“Only under 1% of Direct FDI to Bulgaria comes from…”), 9 November. Avalable from: https://novini247.com/novini/edva-pod-1-ot-prekite-chujdestranni-investitsii-v-balgariya-idvat_4962921.html (Accessed on 16 June 2023).

Orbetsov, A. (2021) “Bulgaro-kitaiskite otnosheniya: sustoyanie i perspektivi” (“Bulgaria-China Relations: Present Condition and Perspectives”), Diplomatsiya, politika, ikonomika i pravo (Diplomacy, Politics, Economics and Law), 1, pp. 105-120.

Oxford Economics (2020) The Economic Impact of Huawei in Bulgaria, November 2020. Available from: https://resources.oxfordeconomics.com/hubfs/Huawei_Bulgaria_2020_V1.pdf (Accessed on 18 August 2023).

Pannier, A. (2020) “Bilateral Relations” in Balzacq, T., Charllion, F. and Ramel, F. (eds.), Global Diplomacy: An Introduction to Theory and Practice, Switzerland: Springer, pp. 19-33.

Popop, B. (2019) “Mozhe li Bulgaria da iznasya tutun za Kitai?” (“Can Bulgaria Export Tobacco to China?”), Investor BG, 23 September. Available from: https://www.investor.bg/a/461-bloomberg-tv/289880-mozhe-li-balgariya-da-iznasya-tyutyun-za-kitay (Accessed on 14 August 2023).

Presidency of Bulgaria (2023) “Ukaz №42” (“Decree No. 42”), 3 March. Available from: https://dv.parliament.bg/DVWeb/showMaterialDV.jsp;jsessionid=EAF52B222AD2EA7D09AC90CC589F994E?idMat=187600 (Accessed on 4 June 2023).

Shopov, V. (2022) “Let a Thousand Contacts Bloom: How China Competes for Influence in Bulgaria”, European Council on Foreign Relations, 10 March. Available from: https://ecfr.eu/publication/let-a-thousand-contacts-bloom-how-china-competes-for-influence-in-bulgaria/ (Accessed on 15 May 2023).