By Amalia Dania Berinde

Dania Berinde majored in English Literature in 2013 and later became an English-Romanian translator. In 2022 she began economic studies, enrolling in bachelor’s studies at the Vasile Goldis Western University of Arad, specialising in Accounting and Management Informatics under the mentorship of Professor Olimpia Neagu.

Blue Europe is an indipendent think tank and does not approve nor share the content or the position of invited authors. The article was created during the 2022 Blue Europe student contest.

Abstract

The NEET rate represents a category of young people aged between 15 – 29 years that are not in employment, education or training, this indicator is a relatively new one and more complex compared to the unemployment rate because it offers a wider view of the labour market correlating it with the participation in the educational system. This indicator sits high on the EU27 agenda due to its economic and social consequences, since the modern path from school to work has greatly been altered.

Evaluating the NEET rate is even more relevant in the pandemic context because each sector has been forced to adapt, bringing a change into the way a person works and studies, combining a new set of skills orientated towards digitalization, so many young people need to also adapt in order to avoid the scarring effects of a prolonged absence on the labour market. The need of reintegration into the labour market of these young people is of a great importance to governing bodies because of the costs it generates with social assistance systems and other expenditures.

The paper presents an analysis of the NEETs rate in Romania within the European context and using data presented by Eurostat, it highlights the main differences between the economic and social development before and after the pandemic, showing its progress along the years and presenting current and future plans in order to better help and support this category of young people.

Key words: youth, NEETs, labour market, European policies

I. Introduction

The economic strains across the European countries have been felt since the Great Recession in 2008, leaving some social groups more vulnerable than others and just as the world began to recover, a health crisis hit at the end of 2019, bringing entire industries to a halt. As economic sectors have recovered at various speeds and people adapted to a digitalised new world, a slight difficulty still remains to be tackled when it comes to one particular social group represented by the NEETs, meaning young people, not in employment, education or training. In the past, the analysis of labour market was based on two main indicators, the unemployment rate and the employment rate that were not able to fully satisfy the broad variety of transitions on this field, dividing the entire population into people who are already working and people who are in search of a job, leaving out the students or other categories of people who cannot work, such as the young people with disadvantages brought upon by a low level of educational attainment, the people with disabilities or health issues, those with an immigration background and even those who have willingly chosen to exit the labour market.

This paper intents to offer an analysis on the NEETs population in Romania compared to other countries in Europe by highlighting the main characteristics of this group, the risks they are exposed to by the long absence in the work field and the socioeconomic problems that need to be addressed. Particular attention will be paid to the effects the pandemic brought upon the vulnerable group of young people in Europe and Romania alike and how it affected their job prospects, taking into consideration the degree of digitalisation required in modern times. Finally, the paper details the programmes and actions taken by governing bodies in order to reduce the NEETs rate and avoid the future consequences of such disengagement from the labour market.

II. Defining the concept of NEETs

The concept of NEETs, meaning people not in employment, education or training, was introduced as an indicator to describe a broad array of vulnerabilities among young people with the age between 15-29 years, tackling issues such as unemployment, early school drop-out and even gender inequalities. The reason why this indicator is of a great concern for the European Commission has to do with the fact that the youth labour market is significantly more volatile than that of the mature workers and younger people are more sensitive to changes when in economic crises, when the unemployment rate rises, the youth compared to more experienced workers, “are often the first to exist and the last to enter the labour market” showing that they usually have to compete with more experienced workers in a market that has fewer jobs to offer to the population (Eurofound Report, 2015).

So, in order to offer a reliable cross-country comparison, the European Commission’s Employment Committee and the Social Affairs Council agreed in 2010 over a standardised indicator which could measure the unemployment rate among the young people who were not in education or training in order to foresee possible threats in this age group and take measures accordingly. According to the Eurofound report, Exploring the diversity of Neets, this indicator is calculated by dividing the number of young people aged between 15-29 who were not in education or training to the total population of young people of the same age, showing only the ones who are outside the labour market and the education system. (Eurofound Report, 2016)

For a better definition, when it comes to NEETs, international bodies such as the International Labour Organization offered clear guidelines to separate the unemployment rate, which includes young people who are unemployed, but in training, so they were economically active, from a more specific rate, the NEETs, which encompasses the inactive youth population not in training. According to them, his indicator only refers to people who meet two conditions simultaneously: they are unemployed and have not received any form of training or education (formal or informal) in the four weeks prior to the survey. (ILO 2015). Moreover, the same International Labour Organization offers a set of guidelines, defining the concept of unemployment as “active job search by persons not in employment who are available to [work]” and the potential labour force as referring to “persons not in employment who express interest [in working] but for whom existing conditions limit their active job search or availability” (ILO, 2018). In order to offer an even more accurate definition and proper categorization, the same organization offers us three criteria for guidance, they extent the area of unemployed to people who are not working, are actively in search of a job (in the last 4 weeks) and time availability, referring to whether a person is ready for work or not.

Moreover, when explaining the consistency of NEETs, there are seven subcategories that are to be taken into consideration to better understand and help the vulnerable youth. The short-term unemployed has the highest percentage, 29,8% of the NEETS, consisting of young people that have not been in the work-field within the last year and the long-term unemployed ranking second with 22% consisting of people that have been without a job for more than a year. Within the subcategories we can also find those who are not able to work because of family responsibilities (15.4% and mostly women and other adults with different incapacities), the non-vulnerable (12.5%), meaning young people taking a break from work or the artists, the re-entrants (7.8% who will soon leave the NEETs group), those with illnesses and disabilities (6.8%) and the discouraged (5.8% who have stopped looking for a job because they believe there are no opportunities for them) (Eurofound report 2016). Nevertheless, a prolonged absence from the work field is considered to be of a higher risk, leading to disengagement and even social exclusion, leaving them exposed to financial difficulties and poor mental health, even depression. The reasons for this phenomenon vary greatly for both sides, the employer and employee alike. The first side accusing the lack of skills acquired by young adults, even after pursuing a form of education, poor communication or problem-solving skills and even teamwork abilities. The latter side accuses a mixture of factors that hinders their employment prospects, such as living in a household with a low income and thus not being able to invest in education, single-parent household, living in the rural area where prospects are scarce and even disabilities. The Eurofound Report, Mapping Youth Transitions in Europe (2014) explains the relationship between the sides, which is greatly altered in the Southern Europe, blaming an economic imbalance, dual labour markets and an educational and training system that does not offer enough practical experience and involvement on behalf of the employer. The difference between NEETs rate across the Northern and the Southern part of Europe is also attributed to the educational model. The smoothest and fastest transition from school-to-work can be seen in countries such as Germany or Austria and the Northern ones, which adopt apprenticeship programmes where young people are able to combine school with early labour market experiences or learn first hand a trade, such as the case with vocational schools.

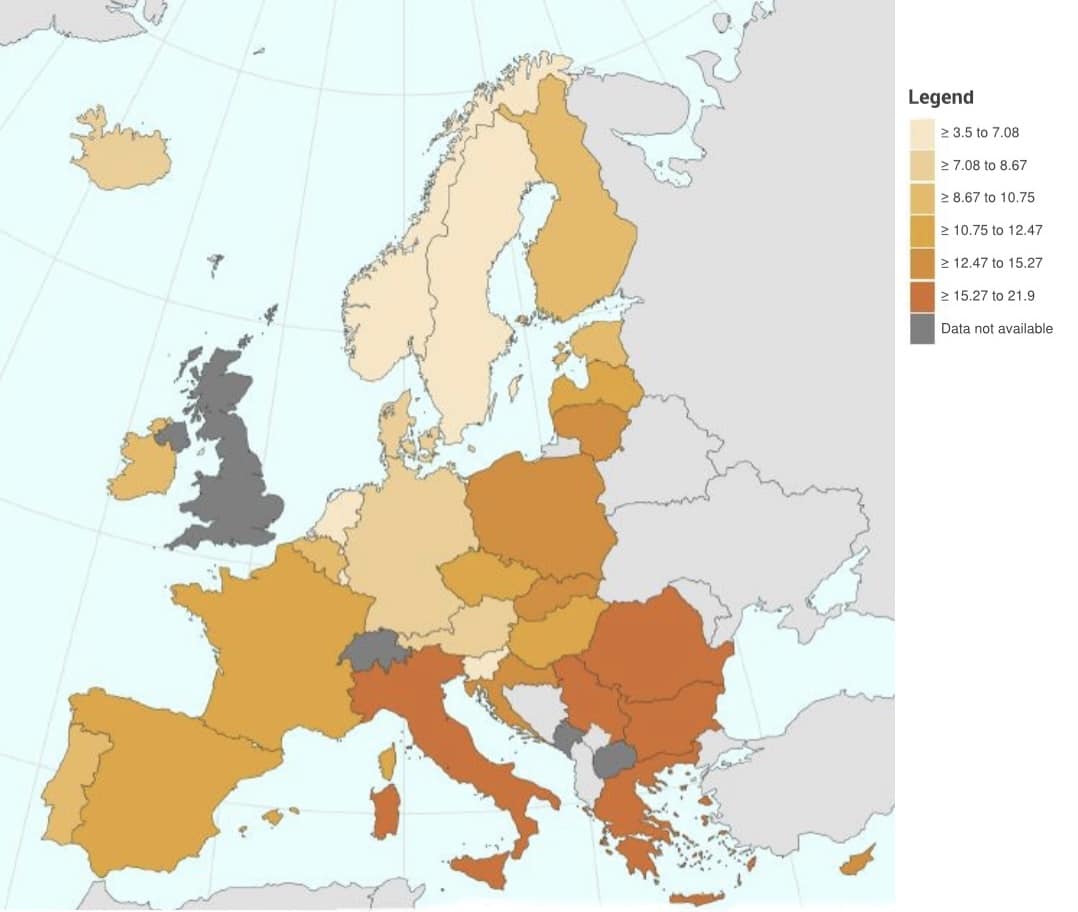

On the opposite side, the theoretical model adopted by Eastern Europeans, including Romania, and the Mediterranean one pose a challenge in the path of a young person to adulthood and financial independence. So, the level of educational attainment does influence the unemployment rate across the young people, but a greater influence has to do with the quality of education and training received. Therefore, young people with little, poor or no qualifications find it hard to successfully enter the work field and can sometime find themselves stuck in low paid jobs with little future prospects, especially in times of financial and economic crises. So, for the socioeconomic context, the NEETs pose a major problem since economic inactivity once a teen reaches adulthood can lead to various levels of employment scarring, this being the reason why their integration into the labour market or educational system sits high on the EU states agenda. According to Eurostat, last year it was found that NEETs with a high percentage of 10.9% for the EU27, the highest percentage being in Romania (19,8%), second came Italy (18,0%) and Greece (15,2%) third, while on the opposite side we have Sweden and Netherlands which rank the lowest with only 4.9% and 4.0%.

III. Economic and social costs

Figure 1: Young people neither in employment nor in education and training (NEET), by citizenship

Source: Eurostat code EDAT_LFSE_23

Source: Eurostat code EDAT_LFSE_23

Many studies show that there is a real link between education, unemployment and the economy of a country. One with a high rate of unemployment will have to face, among other problems, a lost output, meaning that the people who can not find work are not able to contribute to the country’s economy, leading to a loss of potential output with reduced investments (Jahan and Mahmud, 2013). This leads to a decreased consumer spending, since people have less income to spend, resulting in a reduction in aggregate demand which will force many firms to postpone investments and overall rises the risk of a recession. All these lead to a reduction in tax revenue and increased government spending, because a high unemployment rate reduces the direct and indirect tax revenue as people are not paying into the system, but increase the spending on social welfare programmes, thus further burdening the system.

The link between the three, education, unemployment and economy also goes backwards, the state of a country’s economy being able to influence the unemployment rate. The economy expert Will Kenton explains the term labour market “hysteresis” (Kenton, 2021) when addressing the unemployment matter and its multiple forms. He explains that hysteresis is a part of the cost of a recession and it presents long lasting effects on the economy and labour force alike, saying that after layoffs (possibly occurring due to recession, natural unemployment, technological advances or structural unemployment), when the economy bounces back and firms seek to re-hire, the unemployment rate still remains high. Among the reason for this phenomenon is the fact that people adjust to a lower standard of living and they may not be so motivated to returned to their previous state, moreover, firms can be reluctant to hire and may prefer to demand more of their remaining workforce or invest in technology.

Researchers use two terms when referring to the costs of the NEETs, young people not in employment, education or training. General concerns are high among the EU27 regarding the actual costs of the young people when not being employed or in education, thus affecting their short term and long-term work prospects. They have identified two cost frameworks, the first one relates to ‘public finances’ and encompasses welfare schemes and social assistance systems, such as unemployment benefits, child-care allowances, health and criminal justice expenditure. The second one, ‘total resource costs’ refers to estimates of the loss brought to the economy by this lack of engagement on the labour market, all derived from the social expenditures arising from the NEETs, in addition to the resources or opportunity costs to the rest of the society, such as the income of independent activities, own consumption production and private pensions. Both show the serious consequences a society has to face when the NEETs rate is high and the need to take action in order to facilitate and ease the transition from school to work. (Eurofound Report, 2015, Young people and Neets in Europe)

Bălan explains that for the European Union, the total costs derived from the failure of integrating the NEETs group was in 2011 at 153 bill euro, meaning 1.21% from the EU GDP, only to rise the following year to 162 bill euro, corresponding to 1.26% from the aggregated GDP, with countries such as Italy spending 34.9 bill Euro or France 21.3 bill Euro. Romania spent 2.135 bill. Euro in 2012, representing 1.67% from the GDP, while in countries such as Germany, Denmark or Sweden, the cost generated by NEETs, as share of GDP, was below 0.6%. (Balan, 2016).

IV. Analysing the NEETs based on statistical data

1. Participation in education and training

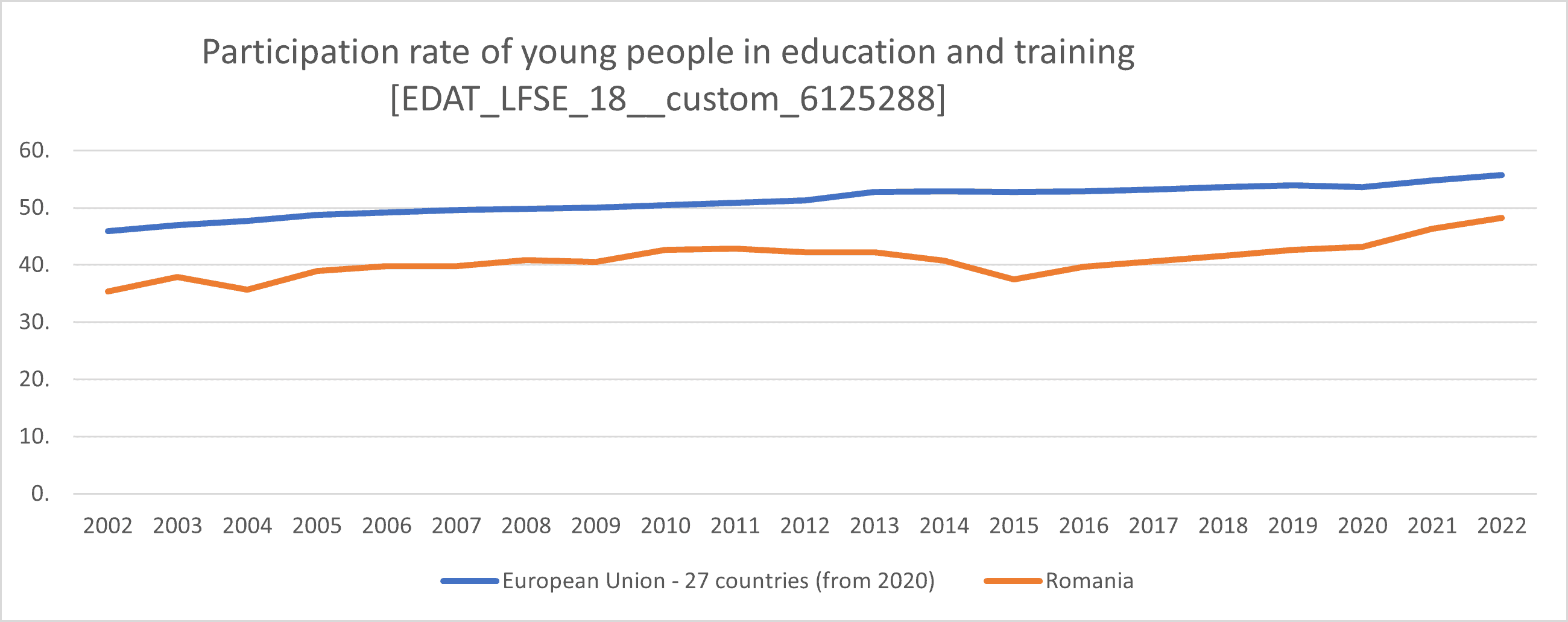

According to Eurostat, between the years 2002 and 2022, the participation rate of young people in education and training (incl. NEETs) registered a steady growth, reaching a high point in 2022, at 55,7% and a drop caused by the Pandemic in 2020 at 53.6% compared to the previous year (2019) with 0.3pp. In 2021 the percentage rose to 54.7%, meaning a total rise of 1.2pp compared to the previous pandemic year. In Romania, the trend is different, starting with the year 2016 the participation rate of young people in education and training started to increase gradually, reaching in the year 2022 at 48.2%. Before 2016, the rate fluctuates showing a degree of uncertainty when it comes to young people and the education system. Since 2002 and up to the last year, Romania showed an increase in the participation rate of 12.8pp showing a modern tendency of more and more young people pursuing an education.

Figure 2

Source: Author’s own computation based on Eurostat data EDAT_LFSE_18_custom_6125288

Source: Author’s own computation based on Eurostat data EDAT_LFSE_18_custom_6125288

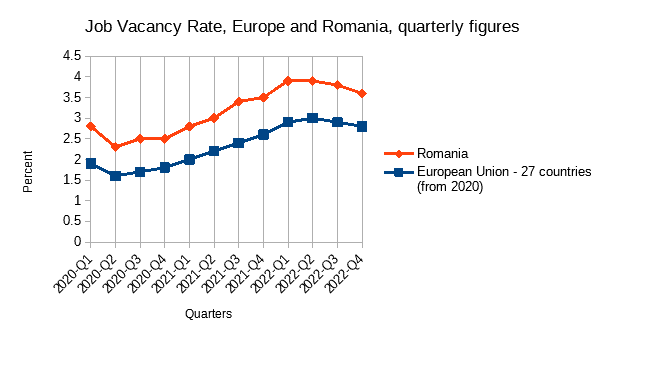

2. The Job Vacancy Rate

When analysing the employment rate and the population rise, a key factor needs to be considered, the rate at which new jobs were created or made available. The Job Vacancy Rate (JVR), measured the proportion of all vacant post or soon to be vacant and it helps offer a more accurate view on how easily can one enter the labour field. These figures can be used in order to predict unemployment in economic cycles, because during recession, the vacancy rate decreases as firms try to reduce cost with their work force which leads to higher unemployment rates. When looking at the figures offered by Eurostat, right after the pandemic hit the European countries, this rate began to decline to 1.6% in the EU27 and Romania alike, to 0.7%. The following years, as the population started to adapt to a new kind of work, remote or even hybrid, more jobs were made available. When in Europe, JVC rose with an uptrend, thus implying more jobs or even more opportunities, in Romania, the line remains roughly linear, with a slight increase of 0.2% for the second half of 2021, only to drop at the end of 2022 to 0.8%, meaning that the labour market offers little in terms of job opportunities for the Romanian population.

Figure 3

Source: Author’s own computation based on Eurostat data JVS_Q_NACE

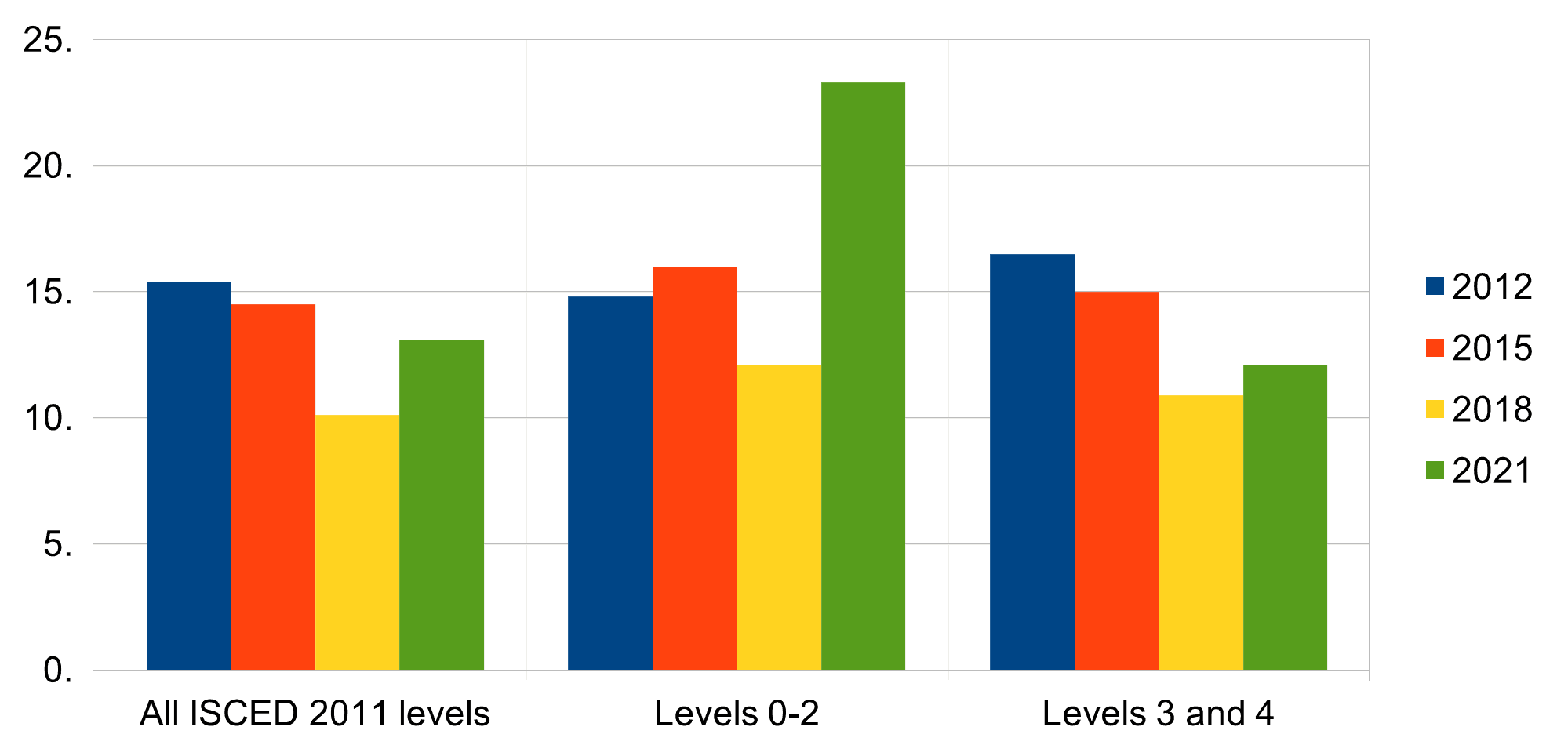

3. Unemployment rate by educational attainment

The level of education represents a major factor of young people when preparing to enter the labour force and especially for the future professional life, with possibilities of securing a job with decent remuneration and further career prospects. The link between the education acquired and the unemployment level can be seen in the Figure below, where lower education levels lead to higher unemployment figures. The people who have acquired a degree only up to lower secondary education found themselves the hardest to enter the labour market in 2015, 2018 and 2021, meaning that those without training or further education lost their job first after the pandemic hit compared to the people who have received a tertiary education. One reason for this could be the fact that people without tertiary education or training usually occupy low level positions due to their lack of skills or specific acquisitions, these jobs could easily be eliminated or the people could be replaced by new technologies. These entry levels jobs require little or no experience (they may offer on-the-job training) and no related education in order to qualify, although, for some companies it is not uncommon to ask for 1 to 3 years of experience. Typically, these positions are considered to be the lowest ranked compared to mid-level or senior level and thus are paid accordingly, although they can offer the employees the possibility of skills and experience development.

Figure 4: Youth unemployment rate, by educational attainment level

Source: Author’s own computation based on Eurostat data (YTH_EMPL_090)

Source: Author’s own computation based on Eurostat data (YTH_EMPL_090)

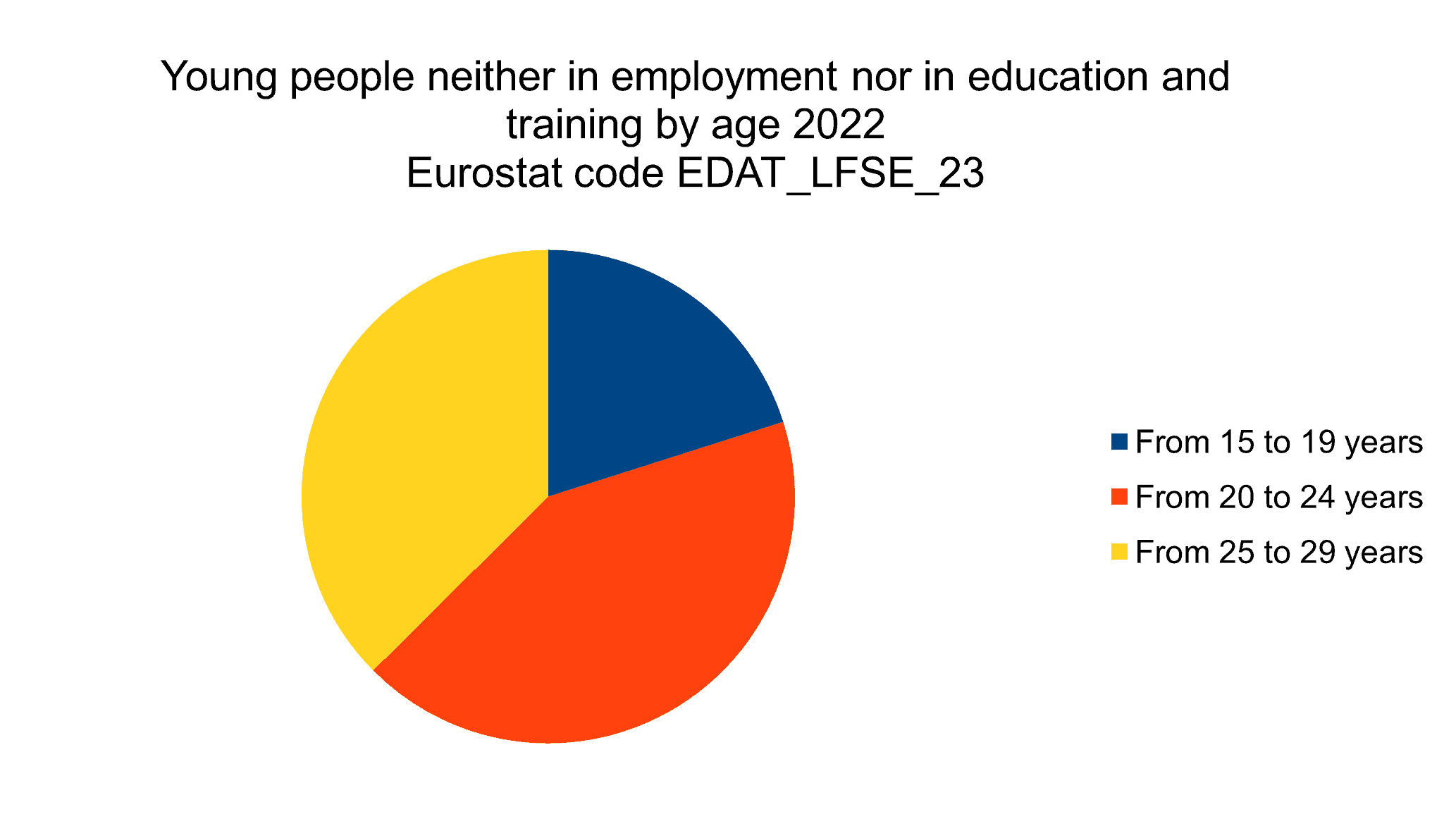

4. NEETs and age division

Dividing the NEETs rate into three main age groups shows how the unemployment rate increases once with age, concluding that a prolonged absence in the labour market does generate a scaring effect and diminishes the employment prospects of young people. In 2021, the rate in EU27 for the group aged 15-19 years who were not employed, in education or training was at 8.4%, for the next group, aged 20-24 years the rate was higher with 9.9 pp at 18.3% and the highest rate was registered with the last age group of 24-29 years, where the rate was at 18.6%, a rise of only 0.3pp. The same trend can be observed for the previous years, except only the year 2022 when the first age group registered a percentage of 8.05%, with a rise of 8.9pp for the following age group at 16.9% and the last group showed a decrease of 2pp at 14.9%, showing the degree of implication when it comes to the reintegration of the NEETs into the labour market.

Figure 5

Source: Eurostat, code EDAT_LFSE_23

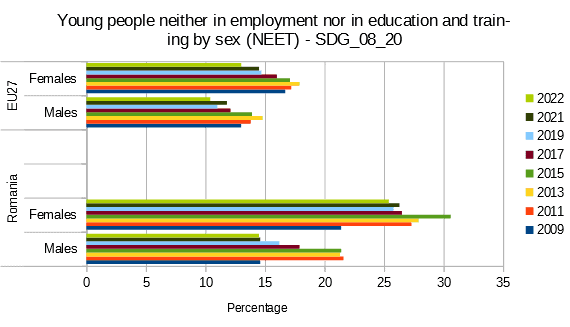

5. NEETs by sex

Another major component when analysing this indicator is represented by the degree of employment among women and men. The statistics offered by Eurostat show that there still is a gap between genders when it comes to the labour market degree of occupation, the NEETs rate for women being in 2022 in EU27 with 2.6 percent higher than for men, a difference that can be seen throughout the previous years also. The gap is even higher in Romania, for the same year, the difference was of 10.9% remaining more or less at the same level, except for the years prior to 2014 when the difference was at around 6%, the lowest being in 2011 at 5.7%.

Figure 6

Source: Author’s own computation based on Eurostat data (SDG_08_20)

Source: Author’s own computation based on Eurostat data (SDG_08_20)

National Institute of Statistics of Romania (NIS) provides the following figures for the total employment in Romania divided by main economic activities, showing us where the majority of people work and how these numbers fluctuated starting with the year 2019 up to 2021 within Tempo online data series. The data shows that the sector with the highest number of employees was the Manufacturing one with 1.192.979 people, but the sector that registered the highest growth after the pandemic (2020-2021) was the Information and Communication one, with a rise of 5.51%, showing just how much the pandemic changed the way people worked and studied. The next sector with the highest growth was Health and Social Work, with a rise of 4.18% in 2021 compared to the previous year. But the sector that registered a fall was the Extractive one, with 4.16% for the same reference years. In Europe, for the same years after Covid 19, Eurostat data shows, just like in the case of Romania, the sector with the highest increase in the number of employed people is Information and Communication,5.13%, but second came Real Estate Activities, 4.04% and third Professional, Scientific and Technical Activities, 3.10%, while a decrease was only registered in Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing of 1.64% (in Romania, the same sector registered a decrease of only 0.54%).

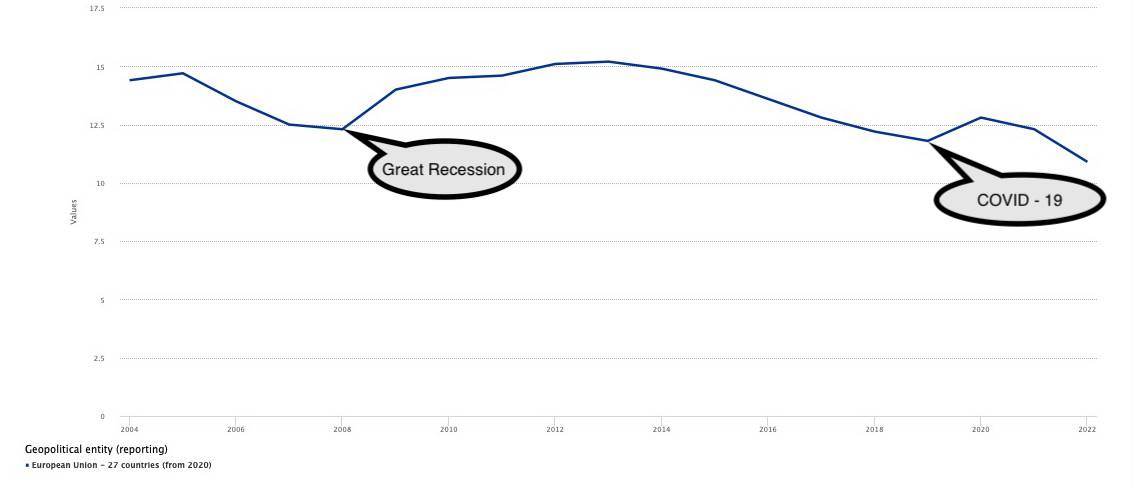

V. The impact of Covid 19 on the young generation

12 years after the Great Recession, the population faced another economic threat, one that not only brought a rise in unemployment rate, but also shook the medical system, the aftermath being felt still in the present days. On 11 March 2020, WHO, World Health Organization declared the Covid 19 outbreak a pandemic and soon enough Europe started implementing restrictive measures in order to protect the population. Among the first restrictions to affect the economy of Europe was the interdiction to travel, this sector being seriously affected and later on whole sectors began to shut down.

Many researchers talked about the social impact of Covid 19 that came with the lockdown, but this crisis severely altered the labour markets, forcing people to adapt to a new and digitalised way of working. When comparing the third quarter of 2019 with the third quarter of 2020, many countries across the EU showed a drop in their youth employment rate, the largest drop being registered in countries such as Lithuania, Portugal, Ireland and Spain, exceeding even 5pp while countries such as Hungary, Finland, France, Austria and Romania showed a smaller drop of around 2pp, showing just how much countries tried to reduce the effects of the lockdown over the population by implementing wage support schemes (Eurostat, 2022).

As previously stated, the younger generation is the more volatile when it comes to the fluctuations of the labour market, they are usually the last to enter the job market and the first to leave and all on top of a health crisis and its massive economic consequences that they need to bear. According to ILO 2021 this crisis was particularly severe for the youth population, affecting it in three main points, firstly, it disrupted the young generation from their studies and a pause in education or training brings long term effects, secondly, it made it more difficult for young jobseekers and new labour entrants to secure a job and lastly, the pandemic brought not only job losses, but also income cuts, along with deteriorating employment quality.

Eurostat shows that in 2020, due to the Covid 19 impact, the unemployment rate rose by 1.4pp compared to the previous year for the NEETs category and showed a slight improvement in 2021, registering a fall in the unemployment of 0.3pp (Figure 9). Another important analysis shows the proportion of young people working in different sectors, showing the degree they were affected by the pandemic. According to Eurofound Report, Impact of Covid-19 on young people in the EU, 2021, the sector with the largest proportion of employed young people was in accommodation and food services, 13% and since this sector was the worst affected, travel, tourism, dining were reduced and even closed which probably led to job losses. The next sectors with a high percent of youth employment were wholesale and retail and health and social work, both at 11%, and they also registered changes in activity, but less likely to generate job loss among the young generation. The next sector where young people were affected was arts, entertainment and recreation (10%) and here also, they suffered from restrictions as social distancing measures were imposed. As stated previously, the young people are more vulnerable to economic changes and when taking into consideration the restriction imposed and the sectors affected by the Covid-19 pandemic which have the highest rate of youth employed, it is clear that they had been facing the highest risks of job loss that led to independence loss, forcing them to rely on the financial support of families.

Figure 7

Source: Eurostat – Young people neither in employment nor in education and training (NEET), Europe, code EDAT_LFSE_23

VI. Steps towards a better future of NEETs

For over three decades the European Union has been actively involved in the process of offering guidance and learning opportunities for these vulnerable social categories by developing various programmes and implementing policies for other countries within Europe to adopt. These measures have as sole purpose the rise in participation rate of young people in education and employment alike. For this reason the term “learning mobility in the field of youth” appeared that helped young people through exchange programmes move across countries, in and outside Europe, in formal and non-formal learning settings, promoting intercultural learning and integration. (Briga, 2018) The first initiative of the European Union in the youth sector developed at the end of the 1980s through youth exchange programmes such as Erasmus in 1887 and Youth for Europe 1988, as stipulated in The European Union Treaty, signed at Maastricht in 1992, Article 126 § 2 which states that Community actions should be aimed at “encouraging the development of youth exchanges and of exchanges of socio-educational instructors;” (The Treaty on European Union is signed in Maastricht on 7 February 1992 and enters into force on 1 November 1993 )

Another example of such measures taken represents the European Youth Foundation (EYF) which was established in 1972 by the Council of Europe in order to offer educational and financial aid to the young generation through specific and targeted activities. This foundation has an annual budget of 3.8 mill Euro (composed of each Council of Europe member state’s contribution, to which can be added voluntary contributions from individual states). In 2021, a total grant of 3 616 200 Euro was distributed to 134 youth organizations that helped support national and local activities which ultimately reached youth workers and leaders by improving their work, good practices and mitigate the effects of Covid19 pandemic. Since last year, according to the European Youth Foundation Report, the number of organizations dedicated to youth development registered with EYF rose by 7%, both from local and national NGOs. (European Youth Foundation, 2021).

Later in 2007 began Youth in Action, another programme oriented towards building identities and sharing culture among the youth. To combat the negative effects the pandemic left, a bigger budget has been approved in order to invest more in the young generation, amounting to €1 835,3 billion, together with the recovery package “Next Generation EU” (2021-2023). One of the pillars ‘’Make it strong” aims to encourage young people into taking up science and technology, guiding the new generations towards the digitalised jobs of the future and even offering grants and loans to young entrepreneurs, because sometimes, the problem of unemployment lies not with the young people trying to enter the labour market, but with the quality and conditions of the jobs made available for them. The unemployment problem cannot be solved solely by entering tertiary education, but by creating jobs since new technologies and a highly digitalised world are both developing and destroying the definition of a job. So, the current policies should be aimed at offering people the set of skills required for them to secure a stable income and prospects for progress (ILO, 2016).

The Youth Guarantee fund was conceived in 2013 as a response to the rise of the NEETs rate, in order to help young people get back into education, training or employment. According to the Eurofound Report, Exploring the diversity of NEETs, the Youth Guarantee Fund revolves around three main dimensions. The first one is early activation, meaning that young people are helped to avoid inactivity within four months of becoming unemployed or leaving formal education, thus reducing the scarring effect of long term disengagement. The short and long term interventions represent the combination of long term reforms with immediate measures in order to meet the needs of the young people. The personalised and integrated support approach intends to smoothen the path to re-entering employment, education or training through quality job offers, apprenticeships, traineeships or further education. The allocated budget from the Youth Employment Initiative was 6.4 bill Euro for 2014-2022, adding national resources.

VII. Conclusion

The NEETs represent a diverse and heterogeneous group of people that cannot simply be captured by employment and unemployment rate. Moreover, this rate is of a great importance for governing bodies since they have such a great impact on a country’s economy, all NEETs not being able to accumulate human capital because of their absence in the labour market and educatioal system which can ultimately lead to employment scarring, future financial consequences and especially costs through social wellfare schemes. Statistics showed that the unemployment rate among the young and vulnerable is highly linked with the educational model, a cleare difference being felt between the Nordic one based on apprenticeships and trainships and the Eastern one based more on theoretical acquisitions which cannot offer the skills and practices needed to successfully enter the labour market. This along with other factors such as the emigration background, economical state of a country, degree of participation in education can lead to a high labour disengagement. The Covid 19 pandemic brought a rise in the NEET’s rate especially in sectors where young people were mostly employed, but once the restrictions began to easen, the population started to adapt to a new and digitalised way of working and studying and with the help of programmes funded by the European Union, aimed at reintegration, culture sharing and re-entrance into the labour field and educational system, it was possible to smoothen the transitions from school to work.

References

1. Balan Mariana, 2016, Economic and Social consequences triggered by the Neet youth

2. Briga Elisa, May 2018, Learning mobility in the field of youth, full article: https://pjp-eu.coe.int/en/web/youth-partnership/learning-mobility/-/asset_publisher/n6SpjB4sOp1q/content/european-conference-framework-quality-and-impact-of-young-europeans-learning-mobility-

3. Eurofound Report, 2014, Mapping Youth Transitions in Europe, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg

4. Eurofound Report 2016, Exploring the diversity of NEETs, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg

5. Eurofound Report, 2021, Impact of Covid-19 on young people in the EU, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg

6. European Youth Foundation, Annual report 2021

7. Eurostat, 2022 – COVID-19 strongly impacted young people’s employment, full article: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/ddn-20220331-1

8. International Labour Organization 2015, What does NEETs mean and why is the concept so easily misinterpreted?

9. International Labour Organization, 2018, Measuring Unemployment and the potential labour force in labour force surveys

10. International Labour Organization, 2021, An update on the youth labour market impact of the COVID-19 crisis

11. Will Kenton, 2021, Hysteresis: Definition in Economics, Types and Example, full article https://www.investopedia.com/terms/h/hysteresis.asp

14. Massimiliano Mascherini, 2015, Young people and NEETs in Europe: First findings, European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, full article: https://movendi.ngo/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/NEET-and-youth-unemployment.pdf

15. National Institute of Statistics of Romania (NIS), link: http://statistici.insse.ro:8077/tempo-online/#/pages/tables/insse-table

16. Sarwat Jahan and Ahmed Saber Mahmud, 2013, What is the Output Gap?, full article https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2013/09/basics.htm

17. The Treaty on European Union is signed in Maastricht on 7 February 1992 and enters into force on 1 November 1993 , Official Journal of the European Communities (OJEC). 29.07.1992, No C 191. [s.l.]. ISSN 0378-6986. “Treaty on European Union “, p. 1., link to treaty: https://www.cvce.eu/content/publication/2002/4/9/2c2f2b85-14bb-4488-9ded-13f3cd04de05/publishable_en.pdf