DIGITISATION IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPEAN COUNTRIES: CYBERSECURITY CONCERNS, CORPORATE RESPONSES, AND GOVERNMENT STRATEGIES By Manel Bernadó Arjona

- The Downside of Digitisation: Cybersecurity Implications

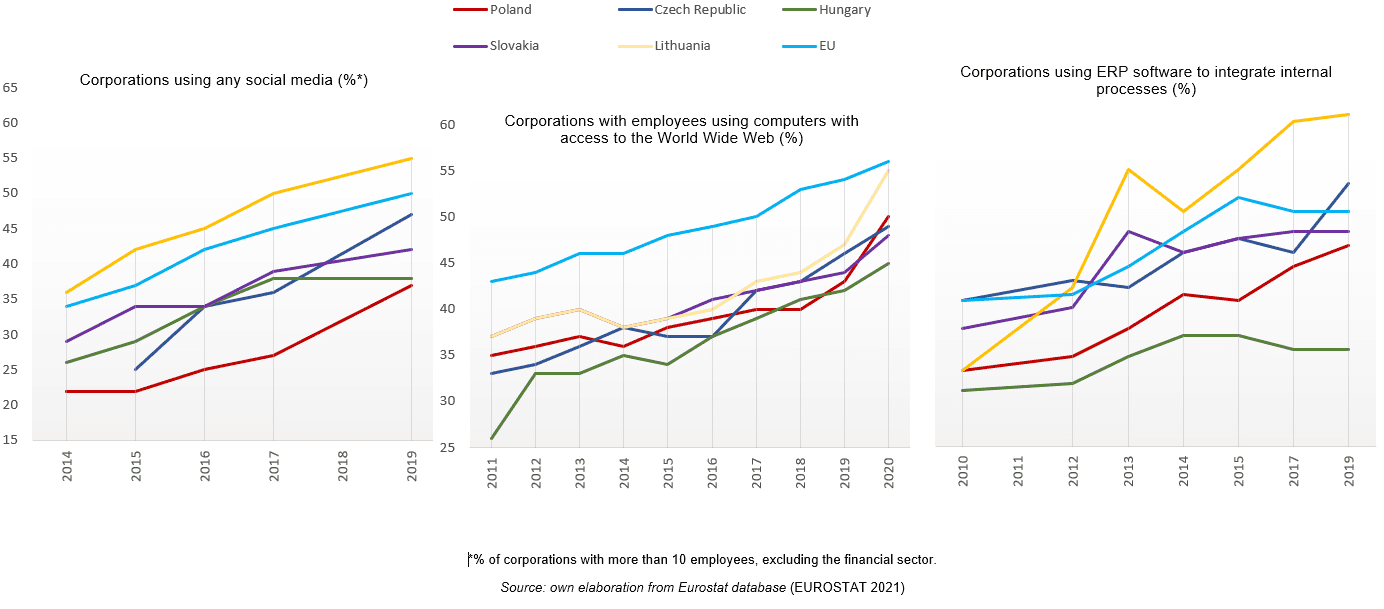

The rapid increase in the use of digital tools across all strata of society requires strong, well-oriented cybersecurity measures that tackle multifaceted cyber risks. The entry point of most cyberattacks originate in the World Wide Web and rely on social engineering, configuration errors, or brute force to gain entry to a system. For this reason, as people and companies use the internet more frequently and for more purposes, individual and corporate vulnerability increases (ENISA 2020a).

For companies, the use of IT solutions in the workplace and the business structure entails a certain dependence of the business model on these technologies. As employees use computers with access to the internet more frequently, the prospects of an insider attack against either company systems or company data arising from unsafe employee cyber practices increase exponentially. In this regard, in 2020 alone 71% of companies in the EU experienced malware activity that spread from one employee to another (ENISA 2020a). The integration of software within the business process makes the entire corporation vulnerable to malware, SQL injections, Denial of Service (DoS) attacks, and ransomware. The use of social media accounts gives room for phishing, password attacks and ransomware as means of coercion, or simply to hurt the public image of the company.

Cybersecurity concerns do not only put the economy of CEE countries at risk, but also their democratic foundations. When combined with other asymmetric methods such as disinformation campaigns or coercive economic pressure, cyberattacks can be used to discredit public institutions and cause societal divisions, with the goal of undermining governments (European Parliament Research Service 2019).

Individuals are also increasingly exposed to cyberthreats as they integrate technology into their lifestyles. The widespread use of social media and the quantity of personal data provided by them on the internet, especially in key sectors such as banking, education, or health –including the rise of e-government platforms to interact with public authorities and submit forms with personal data–, help in multiplying the potential security breaches in individuals’ digital presence. The lack of acknowledgement of the potential risks inherent to the use of IT products and services, and hence the lack of prevention against cyberattacks of any kind, makes individuals an increasingly attractive target for cybercriminals.

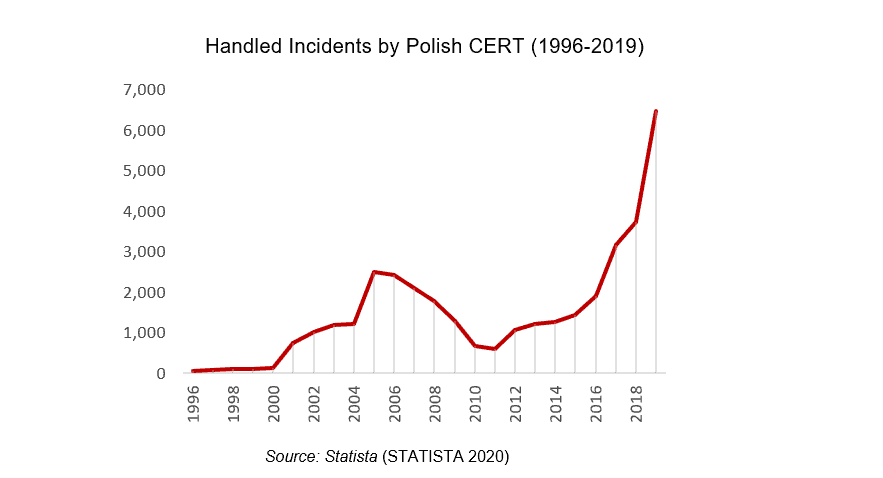

Data on cyberattacks in the CEE region for 2020 reflects this state of affairs. Polish historical data available for the past 30 years reflects how the amount of detected and handled cyberattacks has skyrocketed. According to CERT Polska, the first Polish computer emergency response team (CERT), after an initial frenzy in the 2000s, the amount of cyberattacks went back to a few hundreds in 2010, and has increased to over 6,400 since then. These figures only account for the cyberattacks that have been detected and managed by this CERT, and therefore disregard the vast majority of cyberattacks which either go undetected or, due to social engineering techniques, simply remain unreported.

Source: Statista (STATISTA 2020)

According to the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA), the most targeted sectors in 2020 were digital services, financial services, healthcare services, and government administrations, and the most common types of attack were ransomware, phishing, trojans, card skimming and business e-mail compromise (ENISA 2020a).At the corporate level, a significant amount of companies in the CEE countries suffered at least one information and communications technology (hereinafter, ICT) security incident –including unavailability of ICT services, destruction or corruption of data, or disclosure of confidential data–: 21% of all companies in the Czech Republic, 16% in Lithuania, 15% in Slovakia and Hungary, and 13% in Poland (EUROSTAT 2021).

In broad terms, in Lithuania, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia around 11–12% of all computers and 2–3% of all mobile phones were infected with malware in 2020, with the Czech Republic falling back to only 4.9% of all computers and 1.6% of all mobiles (STATISTA 2020).

Another area of concern is the steep increase in the use of cloud computing services in the past 5 years by both companies and individuals, a pattern that data from Eurostat reflects in all analysed CEE countries. By storing data in the cloud in any form, the amount and sensitivity of available information to be exposed through data breaches or any other cyberattack increases, and so does the attractiveness for prospective cybercriminals to target SMEs and individuals, which are less likely to have strong ICT security protocols and practices.

In the context of increasing use of the internet in computers and mobile phones both in companies and households, these figures indicate a massive amount of cybersecurity breaches and incidents beyond those reported, hence making cyberthreats one of the most disruptive elements for businesses and societies in CEE countries.

- Corporate ICT Security Responses

To counter these attacks, corporations in CEE countries have adopted several measures. In general terms, around 90% of all companies in the analysed CEE countries use some form of ICT security measure (EUROSTAT 2021). Nevertheless, there are relevant differences in the degree to which companies in different CEE countries implement specific ICT security measures when compared to the EU aggregate level.

| % of all companies (2019) using: | Poland | Czech Republic | Slovakia | Hungary | Lithuania | EU |

| Up-to-date software | 81% | 89% | 85% | 82% | 80% | 87% |

| Documents on ICT safety measures, practices and procedures | 23% | 32% | 28% | 17% | 36% | 33% |

| Data backup to a separate location | 57% | 82% | 72% | 59% | 68% | 76% |

| Periodic ICT risk assessments | 24% | 37% | 30% | 14% | 24% | 33% |

| Employees aware of their obligations in ICT security issues | 49% | 76% | 64% | 48% | 67% | 61% |

| ICT security compulsory training | 32% | 31% | 29% | 10% | 21% | 22% |

Source: own elaboration from Eurostat database (EUROSTAT 2021)

As it can be appreciated, Polish and Hungarian companies fall behind vis-à-vis the European benchmark in most fields, while Slovakian and Lithuanian corporations are on par with the EU aggregate. The Czech Republic consistently surpasses EU levels in most of the indicators. It is worth pointing out that despite the visible differences, companies in CEE countries do have mechanisms in place to prevent and deal with cyberattacks. Or at least they do on paper.

In 2018 the platform CYBERSEC HUB released a report called “Cyber Threat CEE Region 2018”, which contained a study conducted through polls on over 500 SMEs in Poland, Czechia, Romania, Hungary and Slovakia (The Kosciuszko Institute 2018). The report revealed that over 65% of companies in the region lacked a cybersecurity strategy to protect customer data, with Poland being the most promising country in this regard, and only 23% of Slovakian and Czech companies doing so. In addition, the study showed that only half of the companies that were asked actually made regular data back-ups, and almost 60% of them used classic, outdated anti-malware software as means of ICT security against cyberattacks.

It is then safe to affirm that despite the ICT security measures implemented by companies in CEE countries evolve similarly to those at an EU level, there are still important gaps to be filled to be on par with the rest of the EU. However, even across the EU, the majority of bottlenecks in the adoption of proper ICT security measures in the private sector comes from non-technical factors, such as a lack of awareness and funding devoted to cybersecurity (The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies 2018). It is imperative that, as companies grow and transition towards digitisation, they acknowledge their digital vulnerabilities and embrace the mechanisms necessary to prevent and control cyberattacks.

In addition, given the rising cyber risk due to increasing cyberthreats, and with an average cost per data breach of $4 million, companies should consider acquiring a cyber insurance that covered the company in the event of an attack, and which for now are only held by the largest companies in CEE countries (Legal Week Intelligence, CMS Law 2018).

-

Governmental responses and challenges

The primary motivation behind cyberattacks is financial (ENISA 2020a, p.13), and yet the consequences of these attacks transcend the financial sector. As technology is further embedded in our societies, cyberattacks acquire the potential to target the population, industrial network, and critical infrastructure of a country. As an example, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic the Brno Hospital in the Czech Republic suffered a cyberattack that shut down all network systems and forced to reroute patients, having critical effects as the hospital was one of the biggest COVID-19 laboratories in the country.

The fight against cyberthreats must therefore become a priority for public administrations as well, rather than remaining a private sector concern . Such is its relevance that most European governments, as well as regional and international organizations, have started dedicating increasing efforts to developing cybersecurity strategies. At a national level, some European countries embarked in this enterprise by drafting the first national cybersecurity strategy documents in the late 2000s. Since then, most countries have developed their own, and all of them have been updating them to the ever-changing cyberthreats. At a European level, the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) was created to monitor and assist EU countries in their cybersecurity endeavours, and more recently has assumed operational and legislative capacities that enhance regional cooperation in the field.

National Strategies

ENISA has been tasked with gathering and analysing the cybersecurity efforts of EU member states. To facilitate the analysis of national strategic cybersecurity documents, ENISA counts with an interactive map displaying those of each EU member state (ENISA 2021a). This article enumerates some of the features that characterise the national cybersecurity strategies of the CEE countries analysed.

In Poland, the National Framework of Cybersecurity Policy for 2017-2022 identified cyberthreats as a growing priority and established a vision for 2022 under which Poland would be more resilient to cyberattacks to secure the provision of public and private services by Polish operators in the cyberspace. The document identifies the main cybersecurity objectives and the steps towards their completion. Some of the objectives in this document –and in most documents of this nature– include the capacity to prevent, detect, minimise and counteract cyberthreats, increasing the national competence in cybersecurity, and building a strong international position in this field. Although the 2013 National Cyber Security Strategy of Hungary follows a similar approach by setting similar objectives, not only it is outdated, but it fails to establish a specific course of action to achieve them, vaguely enumerating the desired outcomes and listing what ought to be done to reach these.

Likewise, the National Cyber Security Strategy of the Czech Republic for the period from 2015 to 2020 enshrines similar objectives, stressing the importance of collaborating with regional and international organisations such as the EU and NATO and offering unitary responses to borderless cyber challenges, and pursuing the protection of the overall integrity of the cybernetwork used by its population, rather than protecting individual systems.

The Cyber Security Concept of the Slovak Republic emphasizes the relevance of government intervention in securing the cyberspace, as insufficient protection can result in vulnerabilities of the national interests, the country’s constitutional and public order, the overall social and economic stability of the state, and the protection of the environment – hence specifying and exemplifying the utmost importance of state participation in the matter.

Last but not least, the 2018 National Cyber Security Strategy of the Republic of Lithuania is one of the most complete documents of the CEE countries analysed. Not only dos it set clear targets and the means to attain them, both at a national and international level, and through private-public partnerships, but it establishes who bears responsibility for its implementation and which criteria shall be used to assess it. Thus, the document provides mechanisms of accountability to prevent the measures described in it from staying in mere theory.

Although the successful adoption of national cybersecurity strategies lays a strong foundation for the protection of private and public agents against cyberthreats, they remain insufficient to accomplish their goal for the most part. the work accomplished of governments in CEE countries so far reflects political will to fight against cybercrime, which will undoubtedly be very relevant in the near future as cybersecurity grows in importance.

Besides the inherent challenge of cybersecurity concerns evolving much faster than legislative developments and executive responses, there are also certain shared, common challenges specific to CEE countries which should be addressed at a regional and international level.

International Initiatives

In broad terms, the national cybersecurity strategies of CEE countries follow the blueprint of ENISA and NATO guidelines. These include establishing objectives in key areas, such as law enforcement, critical infrastructure protection, and international cooperation, as well as identifying a national incident management centres (CERTs) and the governmental body in responsible for coordinating the implementation of the national strategy.

As part of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, the countries analysed in this paper participate in the cybersecurity projects developed by the Alliance. NATO concerns itself with cyber defence as part of its collective defence system, and promotes cyber education, information sharing, and reciprocal assistance against cyber threats. Moreover, NATO members can count on the Cyber Rapid Reaction teams to provide them with assistance at any time in the event of a cyberattack. At the 2018 Brussels Summit, NATO members agreed on the creation of a Cyber Operations Centre which will possess both defensive and offensive capacities, and which is expected to be operational by 2023 (Reuters 2018).

NATO members have been a target of cyberattacks of Russian and diverse origin (EUISS 2018). However, it was not until Russia made an extensive use of digital hybrid warfare in the 2014 annexation of Crimea that the Alliance updated its cyber policy to include cyberattacks in the collective defence umbrella (Atlantic Council 2014). By considering serious cyberattacks as the digital equivalent of attacks under article 5 of the Washington Treaty, NATO’s collective defence umbrella also includes digital aggressions against Allies (NATO 2019).

The efforts of the Transatlantic Alliance are vital for countries in the CEE region to prevent, deter and repel cyberattacks. However, NATO’s capabilities are only military, and therefore do not constitute an integral supranational cybersecurity project. To evolve, the Alliance has increased its cooperation with the European Union, which does count with the legislative mechanisms to provide a shared, integrated response in all EU member states (Ilves, et al. 2016). Since its creation in 2005, ENISA has moved from simple training purposes to acquiring operational and regulatory capabilities in the field of cybersecurity.

Further efforts culminated with the creation of the EU Cybersecurity strategy in 2013 for “an open, safe and secure cyberspace”. The strategy establishes five priorities addressing civilian, criminal, military, industrial, and international objectives (European Commission 2013). To achieve them, the strategy includes the creation of a European Cybercrime Centre and the proposal of a network and information security (NIS) directive. The 2016 NIS Directive, to be transposed into EU members until 2018, focused on enhancing the individual national cybersecurity capabilities of EU member states, promoting cross-border collaboration, and ensuring their supervision of critical national market operators (ENISA 2021c).

Four years after its creation, a 2020 report by ENISA found that 82% of the organizations affected by the NIS Directive perceived a positive impact on their information security (ENISA 2020b). These organizations include French, German, Italian, Spanish, and Polish companies classified as either Operators of Essential Services (OES) or Digital Service Providers (DSP). OES are companies whose main activity relates to key sectors such as energy, transport, banking and financial services, health, and critical physical and digital infrastructure, and DSPs refer to online marketplaces, online search engines, and cloud computing services – thus, all of them working in critical fields for national stability.

The study found that over 80% of the surveyed organizations declared they had either already implemented or were in the process of implementing the NIS Directive. In numbers, the success of the NIS Directive translates in an average €175.000 budget per organization for its implementation, with more than 50% of the organizations having had to hire additional security experts to that effect. In fact, almost 60% of the organizations reported to have suffered major information security incidents, two thirds of these declaring to have resulted in a direct financial impact of up to €500,000 (ENISA 2020b), a concerning reality that underpins the importance of establishing EU-wide frameworks fostering cybersecurity planning among EU Countries.

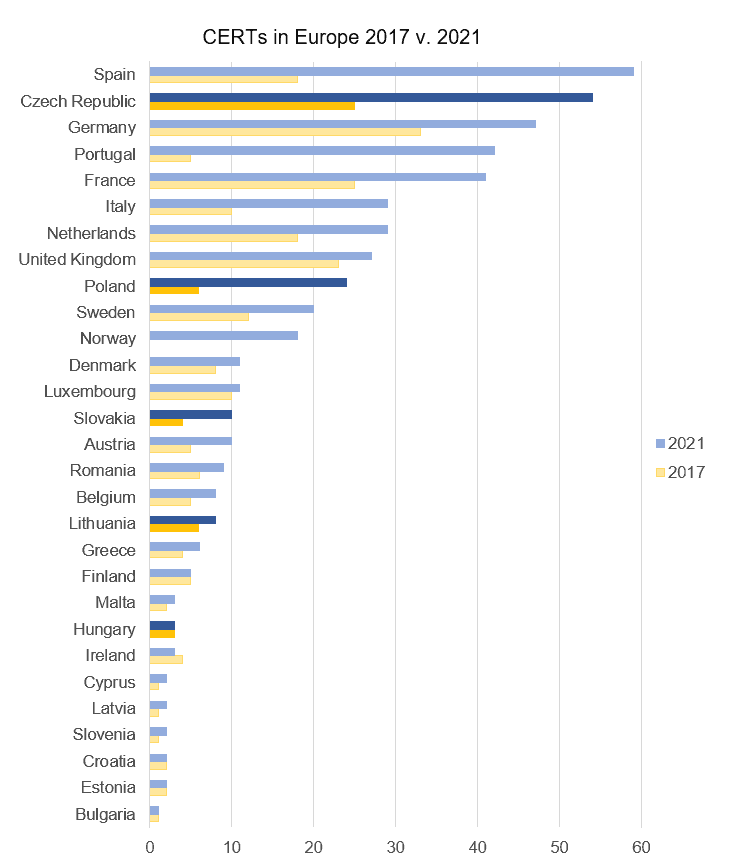

The effect of the NIS Directive can also be appreciated in the rising number of CERTs across Europe. In the year after its adoption in 2016, all European countries already complied with their obligations under the NIS directive to count with at least one CERT to coordinate the responses against cyber threats at a national level. Five years after its adoption, the amount of CERTs, both public and private, has increased significantly. However, there are still major differences in the degree of maturity of the response capabilities across European states. This disparity remains one of the most important obstacles to accomplish further cross-border cooperation against cyberattacks at a regional level (ENISA 2021c).

These differences are also present in the CEE region. The Czech Republic leads the CERTs ranking at an EU and CEE level with 54 centres, having almost doubled its response units from 2017 to 2021. It is followed by Poland, which has quadrupled its CERTs in four years, moving from 6 in 2017, to 24 in 2021. Slovakia, Lithuania, and Hungary fall behind significantly with only 10, 8, and 3 CERTs, respectively (ENISA 2021b, The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies 2018, 48-51). It is therefore clear that even if the 2020 ENISA report evidences a shift towards the strengthening of ICT security investment in key sectors as a result of the NIS Directive, data shows that the impact of the European Directive in enhancing response capacities has not been homogeneous across EU and CEE countries.

Source: own elaboration from ENISA database (ENISA 2021b) and HCSS (The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies 2018, 50).

Outside EU or NATO-level cooperation initiatives, in the past decade there have been several initiatives to strengthen cooperation among Central European countries. In 2013, the Czech Republic and Austria initiated the Central European Cyber Security Platform (CECSP), a regional framework that would include the four Visegrád countries (Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, and the Czech Republic) and Austria. The main goal of the CECSP is to achieve tighter regional cooperation that allows the CEE region to act as a whole in European and Transatlantic fora to represent a single regional position discussed beforehand. In this regard, cooperation among CEE countries under the CECSP has already been used to influence the debate and negotiation for the NIS Directive and the EU Cybersecurity Act. The CECSP also provides a regional platform for CEE countries to discuss and cooperate in the legal and technical implementation of EU and NATO initiatives (Tikos and Krasznay 2019).

Challenges

There is still much to be done for CEE countries to achieve well-developed, coherent pro-ICT regulatory frameworks, including those regarding IP/IT protection laws. This has rendered a sub-optimal development in ICT industries in the region, including the cybersecurity sector (Digital McKinsey 2018). To overcome these challenges and enhance their digital economic growth, CEE countries should avoid the unnecessary proliferation of inefficient ICT-oriented norms by creating a coherent legal framework that addressed the main concerns in the sector and fostered international and public/private synergies. Promoting digital economic growth in a regulated, controlled environment would also help reduce cybersecurity threats and facilitate the implementation of corporate and national cybersecurity strategies.

In addition, putting an end to the digital “brain drain” or talent leakage CEE countries suffer from would allow their ICT and cybersecurity industries to flourish and grow more independent from foreign ICT services and products providers (Digital McKinsey 2018). Strengthening national actors in the CEE cybersecurity market would increase the autonomy of CEE countries in cybersecurity debates in regional and international organizations. Moreover, by coordinating their actions in multilateral fora such as the EU or NATO through dialogue in regional institutions like the CECSP, the CEE region would be able increase its influence over key debates in the field of cybersecurity.

The differences in the implementation of common cybersecurity objectives under international organizations prevent a deeper level of cooperation between CEE countries. Further developing their response capacities by strengthening their national networks of CERTs is a necessary step foster reciprocal assistance synergies among EU and CEE countries.

Overall, despite the efforts made to cooperate in the field of cybersecurity have rendered promising results, EU and CEE countries still require from deep legal and policy changes to achieve their true potential – changes that will need from great political will to be implemented.

- Conclusion

Central and Eastern European countries are transitioning towards digitisation at the corporate, individual and public level. The evolution in the indicators studied here prove that computer and internet usage is more accessible and generalized in CEE countries. This transition entails strong cybersecurity concerns for the private sector. The more the degree of digitisation in CEE countries, the more attractive and vulnerable they will be to prospective cyberattacks. Investing in cybersecurity may sometimes not appear a critical priority given its defensive nature, for it is only needed when being targeted by a cyberattack. However, leaders in corporations and public entities should look beyond the absence of tangible, immediate benefits from adopting strong ICT security measures, and consider them as an investment to ensure their future stability and success.

Corporations in CEE countries have generally started developing and implementing ICT security measures, and although some of them are on par with or even outperform EU levels, they are still insufficient to effectively deter and repel cyberattacks. Governments in CEE countries have made efforts in developing national cybersecurity strategy documents, thus reflecting their compromise to participate in building strong national cybersecurity systems.

However, measures put in place to prevent, detect, and counter cyberattacks remain insufficient. Corporations generally lack a cybersecurity strategy that provides them with complete, coherent security measures. They are not updated frequently enough, and fail to be effectively implemented as to achieve the objectives they identify. Having a comprehensive, well-drafted, and up-to-date corporate cyber strategy is vital to have effective protection measures in the fast-changing cybersecurity environment. Counting with sufficient employee training, systems monitoring, threat detection, and breach reporting protocols and practices, can mean the difference between deterring cyberattacks and being able to contain them, and total submission to the aggressor.

At a government level, updating national cybersecurity strategies, introducing transparent mechanisms to control their implementation, fostering ICT-friendly regulatory environments, and preventing “brain drain” would allow CEE governments to better tackle cybersecurity concerns. In addition, promoting regional and international cooperation initiatives would generate synergies and help provide tailored regional solutions, particularly in the CEE region.

Looking to the future, and following the first steps taken at the 2017 CEE Innovators Summit, projects like The Digital Three Seas Initiative would allow for the creation of common security models and standards, cross-border cyber infrastructure projects like the 3 Seas Digital Highway, and further cooperation in countering information warfare. Fostering regional cooperation through institutions like the CECSP, and promoting public-private initiatives like the Digital Three Seas Initiative, would allow CEE countries to become policy entrepreneurs and assume a leading role in the European debate about cybersecurity (The Kosciuszko Institute 2018).

In the digital era, CEE countries face an increase in the number and disruption potential of cyberattacks directed against the public and private sectors. In order to address cybersecurity challenges, CEE countries should focus on developing and updating their national cybersecurity strategies and achieving further regional and international cooperation in ICT security. Only then will CEE countries fully exploit the potential for growth and development that digitisation provides.

References

Atlantic Council. NATO Updates Policy: Offers Members Article 5 Protection Against Cyber Attacks. 30 June 2014. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/natosource/nato-updates-policy-offers-members-article-5-protection-against-cyber-attacks/.

CSIS. The Kremlin Playbook. Understanding Russian Influence in Central and Eastern Europe. Washington: Center for Strategic & International Studies and CSD Economics Program, 2016.

Digital McKinsey. The Rise of Digital Challengers: How digitization can become the next growth engine for Central and Eastern Europe. McKinsey & Company, 2018.

ENISA. CSIRT Capabilities and Maturity History. 2021c. https://www.enisa.europa.eu/topics/csirts-in-europe/csirt-capabilities/baseline-capabilities.

—. CSIRTs by Country – Interactive Map. 2021b. https://www.enisa.europa.eu/topics/csirts-in-europe/csirt-inventory/certs-by-country-interactive-map#country=Czech%20Republic (accessed April 18, 2021).

ENISA. ENISA Threat Landscape 2020 – Main Incidents From January 2019 to April 2020. Annual Report, Attiki, Greece: European Union Agency for Cybersecurity, 2020a.

—. National Cyber Security Strategies – Interactive Map. 2021a. https://www.enisa.europa.eu/topics/national-cyber-security-strategies/ncss-map/national-cyber-security-strategies-interactive-map (accessed February 2021).

—. NIS Directive. 2021c. https://www.enisa.europa.eu/topics/nis-directive?tab=details.

ENISA. NIS Investments Report. ENISA, 2020b.

EUISS. Hacks, leaks and disruptions. Russian cyber strategies. Paris: Chaillot Papers Nº 148, 2018.

European Commission. EU Cybersecurity plan to protect open internet and online freedom and opportunity. 7 February 2013. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_13_94.

European Parliament Research Service. “Cyber: How big is the threat.” 2019.

EUROSTAT. Eurostat Digital Economy and Society Database. 2021. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/digital-economy-and-society/data/database?p_p_id=NavTreeportletprod_WAR_NavTreeportletprod_INSTANCE_pgrsK5zx6I84&p_p_lifecycle=0&p_p_state=normal&p_p_mode=view (accessed March 2021).

Ilves, Luukas K. , Timothy J. Evans, Frank J. Cilluffo, and Alec A. Nadeau. “European Union and NATO Global Cybersecurity Challenges: A Way Forward.” PRISM Volume 6, No.2, 2016: 127-141.

Legal Week Intelligence, CMS Law. “The Cybersecurity Challenge in Central and Eastern Europe.” 2018.

NATO. NATO will defend itself. 27 August 2019. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_168435.htm?selectedLocale=en (accessed April 2021).

NordVPN. “Cyber Risk Index.” 2020. https://s1.nordcdn.com/nord/misc/0.13.0/vpn/brand/NordVPN-cyber-risk-index-2020.pdf.

OECD. Internet Access (indicator). 2021a. https://data.oecd.org/ict/internet-access.htm (accessed March 2021).

—. Mobile Broadband Subscriptions. 2021b. https://data.oecd.org/broadband/mobile-broadband-subscriptions.htm (accessed March 2021).

Reuters. NATO cyber command to be fully operational in 2023. 16 October 2018. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-nato-cyber/nato-cyber-command-to-be-fully-operational-in-2023-idUSKCN1MQ1Z9.

STATISTA. Number of cyber security incidents handled by CERT in Poland from 1996 to 2019. July 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1028557/poland-cybersecurity-incidents/ (accessed February 2021).

—. Share of electronic devices infected with malware in Central and Eastern Europe in 2020. March 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1120059/electronic-devices-infected-with-malware-cee-region/ (accessed February 2021).

—. Size of the cybersecurity market worldwide, from 2017 to 2023. September 2018. https://www.statista.com/statistics/595182/worldwide-security-as-a-service-market-size/ (accessed February 2021).

The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies. “Cybersecurity: Ensuring awareness and resilience of the private sector across Europe in face of mounting cyber risks.” Study for the European Economic and Social Committee (EESC), The Hague, 2018.

The Kosciuszko Institute. “Cyber Threat Report CEE 2018, CYBERSEC Hub.” Edited by Robert Siudak. European Cybersecurity Market, Vol Vol 2, no. 3-4 (2018): 24-30.

The Kosciuszko Institute. The Digital 3 Seas Initiative: a Call for a Cyber Upgrade of Regional Cooperation. White Paper, Krakow, Poland: The Kosciuszko Institute Policy Brief, 2018.

Tikos, Anita, and Csaba Krasznay. Cybersecurity in the V4 Countries – A Cross-Border Case Study. Budapest: CEE eDem and eGov Days 2019, 2019, 163-174.

DATA SHEETS

Data sheet 1. Cybersecurity market revenues.

| Published by | Statista |

| Publication date | September 2018 |

| Original source | marketsandmarkets.com |

| Survey period | 2017 |

| ID | 595182 |

| Access data | |

| Cybersecurity market revenues worldwide 2017-2023 (in billion USD) | |

| 2017 | 137.63 |

| 2018* | 151.67 |

| 2019* | 167.14 |

| 2020* | 184.19 |

| 2021* | 202.97 |

| 2022* | 223.68 |

| 2023* | 248.26 |

Data sheet 2. Persons employed using computers with access to the World Wide Web.

| Extracted on | 04/03/2021 221936 | |||||||||

| Source of data | Eurostat | |||||||||

| INDIC_IS | Persons employed using computers with access to World Wide Web | |||||||||

| UNIT | Percentage of total employment | |||||||||

| SIZEN_R2 | All enterprises, without financial sector (10 persons employed or more) | |||||||||

| GEO/TIME | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

| EU | 43 | 44 | 46 | 46 | 48 | 49 | 50 | 53 | 54 | 56 |

| Belgium | 50 | 50 | 53 | 55 | 56 | 59 | 59 | 65 | ||

| Bulgaria | 21 | 22 | 24 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 34 |

| Czechia | 33 | 34 | 36 | 38 | 37 | 37 | 42 | 43 | 46 | 49 |

| Denmark | – | 64 | 67 | 71 | 71 | 73 | 73 | 75 | 77 | 77 |

| Germany | 52 | 52 | 51 | 52 | 52 | 53 | 54 | 58 | 59 | 59 |

| Estonia | 44 | 44 | 45 | 42 | 42 | 44 | 46 | 48 | 47 | 51 |

| Ireland | 45 | 46 | 49 | 46 | 46 | 52 | 51 | 54 | 55 | 59 |

| Greece | 33 | 33 | 37 | 37 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 45 |

| Spain | 43 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 49 | 50 | 51 | 51 | 52 | 56 |

| France | 46 | 45 | 49 | 51 | 53 | 54 | 55 | 61 | 62 | 61 |

| Croatia | 37 | 38 | 45 | 42 | 45 | 44 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 50 |

| Italy | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 41 | 43 | 45 | 48 | 50 | 53 |

| Cyprus | 36 | 36 | 37 | 40 | 39 | 41 | 42 | 43 | 43 | 46 |

| Latvia | 38 | 39 | 40 | 41 | – | 41 | 42 | 44 | 44 | 44 |

| Lithuania | 37 | 39 | 40 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 43 | 44 | 47 | 55 |

| Luxembourg | 53 | 55 | 53 | 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 46 | 47 | 53 |

| Hungary | 26 | 33 | 33 | 35 | 34 | 37 | 39 | 41 | 42 | 45 |

| Malta | 34 | 37 | 39 | 43 | 46 | 44 | 45 | 45 | 50 | 52 |

| Netherlands | 57 | 57 | 58 | 62 | 61 | 63 | 69 | 69 | 69 | 72 |

| Austria | – | 43 | 44 | 47 | 52 | 53 | 55 | 55 | 58 | 63 |

| Poland | 35 | 36 | 37 | 36 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 40 | 43 | 50 |

| Portugal | 31 | 32 | 35 | 35 | 36 | 36 | 38 | 37 | 38 | 43 |

| Romania | 28 | 26 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 28 | 32 | 34 | 31 | 35 |

| Slovenia | 45 | 48 | 48 | 47 | 48 | 51 | 51 | 53 | 52 | 54 |

| Slovakia | 37 | 39 | 40 | 38 | 39 | 41 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 48 |

| Finland | 65 | 65 | 64 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 72 | 74 | 80 |

| Sweden | 65 | 69 | 71 | 70 | 72 | 73 | 75 | 76 | 82 | 83 |

| Norway | 66 | 67 | 66 | 64 | 67 | 70 | 71 | 69 | 72 | 82 |

| United Kingdom | – | 51 | 53 | 54 | 56 | 56 | 57 | 60 | 61 | – |

Data sheet 3. Companies using any social media.

| Extracted on | 08/03/2021 112149 | |||||

| Source of data | Eurostat | |||||

| INDIC_IS | ||||||

| UNIT | Percentage of enterprises | |||||

| SIZEN_R2 | ||||||

| GEO/TIME | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2019 | |

| EU | 34 | 37 | 42 | 45 | 50 | |

| Belgium | – | 45 | 53 | 58 | 71 | |

| Bulgaria | 28 | 30 | 32 | 34 | 34 | |

| Czechia | – | 25 | 34 | 36 | 47 | |

| Denmark | 49 | 56 | 64 | 68 | 75 | |

| Germany | 33 | 38 | 47 | 45 | 48 | |

| Estonia | 28 | 33 | 39 | 40 | 49 | |

| Ireland | 60 | 64 | 66 | 68 | 71 | |

| Greece | 38 | 37 | 44 | 50 | 55 | |

| Spain | 37 | 40 | 44 | 51 | 53 | |

| France | – | 30 | 36 | 41 | 50 | |

| Croatia | 37 | 38 | 42 | 45 | 52 | |

| Italy | 32 | 37 | 39 | 44 | 47 | |

| Cyprus | 52 | 57 | 64 | 67 | 73 | |

| Latvia | 19 | 28 | 26 | 30 | 41 | |

| Lithuania | 36 | 42 | 45 | 50 | 55 | |

| Luxembourg | 36 | 39 | 49 | 54 | 62 | |

| Hungary | 26 | 29 | 34 | 38 | 38 | |

| Malta | 66 | 72 | 71 | 73 | 84 | |

| Netherlands | 58 | 63 | 65 | 68 | 74 | |

| Austria | 41 | 42 | 50 | 53 | 60 | |

| Poland | 22 | 22 | 25 | 27 | 37 | |

| Portugal | 39 | 38 | 44 | 46 | 50 | |

| Romania | 22 | 25 | 30 | 35 | 33 | |

| Slovenia | 39 | 42 | 46 | 47 | 50 | |

| Slovakia | 29 | 34 | 34 | 39 | 42 | |

| Finland | 46 | 50 | 60 | 63 | 71 | |

| Sweden | 48 | 53 | 58 | 65 | 72 | |

| Norway | 53 | 60 | 68 | 72 | 76 | |

| United Kingdom | 44 | 54 | 59 | 63 | 72 | |

Data sheet 4. Companies which have ERP software packages to share information between different functional areas.

| Last update | 08/02/2021 110124 | ||||||

| Extracted on | 04/03/2021 222817 | ||||||

| Source of data | Eurostat | ||||||

| INDIC_IS | Enterprises who have ERP software package to share information between different functional areas | ||||||

| UNIT | Percentage of enterprises | ||||||

| SIZEN_R2 | All enterprises, without financial sector (10 persons employed or more) | ||||||

| GEO/TIME | 2010 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2017 | 2019 |

| EU | 23 | 24 | 29 | 34 | 38 | 36 | 36 |

| Belgium | 40 | 33 | 41 | 47 | 50 | 54 | 53 |

| Bulgaria | 11 | 20 | 20 | 27 | 25 | 23 | 23 |

| Czechia | 21 | 24 | 23 | 28 | 30 | 28 | 38 |

| Denmark | 29 | 33 | 33 | 42 | 47 | 40 | 50 |

| Germany | 29 | 24 | 30 | 35 | 56 | 38 | 29 |

| Estonia | 7 | 10 | 15 | 17 | 22 | 28 | 26 |

| Ireland | 20 | 19 | 22 | 23 | 25 | 28 | 28 |

| Greece | 36 | – | 37 | 40 | 37 | 37 | 38 |

| Spain | 22 | 22 | 31 | 36 | 35 | 46 | 43 |

| France | 24 | 33 | 33 | 35 | 39 | 38 | 48 |

| Croatia | 15 | 19 | 28 | – | 29 | 26 | 26 |

| Italy | 22 | 21 | 27 | 37 | 36 | 37 | 35 |

| Cyprus | 17 | 21 | 28 | 36 | 43 | 35 | 33 |

| Latvia | 8 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 16 | 25 | 32 |

| Lithuania | 11 | 23 | 40 | 34 | 40 | 47 | 48 |

| Luxembourg | 21 | 23 | 36 | 39 | 39 | 41 | 41 |

| Hungary | 8 | 9 | 13 | 16 | 16 | 14 | 14 |

| Malta | 18 | 24 | 25 | 31 | 30 | 29 | 32 |

| Netherlands | 22 | 26 | 34 | 40 | 45 | 48 | 48 |

| Austria | 25 | 26 | 32 | 45 | 41 | 40 | 43 |

| Poland | 11 | 13 | 17 | 22 | 21 | 26 | 29 |

| Portugal | 26 | 31 | 32 | 40 | 44 | 40 | 42 |

| Romania | 19 | 20 | 15 | 21 | 22 | 22 | 23 |

| Slovenia | 21 | 28 | 28 | 30 | 33 | 30 | 33 |

| Slovakia | 17 | 20 | 31 | 28 | 30 | 31 | 31 |

| Finland | 28 | 33 | 37 | 39 | 37 | 39 | 43 |

| Sweden | 35 | 38 | 45 | 43 | – | 31 | 37 |

| Norway | 19 | 20 | 25 | 34 | 32 | 30 | 34 |

| United Kingdom | 6 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 17 | 19 | 24 |

Data sheet 5. Household internet access.

| c | ||||||||||

| https://data.oecd.org/ict/internet-access.htm | ||||||||||

| Percentage | ||||||||||

| TIME | CZE | POL | SVK | HUN | LTU | |||||

| 2005 | 19.05 | 30.44 | 22.97 | 22.12 | 15.78 | |||||

| 2006 | 29.25 | 35.94 | 26.58 | 31.65 | 34.51 | |||||

| 2007 | 35.12 | 40.98 | 46.11 | 37.72 | 44.36 | |||||

| 2008 | 45.86 | 47.6 | 58.34 | 46.63 | 50.94 | |||||

| 2009 | 54.18 | 58.59 | 62.23 | 53.42 | 60 | |||||

| 2010 | 60.52 | 63.44 | 67.48 | 58.41 | 60.58 | |||||

| 2011 | 66.63 | 66.64 | 70.78 | 63.22 | 60.14 | |||||

| 2012 | 72.55 | 70.49 | 75.44 | 66.81 | 60.12 | |||||

| 2013 | 72.62 | 71.9 | 77.91 | 69.66 | 64.73 | |||||

| 2014 | 77.99 | 74.76 | 78.35 | 73.06 | 65.97 | |||||

| 2015 | 78.98 | 75.78 | 79.48 | 75.64 | 68.26 | |||||

| 2016 | 81.65 | 80.45 | 80.52 | 79.18 | 71.75 | |||||

| 2017 | 83.24 | 81.88 | 81.33 | 82.35 | 74.97 | |||||

| 2018 | 86.36 | 84.19 | 80.84 | 83.31 | 78.38 | |||||

| 2019 | 87 | 86.75 | 82.19 | 86.2 | 81.52 | |||||

Data sheet 6. Mobile broadband subscriptions.

| Mobile broadband subscriptions (per 100 inhabitants) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| https://data.oecd.org/broadband/mobile-broadband-subscriptions.htm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Data sheet 7. Frequency of daily computer use by individuals.

| Extracted on | 08/03/2021 201801 | |||||||||

| Source of data | Eurostat | |||||||||

| INDIC_IS | Frequency of computer use daily | |||||||||

| UNIT | Percentage of individuals | |||||||||

| IND_TYPE | All Individuals | |||||||||

| GEO/TIME | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2017 |

| EU | 44 | 48 | 51 | 54 | 57 | 58 | 60 | 61 | 62 | 62 |

| Belgium | 54 | 55 | 59 | 64 | 68 | 68 | 70 | 71 | 71 | 72 |

| Bulgaria | 25 | 28 | 34 | 35 | 39 | 42 | 43 | 46 | 47 | 52 |

| Czechia | 33 | 37 | 40 | 44 | 45 | 23 | 54 | 60 | 62 | 66 |

| Denmark | 69 | 73 | 75 | 78 | 80 | 81 | 83 | 82 | 82 | 83 |

| Germany | 57 | 61 | 63 | 67 | 68 | 69 | 71 | 73 | 74 | 74 |

| Estonia | 45 | 47 | 54 | 59 | 60 | 61 | 64 | 72 | 75 | 74 |

| Ireland | 43 | 47 | 46 | 52 | 58 | 60 | 61 | 63 | 63 | 62 |

| Greece | 28 | 30 | 32 | 35 | 40 | 42 | 47 | 49 | 54 | 57 |

| Spain | 36 | 39 | 43 | 47 | 49 | 52 | 51 | 51 | 50 | 47 |

| France | 49 | 54 | 57 | 60 | 63 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 64 | 61 |

| Croatia | 31 | 32 | 39 | 43 | 46 | 49 | 54 | 55 | 55 | 51 |

| Italy | 38 | 41 | 44 | 49 | 50 | 52 | 54 | 55 | 57 | 52 |

| Cyprus | 34 | 34 | 42 | 47 | 49 | 51 | 55 | 57 | 61 | 63 |

| Latvia | 41 | 45 | 48 | 50 | 54 | 58 | 60 | 62 | 63 | 66 |

| Lithuania | 34 | 41 | 45 | 47 | 47 | 49 | 53 | 57 | 56 | 61 |

| Luxembourg | 62 | 68 | 75 | 77 | 78 | 81 | 81 | 82 | 81 | 82 |

| Hungary | 44 | 48 | 49 | 51 | 56 | 59 | 62 | 65 | 62 | 66 |

| Malta | 37 | 39 | 47 | 51 | 57 | 58 | 60 | 62 | 66 | 68 |

| Netherlands | 70 | 71 | 76 | 78 | 80 | 81 | 80 | 81 | 80 | 80 |

| Austria | 55 | 58 | 56 | 59 | 63 | 64 | 65 | 64 | 67 | 66 |

| Poland | 34 | 38 | 42 | 45 | 48 | 49 | 48 | 52 | 53 | 60 |

| Portugal | 35 | 35 | 39 | 42 | 45 | 47 | 50 | 51 | 53 | 51 |

| Romania | 18 | 20 | 23 | 24 | 26 | 31 | 34 | 34 | 38 | 45 |

| Slovenia | 43 | 44 | 51 | 57 | 57 | 56 | 59 | 58 | 60 | 64 |

| Slovakia | 46 | 55 | 56 | 63 | 59 | 61 | 63 | 63 | 61 | 68 |

| Finland | 65 | 69 | 69 | 74 | 77 | 79 | 79 | 78 | 79 | 78 |

| Sweden | 68 | 72 | 76 | 78 | 81 | 79 | 79 | 79 | 74 | 80 |

| Norway | 73 | 75 | 78 | 83 | 83 | 87 | 85 | 85 | 79 | 83 |

| United Kingdom | 58 | 61 | 67 | 70 | 72 | 74 | 75 | 78 | 75 | 78 |

Data sheet 8. Internet use interaction with public authorities in the last 12 months.

| Extracted on | 08/03/2021 153139 | |||||||||

| Source of data | Eurostat | |||||||||

| INDIC_IS | Internet use interaction with public authorities (last 12 months) | |||||||||

| UNIT | Percentage of individuals | |||||||||

| IND_TYPE | All Individuals | |||||||||

| GEO/TIME | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

| EU | 41 | 44 | 42 | 46 | 46 | 48 | 49 | 51 | 53 | 56 |

| Belgium | 47 | 50 | 50 | 55 | 52 | 55 | 55 | 56 | 59 | 61 |

| Bulgaria | 25 | 27 | 23 | 21 | 18 | 19 | 21 | 22 | 25 | 27 |

| Czechia | 42 | 31 | 29 | 37 | 32 | 36 | 46 | 53 | 54 | 57 |

| Denmark | 81 | 83 | 85 | 84 | 88 | 88 | 89 | 92 | 92 | 91 |

| Germany | 50 | 51 | 49 | 53 | 53 | 55 | 53 | 57 | 59 | 66 |

| Estonia | 53 | 54 | 48 | 51 | 81 | 77 | 78 | 79 | 80 | 80 |

| Ireland | 44 | 49 | 45 | 51 | 50 | 52 | 55 | 54 | 61 | 62 |

| Greece | 27 | 34 | 36 | 45 | 46 | 49 | 47 | 50 | 52 | 53 |

| Spain | 38 | 44 | 44 | 49 | 49 | 50 | 52 | 57 | 58 | 63 |

| France | 57 | 61 | 60 | 64 | 63 | 66 | 68 | 71 | 75 | – |

| Croatia | 17 | 26 | 25 | 32 | 35 | 36 | 32 | 36 | 33 | 41 |

| Italy | 22 | 19 | 21 | 23 | 24 | 24 | 25 | 24 | 23 | – |

| Cyprus | 29 | 30 | 30 | 41 | 34 | 38 | 42 | 42 | 50 | 53 |

| Latvia | 41 | 47 | 35 | 54 | 52 | 69 | 69 | 66 | 70 | 76 |

| Lithuania | 29 | 36 | 34 | 41 | 44 | 45 | 48 | 51 | 55 | 58 |

| Luxembourg | 60 | 61 | 56 | 67 | 70 | 76 | 75 | 63 | 60 | 63 |

| Hungary | 38 | 42 | 37 | 49 | 42 | 48 | 47 | 53 | 53 | 60 |

| Malta | 37 | 41 | 32 | 41 | 42 | 45 | 46 | 47 | 50 | 55 |

| Netherlands | 62 | 67 | 79 | 75 | 75 | 76 | 79 | 82 | 81 | 86 |

| Austria | 51 | 53 | 54 | 59 | 57 | 60 | 62 | 66 | 70 | 72 |

| Poland | 28 | 32 | 23 | 27 | 27 | 30 | 31 | 35 | 40 | 42 |

| Portugal | 37 | 39 | 38 | 41 | 43 | 45 | 46 | 42 | 41 | 45 |

| Romania | 7 | 31 | 5 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 12 | 13 |

| Slovenia | 46 | 48 | 52 | 53 | 45 | 45 | 50 | 54 | 53 | 67 |

| Slovakia | 48 | 42 | 33 | 57 | 51 | 48 | 47 | 51 | 59 | 62 |

| Finland | 68 | 70 | 69 | 80 | 79 | 82 | 83 | 83 | 87 | 88 |

| Sweden | 74 | 78 | 78 | 81 | 73 | 78 | 84 | 83 | 86 | 86 |

| Norway | 78 | 78 | 76 | 82 | 81 | 85 | 84 | 90 | 87 | 92 |

| Switzerland | – | – | – | 71 | – | – | 75 | – | 75 | – |

| United Kingdom | 40 | 43 | 41 | 51 | 49 | 53 | 49 | 59 | 63 | 57 |

Data sheet 9. Internet use submitting completed forms in the last 12 months.

| Extracted on | 04/03/2021 221806 | |||||||||

| Source of data | Eurostat | |||||||||

| INDIC_IS | Internet use submitting completed forms (last 12 months) | |||||||||

| UNIT | Percentage of individuals | |||||||||

| IND_TYPE | All Individuals | |||||||||

| GEO/TIME | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

| EU | 20 | 22 | 21 | 25 | 25 | 27 | 29 | 33 | 36 | 38 |

| Belgium | 26 | 29 | 32 | 36 | 34 | 35 | 37 | 37 | 40 | 41 |

| Bulgaria | 10 | 11 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 15 |

| Czechia | 33 | 13 | 7 | 11 | 10 | 12 | 14 | 26 | 25 | 29 |

| Denmark | 64 | 69 | 66 | 66 | 69 | 71 | 71 | 73 | 74 | 68 |

| Germany | 15 | 15 | 14 | 16 | 17 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 21 | 26 |

| Estonia | 36 | 33 | 30 | 32 | 71 | 68 | 70 | 71 | 74 | 75 |

| Ireland | 34 | 38 | 36 | 46 | 46 | 48 | 52 | 49 | 55 | 54 |

| Greece | 13 | 18 | 20 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 24 | 24 | 28 | 27 |

| Spain | 17 | 22 | 24 | 29 | 30 | 32 | 33 | 41 | 47 | 49 |

| France | 36 | 40 | 32 | – | 42 | 49 | 53 | 59 | 64 | – |

| Croatia | 6 | 9 | 10 | 13 | 15 | 17 | 15 | 16 | 19 | 25 |

| Italy | 8 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 15 | 14 | – |

| Cyprus | 13 | 15 | 10 | 19 | 17 | 22 | 24 | 26 | 34 | 40 |

| Latvia | 22 | 17 | 13 | 19 | 29 | 31 | 39 | 50 | 56 | 63 |

| Lithuania | 24 | 29 | 28 | 31 | 31 | 33 | 37 | 41 | 43 | 45 |

| Luxembourg | 25 | 25 | 25 | 35 | 35 | 35 | 36 | 31 | 36 | 36 |

| Hungary | 18 | 20 | 18 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 29 | 37 | 39 | 37 |

| Malta | 16 | 17 | 13 | 20 | 22 | 19 | 20 | 23 | 28 | 35 |

| Netherlands | 48 | 50 | 57 | 57 | 53 | 55 | 56 | 59 | 58 | 73 |

| Austria | 24 | 26 | 28 | 30 | 31 | 33 | 37 | 45 | 47 | 50 |

| Poland | 9 | 11 | 11 | 15 | 16 | 19 | 21 | 25 | 31 | 34 |

| Portugal | 28 | 27 | 27 | 29 | 28 | 29 | 32 | 30 | 30 | 34 |

| Romania | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 7 |

| Slovenia | 14 | 15 | 21 | 21 | 18 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 21 | 32 |

| Slovakia | 11 | 17 | 16 | 17 | 13 | 15 | 15 | 16 | 18 | 19 |

| Finland | 40 | 45 | 45 | 56 | 58 | 60 | 66 | 65 | 72 | 74 |

| Sweden | 42 | 45 | 46 | 50 | 45 | 48 | 72 | 74 | 77 | 74 |

| Norway | 53 | 51 | 50 | 56 | 58 | 62 | 60 | 66 | 68 | 81 |

| Switzerland | – | – | – | 44 | – | – | 43 | – | 45 | – |

| United Kingdom | 23 | 26 | 22 | 34 | 32 | 34 | 35 | 45 | 51 | 39 |

Data sheet 10. Number of cybersecurity incidents handled by CERT in Poland from 1996 to 2019.

| Statistic as Excel data file | |||

| Number of cyber security incidents handled by CERT* in Poland from 1996 to 2019 | |||

| Access data | |||

| Source | CERT Polska | ||

| Conducted by | CERT Polska | ||

| Survey period | 1996 to 2019 | ||

| Region | Poland | ||

| Published by | CERT Polska | ||

| Publication date | July 2020 | ||

| Original source | Krajobraz bezpieczestwa polskiego Internetu w 2019 roku, page 12 | ||

| ID | 1028557 | ||

| YEAR | CERT-HANDLED ATTACKS | ||

| 1996 | 50 | ||

| 1997 | 75 | ||

| 1998 | 100 | ||

| 1999 | 105 | ||

| 2000 | 126 | ||

| 2001 | 741 | ||

| 2002 | 1,013 | ||

| 2003 | 1,196 | ||

| 2004 | 1,222 | ||

| 2005 | 2,516 | ||

| 2006 | 2,427 | ||

| 2007 | 2,108 | ||

| 2008 | 1,796 | ||

| 2009 | 1,292 | ||

| 2010 | 674 | ||

| 2011 | 605 | ||

| 2012 | 1,082 | ||

| 2013 | 1,219 | ||

| 2014 | 1,282 | ||

| 2015 | 1,456 | ||

| 2016 | 1,926 | ||

| 2017 | 3,182 | ||

| 2018 | 3,739 | ||

| 2019 | 6,484 | ||

Data sheet 11. Company ICT security measures.

| ICT security measures implemented by companies | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Extracted on | 10.03.21 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source of data | Eurostat | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| SIZEN_R2 | All enterprises, without financial sector (10 persons employed or more) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| UNIT | Percentage of enterprises | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| YEAR | 2019 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| GEO/TIME | Updated Software | Data backup (different location) | Periodic ICT risk assessment | Company documents on ICT security | Compulsory training on ICT obligations | ICT obligations employee awareness | ICT security: own personnel | ICT security: external suppliers | ||||||||||||||||

| EU | 87 | 76 | 33 | 33 | 22 | 61 | 40 | 65 | ||||||||||||||||

| Belgium | 87 | 80 | 43 | 34 | 20 | 57 | 40 | 77 | ||||||||||||||||

| Bulgaria | 74 | 51 | 23 | 18 | 12 | 51 | 38 | 51 | ||||||||||||||||

| Czechia | 89 | 82 | 37 | 32 | 31 | 76 | 44 | 66 | ||||||||||||||||

| Denmark | 88 | 85 | 49 | 56 | 35 | 70 | 60 | 69 | ||||||||||||||||

| Germany | 95 | 89 | 34 | 37 | 17 | 68 | 43 | 68 | ||||||||||||||||

| Estonia | 71 | 64 | 23 | 27 | 42 | 55 | 41 | 54 | ||||||||||||||||

| Ireland | 89 | 85 | 54 | 54 | 35 | 76 | 50 | 61 | ||||||||||||||||

| Greece | 61 | 53 | 25 | 15 | 10 | 33 | 30 | 57 | ||||||||||||||||

| Spain | 86 | 82 | 28 | 33 | 21 | 54 | 38 | 67 | ||||||||||||||||

| France | 86 | 68 | 33 | 26 | 19 | 55 | 40 | 67 | ||||||||||||||||

| Croatia | 84 | 78 | 24 | 41 | 16 | 47 | 49 | 71 | ||||||||||||||||

| Italy | 89 | 79 | 34 | 34 | 35 | 73 | 31 | 66 | ||||||||||||||||

| Cyprus | 79 | 69 | 35 | 32 | 18 | 59 | 37 | 67 | ||||||||||||||||

| Latvia | 75 | 61 | 30 | 42 | 20 | 68 | 30 | 74 | ||||||||||||||||

| Lithuania | 80 | 68 | 24 | 36 | 21 | 67 | 46 | 64 | ||||||||||||||||

| Luxembourg | 87 | 79 | 31 | 27 | 21 | 52 | 46 | 63 | ||||||||||||||||

| Hungary | 82 | 59 | 14 | 17 | 10 | 48 | 32 | 45 | ||||||||||||||||

| Malta | 87 | 76 | 40 | 32 | 21 | 59 | 40 | 64 | ||||||||||||||||

| Netherlands | 92 | 86 | 53 | 42 | 18 | 56 | 48 | 74 | ||||||||||||||||

| Austria | 82 | 88 | 28 | 36 | 22 | 63 | 44 | 60 | ||||||||||||||||

| Poland | 81 | 57 | 24 | 23 | 32 | 49 | 34 | 69 | ||||||||||||||||

| Portugal | 90 | 74 | 41 | 28 | 27 | 54 | 46 | 75 | ||||||||||||||||

| Romania | 64 | 40 | 16 | 17 | 7 | 49 | 39 | 43 | ||||||||||||||||

| Slovenia | 77 | 62 | 21 | 35 | 15 | 53 | 37 | 61 | ||||||||||||||||

| Slovakia | 85 | 72 | 30 | 28 | 29 | 64 | 36 | 65 | ||||||||||||||||

| Finland | 94 | 83 | 60 | 44 | 25 | 66 | 65 | 62 | ||||||||||||||||

| Sweden | 91 | 83 | 52 | 52 | 26 | 66 | 57 | 59 | ||||||||||||||||

| Norway | 91 | 81 | 44 | 32 | 29 | 61 | 52 | 52 | ||||||||||||||||

| United Kingdom | 90 | 75 | 43 | 48 | 37 | 69 | 48 | 45 | ||||||||||||||||

Data Sheet 12. CERTs in Europe.

Number of public and private CERTs in Europe in 2017 and 2021

| Country | 2017 | 2021 |

| Bulgaria | 1 | 1 |

| Estonia | 2 | 2 |

| Croatia | 2 | 2 |

| Slovenia | 1 | 2 |

| Latvia | 1 | 2 |

| Cyprus | 1 | 2 |

| Ireland | 4 | 3 |

| Hungary | 3 | 3 |

| Malta | 2 | 3 |

| Finland | 5 | 5 |

| Greece | 4 | 6 |

| Lithuania | 6 | 8 |

| Belgium | 5 | 8 |

| Romania | 6 | 9 |

| Austria | 5 | 10 |

| Slovakia | 4 | 10 |

| Luxembourg | 10 | 11 |

| Denmark | 8 | 11 |

| Norway | – | 18 |

| Sweden | 12 | 20 |

| Poland | 6 | 24 |

| United Kingdom | 23 | 27 |

| Netherlands | 18 | 29 |

| Italy | 10 | 29 |

| France | 25 | 41 |

| Portugal | 5 | 42 |

| Germany | 33 | 47 |

| Czech Republic | 25 | 54 |

| Spain | 18 | 59 |