Brian F. G. Fabrègue – University of Zurich

Brian F. G. Fabrègue is Ph.D candidate in law at the University of Zurich and is currently working as Chief Legal Officer for a Swiss fintech company. His main areas of legal expertise are International Taxation, Financial Regulation and Corporate Law. He also holds an MBA, through which he specialized in Statistics and Econometrics. His research focuses mostly on smart development and has led him to analyze the entanglement between technology and law, particularly from a data privacy perspective, understanding legal frameworks and policies that govern the use of technology in urban planning. He is currently serving as Blue Europe think tank President, where he authored numerous articles in the fields of energy studies, economics, international relations, public policy and environmental issues.

Christiaan Vermorken – Université Libre de Bruxelles

Christiaan Vermorken is a lawyer, historian and political scientist with eight years’ experience in legal services, private law litigation, academic research and lecturing. He obtained a PhD in Political Science at the European University Institute and several Master’s Degrees, including a Master’s Degree in History at the University of Bologna and a Master’s Degree in Political Sciences, Peoples and Societies of Eastern Europe, Russia and the Caucasus at the University of Bruxelles. He is skilled in public policy analysis, legal and institutional history, military doctrine and foreign languages; having cooperated in the past with international institutions like the European Parliament.

This contribution is part of the book “The Dragon at the Gates of Europe: Chinese presence in the Balkans and Central-Eastern Europe” (more info here) and has been selected for open access publication on Blue Europe website for a wider reach. Citation:

Fabrègue, Brian F. G., and Christiaan Vermorken, Central and Eastern Europe between Brussels and Beijing: to BRI or not to BRI? in: Andrea Bogoni and Brian F. G. Fabrègue, eds., The Dragon at the Gates of Europe: Chinese Presence in the Balkans and Central-Eastern Europe, Blue Europe, Dec 2023: pp. 11-40. ISBN: 979-8989739806.

1. Introduction

The initiation of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013 marked a significant shift in China’s foreign policy toward a more resolutely assertive stance. Similarly, the establishment of the ‘16+1’ mechanism in 2012 aimed to expand economic and cultural bonds between Central and Eastern European (CEE) nations and China. While this scheme of cooperation preceded the Belt and Road Initiative by a year, it has since been integrated into the overarching framework of the BRI, with its objectives harmonized accordingly.[1] The CEE region occupies a pivotal position as a gateway connecting Asia and Europe, serving as a hub connecting the BRI’s maritime route through Greece and its land route through Poland. Furthermore, the CEE constitutes a substantial market, boasting over 110 million middle-income consumers.

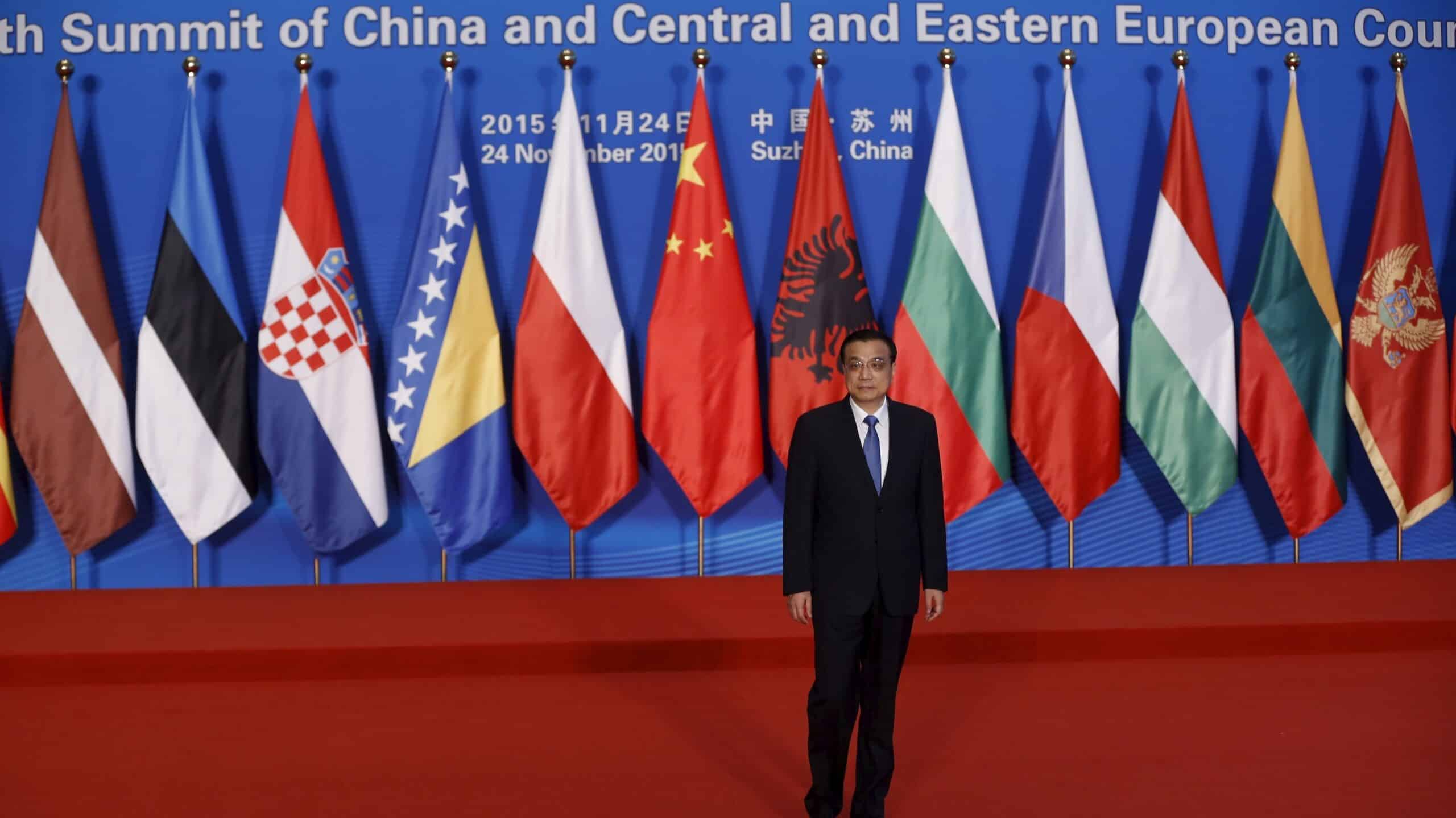

Initially encompassing 16 countries from the CEE region, the ‘16+1’ mechanism comprised 11 European Union (EU) member states (namely, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Croatia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia) and five candidate countries (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia). Of these, all but Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina are members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). The accession of Greece in 2019 led to the platform’s being renamed to ‘17 + 1’,[2] but it reverted to its previous name upon Lithuania’s decision to withdraw in May 2021.[3] It should also be mentioned that all participating countries have ratified the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) for the BRI and have consistently endorsed the initiative since its inception.[4]

After the breakout of the Russo-Ukrainian conflict and the declaration of a complex, yet “no-limits” friendship between China and Russia,[5] diplomatic relations between Brussels and Beijing deteriorated even further. Against this backdrop, Latvia and Estonia opted out from the 16+1 mechanism in August 2022, leaving only fourteen other states in the “X+1” format.[6] The Czech Republic finally followed suit in May 2023, declaring that “Prague is not an active member” of the 14+1.[7] Interestingly, all countries which withdrew or announced their inactivity from the X+1 group are also members of NATO and the European Union, indicating their reluctance to face criticism from Brussels.

Nevertheless, the original mandate of the X+1 mechanism was to facilitate linkages across various sectors of the economy, including infrastructure, transport, trade, and investments, while also fortifying cultural, educational, and tourism-related collaboration. In explicating China’s motivation behind engaging the CEE region, China’s regional involvement can be linked to a broader trend in its evolving global stature, with CEE partners serving as a land bridge geared toward the expansion of its industrial capacity and commercial footprint.[8]

Concerns have arisen that the X+1 mechanism, limited to the CEE region, may represent a “divide and conquer” strategy deployed by China vis-à-vis Europe.[9] These apprehensions are pervasive in both media and academia.[10] Nevertheless, the geopolitical landscape is inherently intricate, largely due to the involvement of major countries in the CEE region. While it is true that China’s has a role in international relations with CEE countries, the EU and the United States serve as a significant counterbalancing force limiting China’s sway in the region.[11] It should be noted that Chinese pledges of cooperation intended as a means to benefit less developed countries have evolved over a decade into a source of contention among the major powers.[12] For instance, the United States, in light of its mounting trade disputes with China, has assumed a more and more assertive posture marked by containment measures and increased engagement in Central and Eastern Europe. With this end in view, it has started to exert direct pressure to curtail China-CEE cooperation.[13]

Expanding upon Chinese economic practices, they do not inherently undermine or antagonize Europe but rather create a scenario in which Brussels’ influence may diminish in absolute terms if China and the CEE trade and economic relations grow.[14] However, it is a generally acknowledged opinion that China not only lacks the capacity but also the will to exert influence over CEE countries at the expense of the EU, demonstrating that the European community can assert its position through structural power.[15]

Many governments of EU member states and their general population have strong reservations about China’s benign intentions.[16] The EU, in particular, has adopted a more confrontational stance toward China, often questioning the motivations underpinning the cooperation between China and CEE countries.[17] The BRI and, by extension, the 16+1/17+1 mechanism, remain shrouded in ambiguity, provoking scepticism and a lack of confidence regarding China’s underlying objectives, with concerns that long-term economic collaboration could potentially ensnare the CEE region within China’s sphere of influence.[18],[19]

2. An overview of Chinese global strategy through the Belt and Road Initiative

On the 17th and 18th of October 2023, the third Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation took place in China, convening heads of state and representatives from the countries participating in the Chinese initiative. Notably, this Forum coincided with the 10th anniversary of the inception of the Belt and Road Initiative in 2013, initiated by Chinese President Xi Jinping. Attending the Forum were 23 heads of state, a decrease from the 37 present at the previous meeting in 2019. Additionally, representatives from more than 130 countries, primarily hailing from the so-called Global South, were in attendance.

The recalibration of the BRI involves a shift away from large-scale infrastructure projects in favour of endeavours centred on digitization, collaborative ventures in advanced sectors such as Artificial Intelligence (AI), and a strong emphasis on sustainability. To fund this altered trajectory, cooperation projects valued at over USD 97 billion were inked between China and participating nations during the Forum.[20]

A decade after its inception, the BRI has succeeded in garnering consensus, at least among the over 150 nations that have embraced it. Nevertheless, the anticipated objectives have not been entirely realized, as recipient countries have found the actual benefits to be somewhat lacking in addressing pressing concerns. Consequently, China has pursued revisions to enhance financial and environmental sustainability since the second forum held in 2019. However, these alterations have only been partially implemented, and even in the third forum, the adjustments leaned towards a more streamlined and sustainable initiative compared to its initial form. Initially conceived as a mechanism to connect China with Eurasian markets, the BRI has, over the course of a decade, transcended these geographical confines. According to the Belt and Road Portal, 152 countries have thus far enlisted in the Chinese project. Furthermore, during the past decade, BRI investments are estimated to have surpassed USD 1 trillion.[21]

Moreover, while remaining pivotal to China’s initiative to reshape the international order, Beijing has in recent years interlinked it with three global initiatives aimed at security, development, and civilization. These initiatives are known as the Global Development Initiative (GDI), the Global Security Initiative (GSI), and the Global Civilization Initiative (GCI), and they are positioned as China’s efforts to generate ‘public goods’ for the international community. From a Western perspective, the BRI has evolved into a symbol of China’s global outreach, aimed at exerting comprehensive control over trade routes, access to raw materials, and financial bonds with less affluent nations.

From a theoretical standpoint, the BRI has become an integral component of a broader strategy designed to promote a “community of shared destiny”. This Chinese concept postulates that China should serve as the advocate for a novel model of international relations founded on mutually beneficial cooperation among nations. These principles are conveyed through the historical allusion to the Silk Road: by invoking the Silk Road connections, there is an element of idealization, portraying it as a period of prosperity stemming from cross-cultural exchanges. The revitalization of Silk Road connections entails the promise of a return to prosperity through enhanced connectivity and the facilitation of Chinese investments within this framework.

The renovated structure of the Belt and Road Initiative after a decade

In 2015, the Chinese government outlined guidelines for the development of the BRI in the document “Vision and Actions on Jointly Building the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road”.[22] The BRI is divided into six main corridors,[23] building on existing agreements and develops mostly through Asia. The corridor most relevant to this discussion is the New Eurasian Land-Bridge, which starts in China’s Jiangsu province, then crosses Xinjiang and ends in the Netherlands, passing through Eastern Europe. There are also numerous projects aimed at improving maritime cooperation and connectivity. The Maritime Silk Road network has grown to include 113 ports in 43 different countries. However, these corridors are not binding for the creation of projects or cooperation within the initiative. Private actors that make up the complex machinery of the BRI often go beyond these initial guidelines for the development of the Silk Road, following their own economic and strategic interests.

In addition to the main strand of practical infrastructure application, two other branches of the BRI have developed in parallel over the years: the Health Silk Road and the Digital Silk Road. The former emerged during the pandemic and helped promote Beijing’s ‘vaccine diplomacy’, while the latter aims to improve connectivity in member countries through the use of Chinese-made technologies – such as Huawei’s 5G networks. While the prospect of an infrastructure network – particularly ports – has raised alarms about Chinese control of communication routes, the Health Silk Road has been read as an aggressive soft power move at a critical time. In particular, in the spring of 2020, EU High Commissioner for Foreign Policy Borrell accused China of engaging in a ‘battle of narratives’ aimed at portraying Europe as failing to come to the aid of the first countries hit by the pandemic while Beijing was presenting itself as a supportive actor. Similarly, criticism of Beijing-led digital connectivity should be seen in the context of US-China technological competition and Western fears that China is seeking technological dominance by controlling the development and standards of telecommunications infrastructure.

Chinese objectives behind the Belt and Road Initiative

The Chinese objectives in creating the BRI are economic and political. On the economic front, the BRI aims to strengthen trade and industrial relations among its member countries in order to (1) find an outlet for Chinese industrial overcapacity, (2) find new investment opportunities that are more profitable than the now saturated Chinese markets, and (3) find new markets for Chinese goods – especially those produced in the interior and far-flung regions – and secure access to raw materials.[24]

The BRI has thus favoured Beijing’s investment in sectors that are no longer profitable at home and in key natural energy resources such as coal, oil, and gas. It is, therefore, no coincidence that some of the countries most affected by the BRI are Russia, Central Asia, and the Middle East.[25]

Politically, the BRI aims to create a network of countries that share a proposal to revise international economic relations according to Beijing’s vision. This argument, which has been promoted since 2013, actually anticipates the explicit calls for a revision of the international order that have become more frequent since Russia’s war in Ukraine,[26] and which have found application in the enlargement of the BRICS – the body originally formed by Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa – as well as in the strengthening of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), a regional military body led by Russia and China.

Future prospects for the Belt and Road Initiative

From a domestic perspective, the main problems to the BRI’s future are the resources available for investment – which are diminishing with the slowdown in China – and the return on investment in countries at risk. According to the World Bank, China was the largest public creditor of developing countries in 2020, with more than EUR 110 billion still to be received, compared to about EUR 55 billion of the 22 Paris Club countries and another EUR 25 billion from other countries.[27] However, Beijing is having particular problems collecting the money lent by Chinese banks. Indeed, in recent years, following the pandemic and the shocks caused by recent international conflicts, many countries in the Global South have tried to renegotiate the terms of their debt with the Chinese government, causing economic problems for the Chinese companies involved.[28] Unsurprisingly, therefore, new projects are expected to be both smaller and less risky. Indeed, the high-risk investments that only China dared to make while Western institutions shunned them have proven to be unsolvable, so that now even Beijing has had to turn to safer opportunities, both geographically (Latin America instead of Africa) and in terms of the type of investment.

On the international side, however, a narrative has emerged that strongly counters the rise of Chinese external projection. Since the BRI was proposed, there have been numerous attempts to compete with the Chinese plan, especially in terms of infrastructure. The most important are the European Union’s Global Gateway, the US and G7’s Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII, formerly Build Back Better World) and the India-Middle East-Europe Corridor (IMEC), while at the level of individual states, the UK government’s Clean Green Initiative and Japan’s Partnership for Quality Infrastructure stand out.

3. The strategic Chinese view of Central-Eastern European countries

In contrast to the European Union’s geographical reach, a substantial proportion of Chinese infrastructure initiatives are strategically concentrated within the realm of Central and Eastern Europe. This distinct geographical focus significantly complicates China’s multifaceted engagement with this region. While it remains true that a majority of Chinese Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) is directed toward the core EU member states as can be seen in Table 1 below, it is crucial to note that infrastructure undertakings are predominantly executed in the European periphery, specifically Central and Eastern Europe. This observation is substantiated by empirical evidence.[29] Additionally, the totalling amount of FDIs from 2000 to 2021 is irrisory if compared to other sources of foreign investments in the EU.

Nevertheless, it is vital to comprehend that these infrastructure projects do not fall under the scope of traditional investments in the financial sense. Rather, they constitute financial loans, reminiscent of analogous Chinese initiatives in the African[30] and Asian[31] contexts. These loans are inherently linked to infrastructure projects delegated to Chinese contractors, often reliant on Chinese resources and labour.[32]

Table 1. Total amount of Chinese FDIs in selected EU countries for comparison (from 2000 to 2021)

| Country | FDI (in billions of EUR) |

| Germany | 30.1 |

| Italy | 16 |

| France | 15.7 |

| Netherlands | 13.5 |

| Finland | 13 |

| Hungary | 2.9 |

| Poland | 2.4 |

| Romania | 1.4 |

| Czech Republic | 1.3 |

| Slovenia | 1.3 |

| Croatia | 0.4 |

| Slovakia | 0.3 |

| Bulgaria | 0.3 |

| Estonia | 0.2 |

| Lithuania | 0.1 |

| Latvia | Less than 0.1 |

China’s strategic interest in this region is further fortified by two interrelated factors. Firstly, the European Union is China’s paramount export market, accentuating the two entities’ mutual economic interdependence. Secondly, China aspires for its corporate entities to compete for infrastructure projects funded by European sources within the EU.

The heightened importance ascribed to the Western Balkans, for instance, where a substantial proportion of these infrastructure initiatives are concentrated, stems from its pivotal role in bridging Central and Eastern Europe with the Mediterranean Sea. This geographical nexus facilitates maritime access to Europe’s inner core and underscores the strategic significance of this region. China’s strategic interest notably extends to the expansion of railway connectivity, as exemplified by its growing involvement in the Western Balkans region.[34]

Nonetheless, it is essential to acknowledge that the Chinese infrastructure endeavours in Europe have encountered mounting criticism, particularly from the vantage point of Western Europe. This arises partly due to perceived inaction and passivity on the part of the European Union in the region. As a result, China’s breadth of action has expanded over the past decade, culminating in the accrual of economic and political influence through loans and major projects across the region.[35] This strategic vacuum created by the European Union’s perceived inertia may provide further openings for China in the coming years, potentially compromising the European Union’s developmental objectives.[36]

One illustrative flagship project in the region is the Belgrade-Budapest railway, which is yet to be completed. While this project is a pivotal endeavour in respect to connectivity, it’s success hinges on the concomitant completion of other railway segments leading to the port of Piraeus. Moreover, it constitutes just one among several potential transit options and trade routes for Chinese enterprises. Other northern Adriatic Sea ports, such as Trieste in Italy, Koper in Slovenia, and Rijeka in Croatia, offer viable alternatives. Southeast Europe is also accessible via rail connections from China through Turkey and Poland, the latter boasting the most extensive array of block train connections from China via Russia and Central Asia. Furthermore, China’s interests extend beyond this immediate region to encompass Western European ports, including Valencia, Zeebrugge, Antwerp, and Rotterdam.[37]

Chinese State-Owned Enterprises and corporations may therefore be employing the Western Balkans as a training ground to cultivate expertise for forthcoming projects within the European Union, a strategic manoeuvre which is bound to augment the pool of Chinese enterprises equipped to compete for future bids and projects, ultimately fostering a competitive landscape. While this phenomenon is not necessarily a cause for alarm, it holds potential long-term benefits for Chinese firms, allowing these enterprises to operate with the financial backing of the European Union, among other sources.

In summary, the geopolitical significance of the Central-Eastern European region stems from its unique location, facilitating a vital connection between the Mediterranean Sea and Western Europe. This significance is further compounded by the region’s underdeveloped or lacking infrastructure, limited financial resources, and its close proximity to the European Union. These factors collectively serve as magnets for Chinese interests, driving the country’s multifaceted engagement within the region.

4. Brussels concerns for China’s influence and intervention in the CEE region

European anxieties revolve around three main concerns that deserve close examination. First, there is the question of the fragmentation of the European Union. Second, there are concerns about China’s potential leverage over Western Europe, and Brussels in particular, including political and financial decisions that could divert countries from their path towards European integration. Third, and closely related to the second concern, is the fear of falling victim to what is commonly referred to as “debt trap diplomacy”,[38] although this expression has been criticized and debunked.[39],[40]

The first concern is that China is trying to create a cohesive network within the Central and Eastern European region in order to influence the European Union from within. This influence is primarily aimed at promoting policies in line with China’s interests. Beijing uses a combination of hard and soft power instruments to achieve this goal, with foreign direct investment (FDI) being a prominent tool.[41] In particular, as has been shown in Table 1, Chinese FDI is disproportionately concentrated in Western Europe and import/export economic relations follow the same pattern, undermining the notion that CEE markets are dominated by China’s trade interests. Additionally, as Pavlićević notes, Western European CEE economies are so highly integrated that any attempt to sow discord and pivot them significantly towards China is unlikely. Being well aware of this reality, Chinese policymakers are likely to find Brussels more receptive to their goals through engagement with governments in Berlin, London or Paris than in Budapest, Warsaw or Belgrade.[42]

Findings from the 2021 online meeting of the 16 + 1 (formerly 17 + 1) scheme underscore that, while frustration with EU policies may be driving some CEE countries closer to China, the relationship is not unidirectional. Lithuania’s decision to withdraw from the cooperation and reduce the scheme to 16 + 1 following concerns about EU unity is a case in point.[43] Indeed, the expected surge in trade within the 17 + 1 scheme did not materialise, highlighting the nuanced dynamics at play.[44] Additionally, China’s focus on Serbia as the main recipient of its infrastructure projects in the region has also led to rising discontent among several other CEE countries.[45]

The second concern revolves around China’s potential leverage over Western Europe, a fear that is closely linked to China’s economic and political presence in CEE. This concern is particularly pertinent in the context of the five Western Balkan countries, which are among the 16+1 CEE countries but are not yet EU members. The question here is how China’s financial presence could recalibrate the power dynamics in the region so as to undermine EU control and hinder the European integration of these countries. This fear has tangible and significant implications, as highlighted by Zweers et al.[46]

Closely related to this leverage is the third concern, which revolves around the fear that China could exert undue influence over CEE countries through loans and interest rates through opaque debt trap diplomacy. This phenomenon has been repeatedly linked to China’s broader foreign policy efforts,[47] with Chellaney being one of the first to apply the concept to China’s financial underpinning of Belt and Road Initiative projects.[48]

A relevant case in the CEE region that illustrates this concern is the Montenegrin motorway project. This motorway, which is supposed to connect the Serbian border with the Adriatic port of Bar, remains incomplete and has already earned the nickname “the highway from nowhere to nowhere”.[49] The project is mainly financed by loans (85%) and government funds (15%), with the government borrowing heavily from the Chinese Exim Bank. The project’s incompleteness has raised concerns about the country’s rising debt, which now stands at 103% of GDP due to the loans. While the first instalment was successfully repaid in 2021, doubts about the project’s ability to generate the expected revenues remain.[50] The narrative of debt trap diplomacy has been widely invoked in this context, fuelled by concerns that China could gain leverage over Montenegro through its debt, potentially even affecting the strategic port of Bar in the event of a renegotiation.[51]

In a region already grappling with corruption concerns,[52] the Chinese approach to lending for infrastructure projects, reminiscent of its practices in developing countries, could exacerbate economic vulnerabilities. Given the disappointments of the EU’s peripheral and candidate countries, there is a compelling case for the EU to take a more proactive stance on infrastructure projects in these regions, even beyond its borders. This approach would address economic needs while allowing strict financial oversight to be maintained. More importantly, it would also accelerate these countries’ progress towards EU integration.

In spite of these concerns, the Chinese presence should not be viewed solely through a lens of criticism and alarm. Instead, it can serve as a wake-up call, highlighting the urgent need for infrastructure development in the region and its potential impact on the future of these countries if neglected. It might therefore be asked whether the EU should not reconsider its old policy of not providing funding for infrastructure development outside the EU, especially in candidate and potential candidate countries.

In this context, the Global Gateway initiative launched by the European Commission and the High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy on 1 December 2021 is significant. This initiative aims to strengthen global health, education, research systems and infrastructure in line with clean energy, digital transformation, and secure transport links.[53] By mobilising up to €300 billion of investment between 2021 and 2027, the initiative aims to address pressing global challenges while also promoting sustainable and beneficial connections. However, there is a need for the initiative to take on a more concrete dimension,[54] particularly as a response to the ‘wake-up call’ for an EU counterbalancing intervention in the Western Balkans.

5. Conclusion

While the 17+1 mechanism has led to a degree of connectivity between CEE nations and China, these ties predominantly remain on the surface, characterized by disparities across the bloc. Similarly, initial apprehensions regarding China’s endeavour to establish a sphere of influence in Central and Eastern Europe not been substantiated thus far. Not merely being far removed from China geographically nit also firmly anchored within the European Union and closely aligned with to the West, economic and political linkages between China and CEE countries remain shallow to say the least.

The varying degree of effectiveness showcased by the 17+1 mechanism over the decade since its inception may be attributed to misinterpretations or a lack of mutual comprehension, which led to divergent expectations from the outset. Conversely, CEE nations exhibit highly heterogeneous perspectives on collaboration with China. As mentioned previously, the 17+1 participants are characterized by their diversity and the heterogeneous nature of the objectives they pursue. Lithuania’s withdrawal from the platform, driven by a desire to foster closer ties with the European Union and its allies, may potentially signal a similar trajectory for other participants. Such countries might opt to disengage from their collaboration with China or to selectively relinquish specific aspects of it in favour of enhancing relations with Western counterparts. The most plausible course of action could involve CEE nations reducing their participation in the platform and opting for bilateral relations as a means to alleviate external pressures.

It is worth underscoring that China will continue to maintain a substantial presence in Europe and, as the European Union seeks to devise a novel approach towards China, Central and Eastern Europe shall probably assume a pivotal role in this future strategy. Serving as a physical bridge linking Western Europe and Asia, CEE countries shall necessarily remain a pivotal factor in European-China relations.

The trajectory of China–Central and Eastern European cooperation thus hinges upon the capacity of nations to cultivate common ground for collaboration while adeptly navigate the complex terrain of EU dynamics and ever more competition between the United States and China. Future research endeavours are bound to explore the escalating ramifications of U.S.–China competition within the CEE region in more detail, notably concentrating on China’s response to a more adversarial posture adopted by select CEE nations and the EU itself. As the EU introduces novel instruments and initiatives, the landscape of these relationships is poised to undergo a major transformation which, sooner or later, is bound to have a profound influence on the posture CEE nations adopt within the framework of the 17+1 mechanism.

References

-

Julia Melnikova, “China and Europe: What Was It? The Rise and Crumbling of the ‘16+1’ Format,” Valdai Club (blog), accessed September 24, 2023, https://valdaiclub.com/a/highlights/china-and-europe-what-was-it-the-rise-and-crumblin/. ↑

-

China-CEEC, “The Dubrovnik Guidelines for Cooperation between China and Central and Eastern European Countries,” 2019, https://china2ceec.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/2019-Dubrovnik-Guidelines.pdf. ↑

-

Lau Stuart, “Lithuania Pulls out of China’s ’17+1′ Bloc in Eastern Europe,” POLITICO (blog), May 21, 2021, https://www.politico.eu/article/lithuania-pulls-out-china-17-1-bloc-eastern-central-europe-foreign-minister-gabrielius-landsbergis/. ↑

-

David Sacks, “Countries in China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Who’s In And Who’s Out,” Council on Foreign Relations (blog), accessed September 24, 2023, https://www.cfr.org/blog/countries-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative-whos-and-whos-out. ↑

-

Lau Stuart, “China’s New Vassal: Vladimir Putin,” POLITICO (blog), June 6, 2022, https://www.politico.eu/article/china-new-vassal-vladimir-putin/. ↑

-

Lau Stuart, “Down to 14 + 1: Estonia and Latvia Quit China’s Club in Eastern Europe,” POLITICO (blog), August 11, 2022, 14, https://www.politico.eu/article/down-to-14-1-estonia-and-latvia-quit-chinas-club-in-eastern-europe/. ↑

-

Lau Stuart, “China’s Club for Talking to Central Europe Is Dead, Czechs Say,” POLITICO (blog), May 4, 2023, https://www.politico.eu/article/czech-slam-china-xi-jinping-pointless-club-for-central-europe/. ↑

-

Anastas Vangeli, “Global China and Symbolic Power: The Case of 16 + 1 Cooperation,” Journal of Contemporary China 27, no. 113 (September 3, 2018): 674–87, https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2018.1458056. ↑

-

Alfred Gerstl, “Governance Along The New Silk Road In Southeast Asia and Central and Eastern Europe: A Comparison of ASEAN, The EU and 17+1,” Jebat: Malaysian Journal of History, Politics & Strategic Studies 47, no. 1 (2020), http://ejournal.ukm.my/jebat/article/view/39015. ↑

-

Thorsten Benner and Jan Weidenfeld, “Europe, Don’t Let China Divide and Conquer,” POLITICO (blog), March 19, 2018, https://www.politico.eu/article/europe-china-divide-and-conquer/. ↑

-

Weiqing Song and Lilei Song, “Assessing China’s ‘16+1 Cooperation’ with Central and Eastern Europe: A Public Good Perspective,” in The Belt and Road Initiative: An Old Archetype of a New Development Model, ed. Francisco José B. S. Leandro and Paulo Afonso B. Duarte (Singapore: Springer, 2020), 411–31, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-2564-3_17. ↑

-

Lilei Song and Dragan Pavlićević, “China’s Multilayered Multilateralism: A Case Study of China and Central and Eastern Europe Cooperation Framework,” Chinese Political Science Review 4, no. 3 (September 1, 2019): 277–302, https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-019-00127-z. ↑

-

Lauren Speranza and Candace Huntington, “China’s Failures in CEE Open the Door for the U.S.,” CEPA (blog), April 5, 2021, https://cepa.org/article/chinas-failures-in-cee-open-the-door-for-the-u-s/. ↑

-

Gerstl, “Governance Along The New Silk Road In Southeast Asia and Central and Eastern Europe.” ↑

-

Song and Pavlićević, “China’s Multilayered Multilateralism.” ↑

-

Bruno Macaes, “How Europe Learned to Fear China,” POLITICO (blog), April 9, 2019, https://www.politico.eu/blogs/the-coming-wars/2019/04/how-europe-learned-to-fear-china/. ↑

-

Committee of Foreign Affairs, “On a New EU-China Strategy” (European Parliament, 2021), https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-9-2021-0252_EN.html. ↑

-

Edward Lucas, “Chinese Influence in Central and Eastern Europe,” CEPA (blog), August 2, 2022, https://cepa.org/comprehensive-reports/chinese-influence-in-central-and-eastern-europe/. ↑

-

Andreea Brinza, “China Keeps Betting on the Wrong Politicians,” Foreign Policy (blog), March 10, 2023, https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/03/10/china-influence-diplomacy-central-eastern-europe-czech-republic/. ↑

-

Laurie Chen and Yew Lun Tian, “China’s Xi Warns against Decoupling, Lauds Belt and Road at Forum,” Reuters, October 18, 2023, sec. World, https://www.reuters.com/world/chinas-xi-lauds-belt-road-smaller-greener-summit-2023-10-18/. ↑

-

Christoph Nedopil Wang, “China Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Investment Report 2023 H1 – Green Finance & Development Center” (Green Finance & Development Center, August 1, 2023), https://greenfdc.org/china-belt-and-road-initiative-bri-investment-report-2023-h1/. ↑

-

PRC Government, “Vision and Actions on Jointly Building the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road,” Belt and Road Portal, March 30, 2015, https://eng.yidaiyilu.gov.cn/p/1084.html. ↑

-

Xinhua Silk Road Information Service, “What Are the Six Economic Corridors of BRI?,” Xinhua News, March 16, 2020, https://en.imsilkroad.com/p/311988.html. ↑

-

Polly Bindman, “Weekly Data: China Seeks to Extend Its Critical Minerals Dominance with Overseas Investment Surge,” Energy Monitor (blog), August 21, 2023, https://www.energymonitor.ai/sectors/industry/weekly-data-china-seeks-to-extend-its-critical-minerals-dominance-with-overseas-investment-surge/. ↑

-

Christine Wong, “The Fiscal Stimulus Programme and Public Governance Issues in China,” OECD Journal on Budgeting 11, no. 3 (October 24, 2011): 1–22, https://doi.org/10.1787/budget-11-5kg3nhljqrjl. ↑

-

Gideon Rachman, “Russia and China’s Plans for a New World Order,” Financial Times, January 23, 2022, sec. The Big Read, https://www.ft.com/content/d307ab6e-57b3-4007-9188-ec9717c60023. ↑

-

The Economist, “Faced with an Overseas Debt Crisis, Will China Change Its Ways?,” accessed September 25, 2023, https://www.economist.com/china/2022/08/24/faced-with-an-overseas-debt-crisis-will-china-change-its-ways. ↑

-

Alan Rappeport, “Pressure Mounts on China to Offer Debt Relief to Poor Countries Facing Default,” The New York Times, April 14, 2023, sec. Business, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/14/business/economy/china-debt-relief.html. ↑

-

Agnes Szunomar, “China in Europe: All for One and One for All?,” May 29, 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2020/05/china-in-europe-all-for-one-and-one-for-all/. ↑

-

David Pierson and Lynsey Chutel, “China Tries to Increase Its Clout in Africa Amid Rivalry With the U.S.,” The New York Times, August 23, 2023, sec. World, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/23/world/asia/china-africa-brics-us.html. ↑

-

James McBride, Noah Berman, and Andrew Chatzky, “China’s Massive Belt and Road Initiative,” Council on Foreign Relations, February 2, 2023, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/chinas-massive-belt-and-road-initiative. ↑

-

Richard Q. Turcsányi, “China and the Frustrated Region: Central and Eastern Europe’s Repeating Troubles with Great Powers,” China Report 56, no. 1 (February 1, 2020): 60–77, https://doi.org/10.1177/0009445519895626. ↑

-

Agatha Kratz et al., “Chinese FDI in Europe: 2021 Update,” METRICS (blog), April 27, 2022, https://merics.org/en/report/chinese-fdi-europe-2021-update. ↑

-

Heather A. Conley et al., “China’s ‘Hub-and-Spoke’ Strategy in the Balkans” (CSIS, April 2020), https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/200427_ChinaStrategy.pdf. ↑

-

Nikola Đorđević, “Montenegro Narrowly Avoids Chinese Dept Trap, for Now,” Emerging Europe (blog), August 9, 2021, https://emerging-europe.com/news/montenegro-narrowly-avoids-chinese-debt-trap-for-now/. ↑

-

Vladimir Shopov, “Decade of Patience: How China Became a Power in the Western Balkans,” Policy Brief (ECFR, February 2021), https://ecfr.eu/wp-content/uploads/Decade-of-patience-How-China-became-a-power-in-the-Western-Balkans.pdf. ↑

-

Wouter Zweers et al., “China and the EU in the Western Balkans: A Zero-Sum Game?” (Clingendael, August 2020), https://www.clingendael.org/sites/default/files/2020-08/china-and-the-eu-in-the-western-balkans.pdf. ↑

-

Brahma Chellaney, “China’s Debt-Trap Diplomacy,” Project Syndicate (blog), January 23, 2017, https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/china-one-belt-one-road-loans-debt-by-brahma-chellaney-2017-01. ↑

-

Michal Himmer and Zdeněk Rod, “Chinese Debt Trap Diplomacy: Reality or Myth?,” Journal of the Indian Ocean Region 18, no. 3 (September 2, 2022): 250–72, https://doi.org/10.1080/19480881.2023.2195280. ↑

-

Deborah Brautigam and Meg Rithmire, “The Chinese ‘Debt Trap’ Is a Myth,” The Atlantic (blog), February 6, 2021, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2021/02/china-debt-trap-diplomacy/617953/. ↑

-

Turcsányi, “China and the Frustrated Region.” ↑

-

Dragan Pavlićević, “China in Central and Eastern Europe: 4 Myths,” January 16, 2016, https://thediplomat.com/2016/06/china-in-central-and-eastern-europe-4-myths/. ↑

-

Stuart, “Lithuania Pulls out of China’s ’17+1′ Bloc in Eastern Europe.” ↑

-

Yu Jie, Ivana Karásková, and Edward Lucas, “17+1: China’s Foreign Policy in Central Europe,” London School of Economics and Political Science, May 28, 2021, https://www.lse.ac.uk/ideas/events/2021/05/chinas-foreign-policy-in-central-europe/chinas-foreign-policy-in-central-europe.aspx. ↑

-

Conley et al., “China’s ‘Hub-and-Spoke’ Strategy in the Balkans.” ↑

-

Zweers et al., “China and the EU in the Western Balkans: A Zero-Sum Game?” ↑

-

Shopov, “Decade of Patience: How China Became a Power in the Western Balkans.” ↑

-

Chellaney, “China’s Debt-Trap Diplomacy.” ↑

-

Andrew Higgins, “A Pricey Drive Down Montenegro’s Highway ‘From Nowhere to Nowhere,’” The New York Times, August 14, 2021, sec. World, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/14/world/europe/montenegro-highway-china.html. ↑

-

Reid Standish and Amos Chapple, “A Journey Along Montenegro’s $1 Billion Chinese-Built Highway,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 19:03:55Z, sec. Montenegro, https://www.rferl.org/a/montenegro-billion-dollar-chinese-highway/32217524.html. ↑

-

Samir Kajosevic, “Montenegro Authorities Exaggerated Cost of Highway, Surveys Show,” Balkan Insight (blog), November 16, 2021, https://balkaninsight.com/2021/11/16/montenegro-authorities-exaggerated-cost-of-highway-surveys-show/. ↑

-

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, “Corruption in the Western Balkans: Bribery as Experienced by the Population” (UNODC, 2011), https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/statistics/corruption/Western_balkans_corruption_report_2011_web.pdf. ↑

-

Léo Portal, “The Global Gateway (Part 1): A European Response to the Belt and Road,” Blue Europe (blog), June 30, 2023, https://www.blue-europe.eu/analysis-en/full-reports/the-global-gateway-part-1-a-european-response-to-the-belt-and-road/. ↑

-

Léo Portal, “The Global Gateway (Part 2): Is It Failing Its Objectives?,” Blue Europe (blog), July 31, 2023, https://www.blue-europe.eu/analysis-en/full-reports/the-global-gateway-part-2-is-it-failing-its-objectives/. ↑