1. Introduction

Brain drain – the emigration of skilled professionals to pursue opportunities abroad in another country – has emerged as a significant challenge for Central-Eastern European countries in recent decades,[1]–[2] and Slovakia is not the exception to this phenomenon. Following its transition from a centrally planned economy to a market economy and subsequent accession to the European Union in 2004, Slovakia witnessed an unprecedented wave of emigration, particularly among young, educated professionals. This phenomenon created labour shortages in critical sectors, notably healthcare, education, and information technology, while exacerbating regional disparities within the country.

The economic toll of this brain drain is immense. Estimates suggest that the loss of a single university-educated individual could cost the country €2.8 million over their lifetime.[3] For a nation striving to transition from a recently developed production-based economy to one focused on innovation, retaining and attracting talent is not just important – it is essential. The underlying causes of Slovakia’s brain drain are multifaceted and addressing this challenge has become a critical focus for policymakers, government bodies, and civil society alike.[4]

In the next sections, we will examine the data to understand the proportion of the phenomenon, analysing the government and private sector’s efforts to address the challenge, and exploring relevant case studies.

2. Quantifying Slovakia’s “Diaspora”

Slovakia, an EU member since 2004, shares borders with Poland, Ukraine, Hungary, Austria, and the Czech Republic. Since Slovakia’s accession to the European Union, the mobility patterns of Slovak citizens have shifted considerably. Since this analysis refers to the phenomenon of brain drain, we will focus mostly on the movement of Slovak students.

In 2016, approximately 17% of Slovak students were enrolled in universities abroad, against an EU average of 4%.[5] Slovak students at Czech universities typically come from highly educated, middle-to-upper-class families.[6] They benefit from better social and financial conditions compared to their Czech and Slovak peers, including higher monthly incomes and less need for work during studies. However, Slovak doctoral students often express reluctance to return to Slovakia or remain in the Czech Republic after completing their education, but would rather move to Western and Northen European countries. In total, around 60% of young Slovaks considers moving abroad.[7]

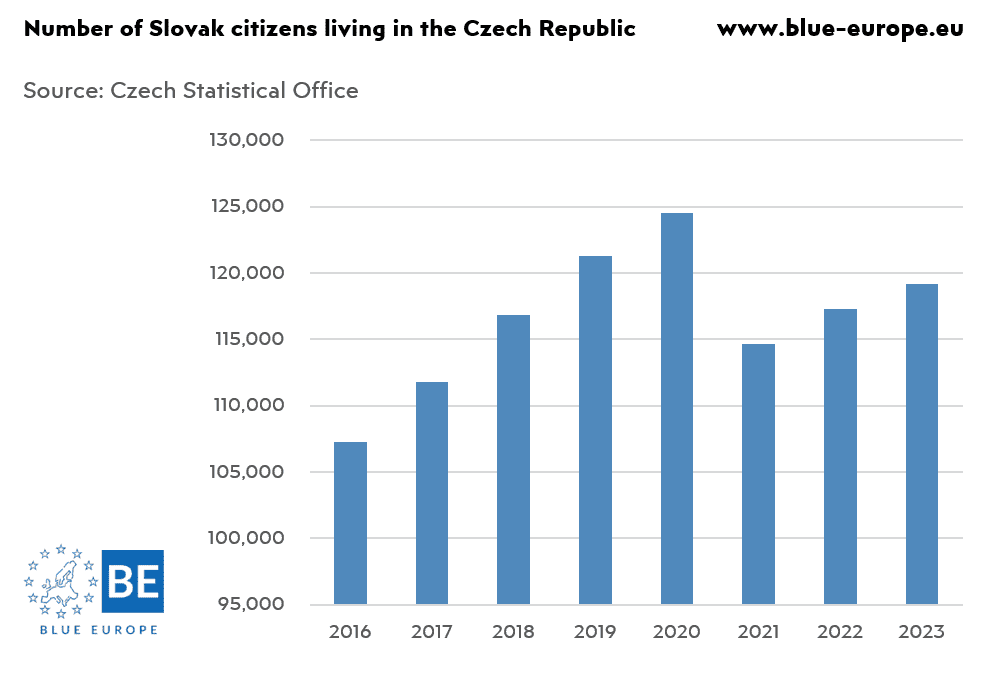

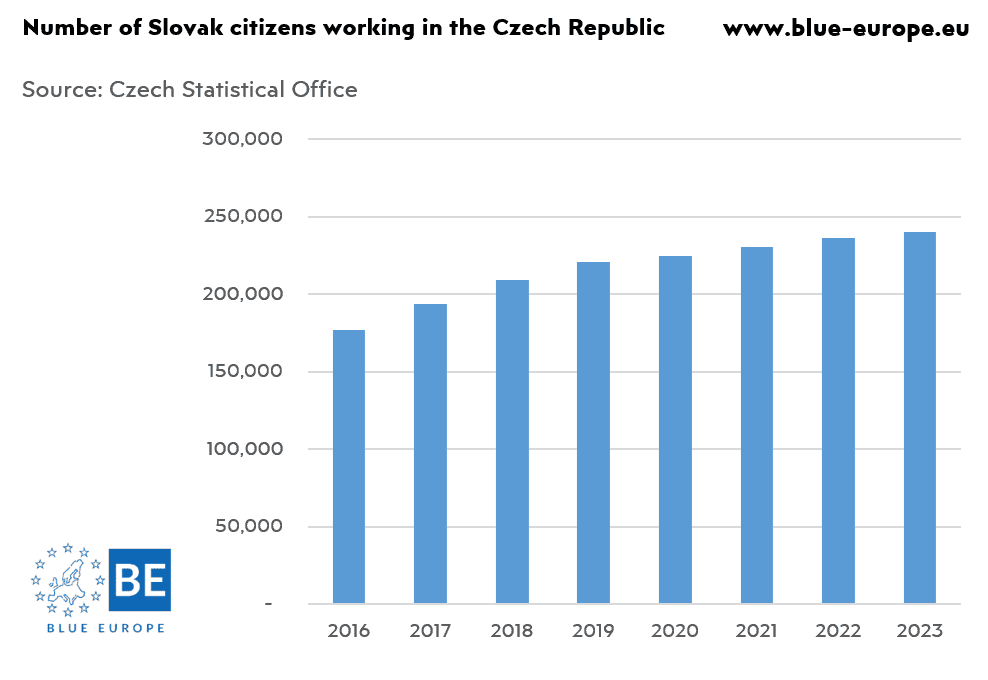

In the chart below we can see that the number of Slovaks living in the Czech Republic has diminished considerably during the pandemic, probably signalling a return home enabled by telecommuting/smart working and distance learning. Nevertheless, since 2021 Slovak citizens have begun to relocate again in Czechia.

The number of Slovaks working in the Czech Republic has also grown gradually – surpassing 240,000 in 2023, a figure that has doubled over the past decade. Nearly 10% of the population lives overseas – twice the rate of other OECD nations. This significant presence in the Czech workforce suggests that for many, the move is not just a temporary pursuit of better educational opportunities nearby, but a deliberate decision to establish a career and build a life away from Slovakia.

According to recent census, close to 300,000 individuals recorded in Slovakia’s recent census may not actually reside in the country. This discrepancy arises from common practices among Slovaks, such as failing to report their expatriation, maintaining an official address in Slovakia, or commuting weekly to neighbouring countries like Austria or Hungary for work.

This lack of accurate data complicates efforts to measure the full impact of brain drain/emigration and assess whether Slovakia is experiencing a permanent loss of its most talented individuals. Without clear information on how many Slovaks are living abroad and the duration of their stays, understanding the true extent of the problem remains a challenge for policymakers.

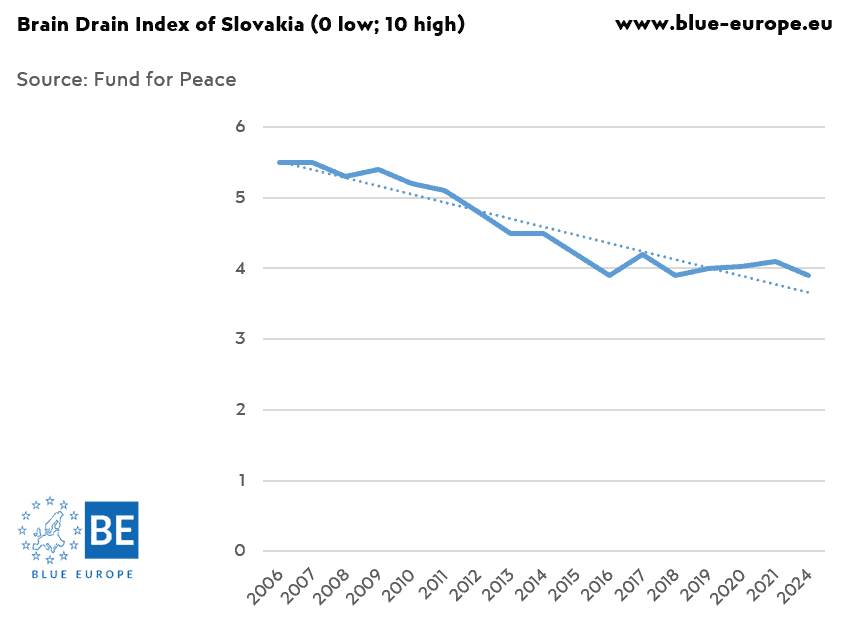

The Fund for Peace’s Human flight and brain drain indicator considers the economic impact of human displacement (for economic or political reasons) and the consequences this may have on a country’s development. This index is available from 2006 and, as shown in the chart below, Slovakia’s descending trend signals that the increase in the past 4-5 years is conjunctural. Hence, we can conclude that while the phenomena remains troubling, the policies implemented and the gradual development of the Slovak economy are contributing to a gradual betterment of the situation.

3. Motives for relocating abroad

Youth emigration from Slovakia is marked by a mix of temporary and long-term migrations, with many young Slovaks considering leaving, though only a minority plan to stay abroad permanently. Studies indicate that a large proportion of Slovaks studying or working abroad are open to returning within a few years.[8] However, the ambiguous nature of this migration – neither entirely permanent nor temporary – has led to limited structural reforms, as policymakers often hope returning migrants will replenish human capital without significant investment.

While young Slovaks emigrate to various countries across Europe and beyond, including Austria, Germany, France, the UK, and even the US, the Czech Republic stands out as the primary destination. Due to its geographical and cultural proximity, a shared language, and the opportunity to study for free at well-regarded universities, it has become the natural choice for many Slovak students. In fact, around 70% of Slovaks studying abroad choose to do so in the Czech Republic, with Prague and Brno being the most popular locations.[9]

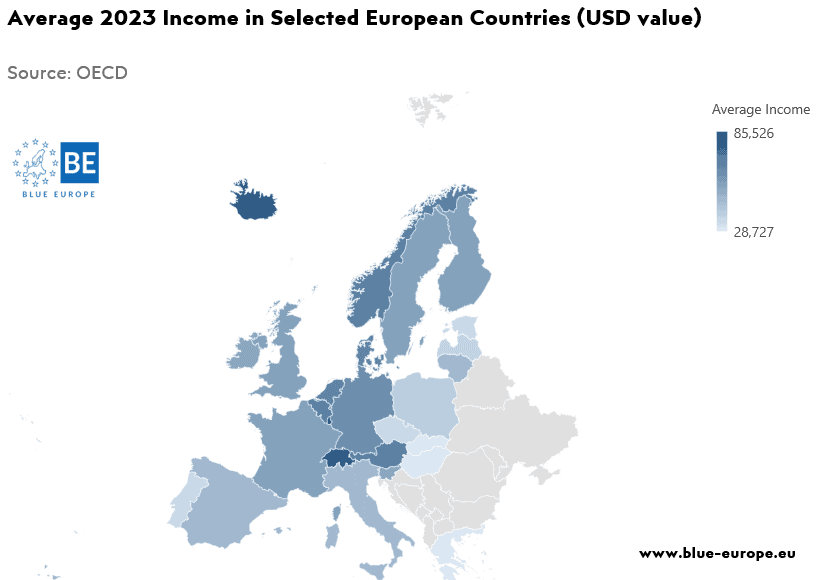

Economic considerations have long been the key motivator for Slovaks, especially young students, migrating westward, with many skilled workers choosing Austria or Germany for higher-paying jobs. Slovakia’s persistent socio-economic challenges, particularly its regional inequalities, contrast sharply with the performance of its neighbours. Even for those who find work in Slovakia, the advantages of living abroad are hard to ignore. Slovakia has a relatively low average income and while prices in Slovakia are around 10% lower than the EU average, the cost of living remains high in comparison to wages. Just a few hours away, the Czech Republic offers higher purchasing power, better wages, and a more favourable employment market, making it an increasingly attractive destination for Slovaks seeking better living standards.

The following chart illustrates the wage disparities that drive emigration. As of 2023, Slovakia’s average annual income was $29,838.00, less than half of Austria’s $67,431.00 or Germany’s $62,473.00. This underscores how higher wages in neighbouring countries incentivize Slovak professionals to emigrate, particularly in fields where demand is high, such as IT and engineering.

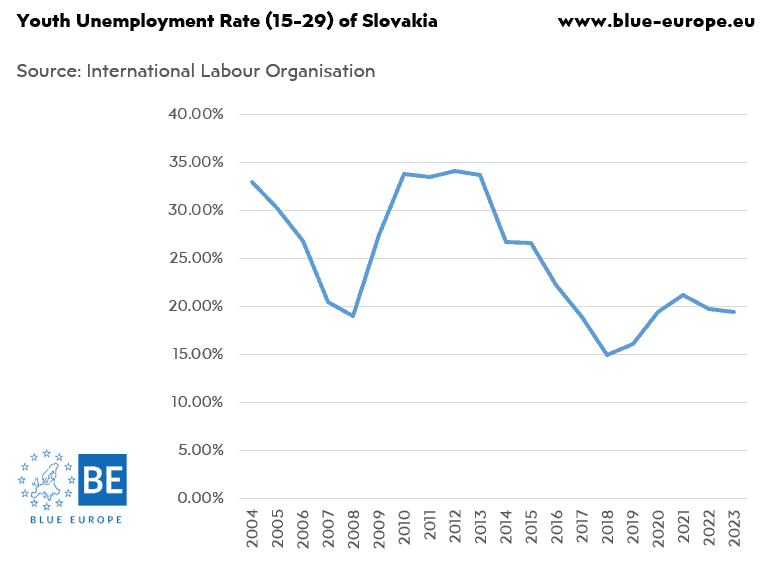

A major indicator linked to brain drain phenomena is the unemployment rate of young individuals. According to the World Bank, Slovakia has a youth unemployment rate (15-24) of 19.4%, with rates even higher in the economically weaker eastern regions, which account for a significant proportion of young emigrants. In contrast, the Czech Republic, along with Poland, has enjoyed one of the lowest unemployment rate in the EU for several years (8.3% and 11.6% respectively), and businesses there have increasingly relied on foreign workers, including Slovaks. As shown in the chart below, Slovakia’s youth unemployment rate follows economic conjunctures and increases in correspondence of the 2008 crisis and the 2020 pandemic.

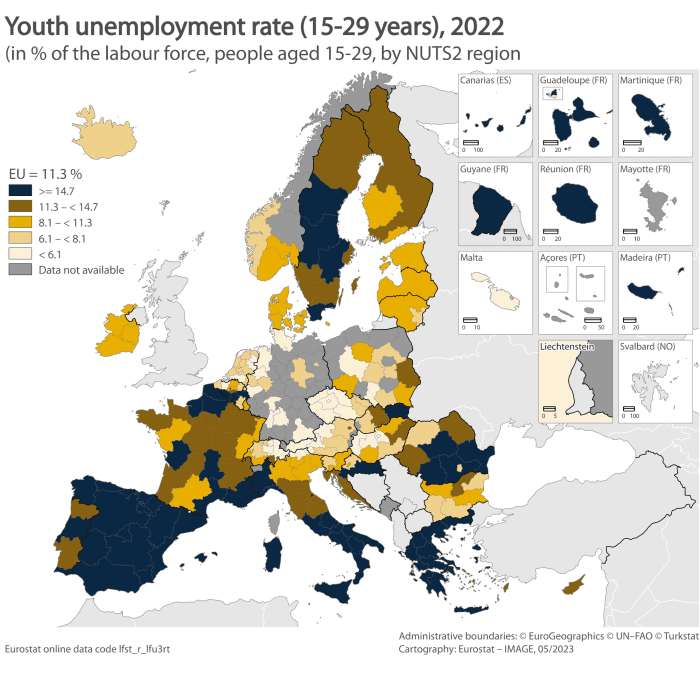

Regional inequalities within Slovakia exacerbate the problem. While Bratislava has benefited from foreign direct investment and EU funds, regions like Prešov and Košice face higher unemployment and limited job prospects, driving internal and external migration. This regional disparity further centralizes talent in the capital, leaving other regions struggling with depopulation and economic stagnation. The map below exemplifies this situation, where Slovak youth unemployment (15-29) decreases going westward.

Another aspect to take into consideration is the quality of institutions and the state of democracy. Despite allegations of significant talent loss and purported brain drain correlated to the leadership of populist figures like Robert Fico,[10] Slovakia is demonstrating a long-term sign of improvement. While some data highlights concern about the number of Slovaks studying or working abroad, the broader picture suggests a more complex reality, with many citizens choosing to remain or return, contributing to the country’s development. Moreover, several indexes developed by independent institutions depict a different scenario for Slovakia’s civil society. Examples include Varieties of Democracy’s indexes for Political corruption, Government accountability, Liberal democracy, Electoral democracy and Freedom of expression; or Freedom House’s Civil liberties and Political rights indexes. In the chart below, the Rule of law index of the World Bank is showcased.

Misrepresenting the brain drain phenomenon risks perpetuating a harmful cycle by fuelling perceptions of long-term stagnation or decline, which could inadvertently exacerbate the very problem it seeks to highlight. Media coverage plays a crucial role in shaping public perception and influencing individual decisions, particularly among young individuals. A focus on anecdotal accounts of emigration or sensationalized narratives without a nuanced interpretation of data risks creating an exaggerated sense of crisis, reinforcing the dichotomy of skilled leaving versus unskilled staying.[11] This, in turn, may discourage potential returnees or prompt others to consider leaving, further amplifying the challenges Slovakia faces.

4. Initiatives to Address Brain Drain

Despite the significant economic consequences of the outflow of young talents, the Slovak governments have been slow to address the issue. However, recent initiatives have emerged with the goal of encouraging Slovaks to return home, both from public institutions and the private sector.[12] Initiatives and reforms can be grouped into three main categories: 1) education reforms; 2) regional and economic development; and 3) return programs.

Once one of Europe’s youngest countries, Slovakia now faces rapid aging, with projections suggesting a loss of one million individuals of working age by 2060.[13] This shift is compounded by a low fertility rate, a significant portion of births occurring abroad, and an uncertain population count due to incomplete emigration data.

One of the most notable initiatives implemented by the Slovak government was the programme “Návrat Domov” (Home-coming),[14] which allocated €3 million to attract young talents back between 2015 and 2018. More recently, initiatives under the Recovery and Resilience Plan have expanded, with €106 million designated for talent retention and attraction, including scholarships for high-performing domestic and foreign students and strategies to maintain connections with the diaspora. Additionally, the government aims to internationalize higher education and enhance opportunities for both Slovak and foreign students to encourage cross-border academic mobility. Despite these steps, systemic issues such as insufficient R&D funding and limited career opportunities compared to neighbouring countries continue to deter many from returning.

Efforts to reverse the talent outflow are aiming to bring back at least 40,000 Slovaks living abroad. Slovakia’s newly established research and innovation authority, VAIA, has prioritized this issue. The Research and Innovation Authority (VAIA) is an organization within the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister of Slovakia, established in 2021. As the implementer of Component 9 of the Recovery and Resilience Plan, VAIA is responsible for reforming the management, evaluation, and support of science, research, and innovation in Slovakia. VAIA’s efforts are also aligned with the National Strategy for Research, Development, and Innovation 2030, which sets the main objectives and priorities for Slovakia in these fields.

Nevertheless, to meet VAIA’s goal of 40,000 returnees, Slovakia must provide practical incentives to encourage brain return. Proposals include tax breaks for entrepreneurs, low-interest mortgages for first-time homebuyers, and subsidies for childcare – measures that would address both financial and social challenges. Drawing inspiration from Hungary’s policies, Slovakia might also consider income-tax exemptions for larger families to counteract its demographic decline, as the country has experienced more deaths than births since 2021.

In fact, real-world incentives are key to encourage relocation.[15] Particularly, Slovakia should concentrate on structural reforms that will benefit the overall economy in the long term, especially targeting innovative sectors that offer better opportunities for young talents. For instance, infrastructure investments, supported by EU structural funds, have modernized transportation, broadband connectivity, and public facilities in regions like Prešov and Košice, making them more attractive for businesses and residents. Additionally, to decentralize economic activity from Bratislava, technology parks and innovation hubs, such as the IT cluster in Košice, are creating high-quality job opportunities in other regions. Additionally, the Slovak Professionals Abroad Program serves as a platform for Slovaks abroad to access job opportunities, participate in networking events, and receive relocation support, while also involving returnees in knowledge-sharing initiatives to address gaps in critical sectors.

One notable example from the private sector is TITANS,[16] a Slovak platform for companies to hire IT freelancers. Through workshops and collaborations with academic institutions, TITANS aims to demonstrate that high-quality IT projects and rewarding career opportunities are already available within Slovakia, also through remote working

5. Conclusion

Addressing brain drain requires a holistic approach that tackles its root causes while creating a conducive environment for talent retention and repatriation. For Slovakia, this involves addressing wage disparities, improving working conditions in critical sectors like healthcare, and fostering regional development to reduce internal inequalities. Investments in education and innovation are crucial. By enhancing its higher education system and supporting research and entrepreneurship, Slovakia can create opportunities that retain its brightest minds.

Regional cooperation within the EU offers additional opportunities. Slovakia can collaborate with neighbouring countries to develop joint initiatives that address common challenges. Ultimately, the return of skilled individuals – also through new telecommuting/distance learning possibilities – could have a transformative effect. Beyond economic contributions, a generation of young Slovaks with global exposure and expertise could re-establish roots in their homeland, driving growth.

References

- Daniela Bobeva, ‘Brain Drain from Central and Eastern Europe’, MPRA Paper, MPRA Paper, 1997, https://ideas.repec.org//p/pra/mprapa/61505.html. ↑

- Solon Ardittis, ‘The New Brain Drain from Eastern to Western Europe’, The International Spectator, 1 January 1992, https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729208457963. ↑

- Zuzana Palovic, ‘Homeward Bound? Slovakia’s Battle to Reverse Its Brain Drain’, CEPA, 7 December 2023, https://cepa.org/article/homeward-bound-slovakias-battle-to-reverse-its-brain-drain/. ↑

- Palovic. ↑

- Jules Eisenchteter, ‘Slovakia Faces Tough Choices as Youth Continues to Leave’, Balkan Insight (blog), 17 November 2022, https://balkaninsight.com/2022/11/17/slovakia-faces-tough-choices-as-youth-continues-to-leave/. ↑

- Jakub Fischer and Hana Lipovská, ‘BRAIN DRAIN – BRAIN GAIN: SLOVAK STUDENTS AT CZECH UNIVERSITIES’, Journal on Efficiency and Responsibility in Education and Science 8, no. 3 (24 November 2015): 54–59, https://doi.org/10.7160/eriesj.2015.080301. ↑

- Marián Koreň, ‘Half of Young, Educated Slovaks Look to Escape Country’, Euractiv, 9 July 2021, https://www.euractiv.com/section/politics/short_news/half-of-young-educated-slovaks-look-to-escape-country/. ↑

- Eisenchteter, ‘Slovakia Faces Tough Choices as Youth Continues to Leave’. ↑

- Martina Chrancokova, Gabriel Weibl, and Dusana Dokupilova, ‘The Brain Drain of People from Slovakia’, Economic and Social Development: Book of Proceedings, 2020, 320–29. ↑

- Ladka Bauerova, ‘Slovakia’s Brain Drain “Picks up Pace” under Populist Leader Robert Fico’, The Observer, 30 March 2024, sec. World news, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/mar/30/slovakia-brain-drain-populist-leader-robert-fico. ↑

- Blerina Gjerazi, ‘Media Influence on Brain Drain Perceptions: An In-Depth Examination of Framing Dynamics’, European Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 4, no. 1 (29 February 2024): 59–66, https://doi.org/10.24018/ejsocial.2024.4.1.523. ↑

- N.D., ‘Turning Slovakia’s Brain Drain into Brain Gain’, The Slovak Spectator, 6 April 2021, https://spectator.sme.sk/opinion/c/turning-slovakias-brain-drain-into-brain-gain. ↑

- Tim Judah, ‘Slovakia: Getting Old Fast’, Balkan Insight (blog), 27 January 2022, https://balkaninsight.com/2022/01/27/slovakia-shows-signs-of-ageing/. ↑

- Fischer and Lipovská, ‘BRAIN DRAIN – BRAIN GAIN’. ↑

- Karin Mayr and Giovanni Peri, ‘Brain Drain and Brain Return: Theory and Application to Eastern-Western Europe’, The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy 9, no. 1 (10 November 2009), https://doi.org/10.2202/1935-1682.2271. ↑

- TITANS, ‘IT Projects at TITANS Motivate Students’, TITANS.SK (blog), 15 January 2024, https://www.titans.sk/en/blog/it-projects-at-titans-convince-students-to-stay-in-slovakia. ↑