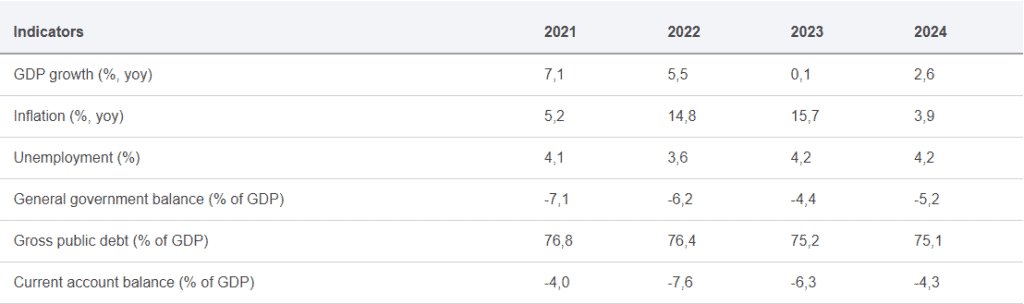

Comparing the second quarter of 2022 with the previous quarter – according to the European Commission – , Hungary’s gross domestic product increased by 1.1%. However, consumer confidence indices have deteriorated and monthly data point to a decline in consumption, housing transactions, construction activity and loans. Higher inflation and energy prices and tighter financing conditions are expected to dampen economic activity in the coming quarters, with real GDP growth slowing from 5.5% in 2022 to 0.1% in 2023 and then recovering to 2.6% in 2024. As household income is eroded by high inflation, consumption is expected to fall in 2023. However, administrative controls on household energy prices and mortgage rates continue to insulate people from rising energy prices and financing costs. As a result of tighter financing conditions and a worsening economic outlook, investment is expected to fall next year. In addition, business investment in energy efficiency will be supported by the government. In addition to the expected cooling of the housing market, fiscal consolidation efforts will limit the volume of public investment from its previously high levels.

Although supply chain problems have eased somewhat, weaker external demand is expected to limit export growth. Between 2021 and 2023, rising energy prices are expected to increase Hungary’s net energy imports by almost 5 % of GDP. Imports of non-energy goods are expected to remain subdued, in line with the decline in final demand. As a result, the current account deficit is projected to widen, peaking at 7.6% of GDP in 2022, before declining steadily to 4.3% in 2024.

Very good looking public finances, but with a considerable inflation

Despite measures such as retail price controls implemented, the war in Ukraine created an energy crisis, and food and electricity costs in Hungary jumped around 50 percent in December compared to the previous year, according to figures from the government. December’s inflation rate was the highest in the European Union at 24.5% year-over-year. The average for the bloc is 10.4 percent. Economists attribute a portion of the blame on a weak forint, the elimination of price ceilings, and a retail tax.

According to them, the price restrictions had a distorting impact, resulting to shortages of fuel and basics such as sugar as importers and retailers refused to sell below cost, as well as price increases for non-capped products as stores sought to compensate for the price cap on other goods. The government was compelled to remove the fuel cap last month when supplies dwindled precipitating frantic purchasing. Lajos Torok, chief analyst at Budapest brokerage Equilor, foresaw a deterioration in the situation.“Household expenses rise so domestic consumption will fall, higher financing costs will delay corporate investments, state investments will be cut back” all but erasing growth, he said.

The government this month launched an advertising campaign claiming a majority of Hungarians opposed the EU’s Russia sanctions, which Orbán has blamed for the country’s economic ills. “This bloody sanctions regime drives inflation skyward,” Orbán told state broadcaster MR1 earlier this month. “If sanctions were to end, energy prices would drop immediately, along with general prices, meaning inflation would halve.” .

“The government has not found the keys,” Hungary’s central bank governor György Matolcsy told a parliamentary committee in December. “We cannot overcome this energy price explosion and inflation crisis in old ways.” “Communism already showed price caps don’t work,” said Matolcsy, who Orbán once described as his “right hand” on economic planning. “That system collapsed. Let’s not return to [it] with such techniques.” Orbán remains defiant, telling MR1 earlier this month that Hungary’s foreign exchange reserves were near a high after recent borrowing, meaning the country was solvent.

Yet, thanks to the close tracking between Hungarian florint value on international markets and inflation, Hungary’s debt fell from 78.6 per cent of gross domestic product at the end of 2021 to 75.3 per cent at the close of last year, below the EU average of 85.1 per cent, according to EU data. In 2022, its budget deficit reached 5.3 per cent of GDP, roughly double the EU’s 2.7 per cent average. This is a very rare situation in Europe, which could repeat over the next 3 years. If the Orban government sets his cards rights, he could even lower it below 65% by the end of his term. This doesn’t mean, however, that the situation for everyday Hungarians will improve (but it definitively have some major impact).

Hungarian Energy Production, the core problem of any economic improvement

The baseline projection for next year is subject to numerous downside risks. As Hungary has limited near-term options to replace Russian oil and gas imports, energy supply disruptions could have a significant impact on the economy. Moreover, high energy prices could threaten the medium-term investment plans of Hungary’s energy-intensive manufacturing sector. Finally, persistently high inflation or deteriorating financial conditions may require a more restrictive policy stance. The EU Commission may reassess the licence for the construction of two new units at the Paks power plant, as Hungary is considering extending the life of the existing units beyond 2037, reversing a previous commitment.

In 2014, Hungary commissioned Russian state-owned energy conglomerate Rosatom to build two 1,200MW reactors at Paks, next to the country’s only nuclear power plant, at a total cost of €12.5bn, financed by a €10bn Russian loan. In 2017, the European Commission approved the project, stating that the financing of the initiative did not involve state aid. However, “it has accepted this financing under EU state aid standards on the basis of commitments made by Hungary”, one of which was to remove existing obstacles according to the original timetable. The existing reactors were expected to be shut down between 2032 and 2037. According to local media, Hungary now risks losing its EU licence if it agrees to extend the life of the existing nuclear reactors. There are four 500 MW units at the Paks nuclear power plant, which supplies half of Hungary’s electricity production and more than a third of its electricity consumption.

Following the European Commission’s approval, Hungarian regulators issued a basic licence in 2017 and preparatory groundwork began in 2021, although the National Atomic Energy Office (OAH) had not yet issued a final licence. The OAH cited safety concerns and only gave the project the green light in August 2022. According to the original schedule, the new units were to be commissioned in 2025 or 2026.

As the largest investment in Hungary’s history has been delayed by at least 6-7 years, the Hungarian Parliament passed a resolution in December asking the government to consider extending the decommissioning dates of existing units by up to 20 years from the current schedule. The action indicated that the government did not rule out the possibility of further delays in the construction of the new units. The European Parliament’s decision came just days after the ECJ rejected an appeal by Austria against the European Commission’s approval of investment aid for the upgrade, ruling that the financing by Russian loans did not breach EU rules.

Austria has objected to the extension in general, saying there is no guarantee that Hungary will actually close Paks I, adding that Hungary will have a strong position in the region with both the existing and new units in operation. The Hungarian government has warned that if the existing units are shut down between 2032 and 2037 without the addition of new nuclear reactors, Hungary’s electricity supply will be at risk.

A Defense Industry Commitment, but at what price?

However, the Hungarian government will score some successes in 2023, mostly around the completion of the long overdue military modernisation. Speaking at the Global Special Operations Forces (GSOF) Europe conference in Budapest in October 2022, the Minister of Technology and Industry said that the Hungarian government aims to make the Hungarian military sector a regional leader by 2030.

László Palkovics noted that it is a national and economic goal for Hungary to become the leading manufacturing and research base in Central Europe for the defence industry. He recalled that the Hungarian defence sector has been reorganised as a result of the Zrnyi 2026 military and armed forces development programme.

In Hungary, defence spending now accounts for 1.2% of GDP. He noted that the Hungarian economy is healthy, with 70 per cent of its output coming from high-tech industries, which can be expanded, and that the country already has an excellent infrastructure. Its location is logistically favourable, and its involvement in NATO and the EU is beneficial.

The government’s goal is to increase the size of the defence industry to HUF 500 billion by 2030. Increased self-sufficiency is necessary for the defence sector to provide services and products to the Hungarian military, according to the minister. It is also crucial that the Hungarian defence industry succeeds in foreign markets and participates in international supply chains with competitive products.

László Palkovics suggested that in order to achieve these goals and ensure economic sustainability, research and development (R&D) capacities must be increased and R&D investment in the defence industry must reach 5 percent of Hungary’s total R&D expenditure. He noted that NATO has identified eight critical issues for the next two decades. Hypersonic capabilities research, data-driven research, artificial intelligence (AI) research, quantum technology, space research, biotechnology, new materials and manufacturing technology research.

He also affirmed that the sectoral strategy will contribute to Hungary’s success. He recalled that the Defence Innovation Research Institute (VIKI) has its headquarters in Budapest and other locations in Szeged and Zalaegerszeg. He listed nuclear, biological and chemical research, telecommunications, artificial intelligence, drones, drone components and GPS as the main areas of research. The dual application of inventions is advantageous, he said, because product sales do not depend solely on the defence industry.

To achieve these goals, the Minister stressed the need to build production capacity and a business model, and to forge technical alliances. He cited the recently completed new Airbus plant in Gyula and the Rheinmetall cooperation as examples that have also contributed to the region’s economic growth. alliances with Austrian, German, French and Turkish companies.

After decades of downsizing and neglect of the defence sector, in the mid-2010s the Hungarian government committed to implementing a comprehensive force development programme to modernise the Hungarian Defence Forces. In 2016, the Hungarian government unveiled the Zrnyi 2026 Defence and Force Development Programme, promising to complete the long-awaited and much-needed modernisation and reform of the HDF within the next decade. The primary goal of the Force Development Programme is to procure NATO-compatible equipment, ranging from personal equipment to combat equipment, produced by the European and Hungarian defence industries. Although the Zrnyi 2026 programme is only halfway through, Hungary’s defence capabilities have grown significantly, which is crucial not only for self-defence and deterrence, but also for the country to remain an influential contributor to regional, European and transatlantic security efforts in challenging times.

The Defence Minister also outlined the future development of the Hungarian military. With the advent of digital technology, the world has undergone profound changes, he emphasised. In recent decades, the military industry has been at the forefront of innovation, and its achievements, such as GPS and the Internet, have found their way into the civilian sector. Today, however, it is not only military research institutes that are producing new technologies, but also start-ups, thanks to the opportunities offered by digitalisation,” said the Minister.

In this sense, the Defence Innovation Research Institute will soon be established as a pillar institution of the Hungarian Ministry of Defence, which will enter the innovation ecosystem from the military perspective. The institute will be headed by Imre Porkoláb, who was promoted to the rank of brigadier general on 18 October.

Kristóf Szalay-Bobrovniczky cited the acquisition of equipment, the establishment of an assembly and manufacturing capacity within the Hungarian defence industry, and the integration of digital technology into the operations of the Hungarian Armed Forces as further steps in the development of the armed forces. He also emphasised the importance of developing drone technology as a new area of innovation and the value of excellent communication as a basis for integration work. The Minister also discussed the role of space technology, for example in Earth observation. In December alone, the Hungarian government and its state-owned company N7 announced three joint ventures as part of a massive spending spree on new weapons and industrial facilities.

The acquisitions, involving major foreign defence contractors, come amid reports of a shortage of staff to operate and build the facilities. After a decade of neglect, the European nation has in recent years embarked on a drive to modernise and strengthen its defence industrial backbone. This has resulted in an increase of around $1.4 billion in defence spending for 2023 compared to the previous year, bringing the budget to nearly $4.5 billion.

According to Hungarian Defence Minister Kristóf Szalay, this will allow the government to raise its military spending to 2 percent of gross domestic product a year earlier than planned. This is the target set for NATO countries, of which Hungary is one. It is expected that 30 to 40 per cent of the money will be spent on capacity building and modernisation of the armed forces.

“The defence budget has been declining since the end of the Cold War, and at its lowest point in 2010 Hungary had only one operational military transport helicopter and less than a dozen combat-ready armoured vehicles,” said Péter Wagner, a senior research fellow at the Hungarian Institute for Foreign Affairs and Trade. As a result, the government had two options: either spend a lot of money abroad, or import as many domestic products as possible. The nation has largely relied on the latter.

Last December, the government and N7 signed three joint venture agreements:

- The German company Dynamit Nobel is the first customer for the RGW 110 HH-T anti-tank weapon.

- With the Colt CZ Group of the Czech Republic to supply firearms to the Hungarian military.

- With Germany’s Rheinmetall to produce explosives in response to a European ammunition shortage.

This last agreement is a continuation of an earlier commitment made in partnership with Czech suppliers for the “Hungarian Lynx” in 2021.In 2019, work began on a major new production facility for the Hungarian Lynx contract. At the end of its production cycle, the Zalaegerszeg plant will be one of the most advanced military factories in Europe and will have created around 500 jobs. The Hungarian Minister for Innovation and Technology, László Palkovics, has described the plant and the Lynx IFV initiative as the flagship project of the country’s Zrinyi 2026 military development programme.

Hungary is buying 218 Lynx, of which 176 will be produced at the new facility in Zalaegerszeg. The first models will be produced at an existing Rheinmetall plant in Germany, where future Hungarian Lynx operators will also be trained. Rheinmetall was selected as the supplier of the next-generation IFV for the Hungarian Army because of its commitment to providing significant local economic value added, complementing the Lynx’s exceptional level of innovation.

Similar to previous deals, all the deals signed in December involve the transfer of technology and skills, the establishment of a domestic production facility, the addition of local components, and the eventual procurement of weapons by the Hungarian armed forces, with the foreign company retaining controlling ownership.

According to local proponents, the pillars that make Hungary’s military sector an attractive investment location can be categorised independently. Several international organisations cite the country’s logistical infrastructure and central location – a gateway for foreign companies to Central and Southeast European markets – as a competitive advantage.

According to Tamás Csiki Varga, a senior research fellow at the Budapest-based Institute for Strategic and Defence Studies, “procurements are strongly linked to long-term defence industrial investment on a spectrum from assembly through production to future joint innovation, rather than a one-off arms purchase”. The newly formed defence industry enjoys both state benefits and subsidies, according to Varga. The country also offers a relatively cheap and highly skilled labour force and lower unit production costs than elsewhere. Moreover, “arms exports are not politically sensitive in Hungary,” he notes. “While they comply with international arms transfer regulations, there are no political or domestic social blockages that could hinder their exports to conflict regions.”

Since 2016, international companies have cited labour shortages as the “worst hurdle” to financing in Hungary, according to the US Trade Administration. This, of course, has a cost. Hungary is already among the NATO countries that spend two per cent of GDP on defence. A few months ago, the minister confirmed that Hungarian military development would continue despite the economic difficulties ahead. This is backed up by the fact that from September 2022, the salaries of Hungarian soldiers will be increased by approximately 25 per cent. The boosting of the social recognition of the military and the raising of military salaries are also key objectives of the Zrínyi 2026 force development programme. Of course, the attainment of these objectives can play a key role in increasing the number of troops as well.