Interview conducted by Jakub Skowron [1].

Introduction

Technological superiority has always been a defining factor in a country’s strength. Whether we look back to ancient times, when armies with more durable weapons held the upper hand on the battlefield, or to the modern era, where the race to develop nuclear weapons cemented the United States’ status as a superpower and brought an end to World War II, technological advantage has consistently shaped global power dynamics.

In recent years, the race for supremacy in artificial intelligence (AI) has become a crucial battleground in global geopolitics. Access to and advancement in AI technology not only drive economic growth but also enhance military capabilities. For nations aspiring to global power status, gaining an edge in this sector is a top priority and a fundamental pillar of political strategy.

One of the key policy moves by U.S. President Joe Biden’s administration in January this year was the introduction of regulations restricting or outright banning the export of AI chips to selected countries. These restrictions notably did not apply to traditional U.S. allies, such as most Western European nations. In contrast, a full-scale export ban was imposed on America’s primary geopolitical adversaries, including Russia and China.

While the division between allies and rivals was expected, a third category – countries permitted to receive AI chips but under specific restrictions – sparked controversy. This group included Central and Eastern European nations, which have long sought closer ties with Washington, particularly through transatlantic structures like NATO. At first glance, this categorization of European countries into ‘preferred’ and ‘less favoured’ echoes Cold War-era divisions and contradicts the narrative that Central and Eastern Europe has fully integrated into the Western world. However, the reality is far more complex.

In order to better understand this topic, we interviewed Polish new technology and digitalisation analyst Aleksandra Wójtowicz [2]. In the interview, we focused on the Polish perspective to show the potential consequences for a country under partial restrictions and to explain what the US decision means in practice.

Interview with Aleksandra Wójtowicz

1. What criteria did the US use to divide countries into restriction groups?

It is not clear what criteria were used. Two scenarios are possible. The first assumes that the division of states arose somewhat by accident. However, the second scenario, which assumes that national security was the main motivator for the US, seems more likely. After all, the main purpose of the restrictions is to make it more difficult for third countries, in practice mainly China, to use cutting-edge technology and to circumvent existing sanctions. Lack of access to the latest GPUs [3] would be to prevent them from developing more advanced AI models than those of the US and the first group countries. In this sense, a certain logic can be seen when it comes to the countries of the second group – after all, Israel or Saudi Arabia, some of the closest allies of the US, are also included. However, these are countries that are in a difficult region from a US perspective – and perhaps this is what motivated the States when forming the three groups.

2. What implications might GPU access restrictions have for Poland’s AI sector and digitalisation strategy?

The short-term consequences for Poland will be minor. The restrictions will not take full effect until 120 days after the publication of the regulations, and the computing power generated by the 50,000 top-tier GPUs envisaged for the second group countries is high and would probably allow to train an effective generative AI model. In addition, a maximum of 5,000 advanced GPUs are currently installed in Poland, mainly in universities and research centres. This represents 10% of the purchase limit up to and including 2027, which can be doubled in agreement with the US. Furthermore, purchases of up to 1,700 GPUs by a single public or private entity do not count towards the limit amount (it is unclear whether the US has provided methods to counteract circumvention of the limit by setting up dummy companies placing small orders). In the long term, the computing power of 50,000 advanced GPUs may not be enough for private entities in the second group countries (including Poland) to be able to create state-of-the-art AI models. This may negatively impact the chances of Poland’s digitalisation strategy by 2035. On the other hand, however, the Chinese Deepseek model shows that perhaps the highest computing power is not crucial for creating advanced models – so potentially this long-term threat is also low.

3. How is the EU reacting to the division of its members? Is it taking action against the US?

As early as 15 January this year, European Commission Vice-President Henna Virkkunen and Commissioner Maroš Šefčovič expressed concern about the restrictions and the view that selling GPUs to the entire EU was in the interest of the US. However, the issue now seems to have receded into the background, with countries individually seeking to change their status.

4. Can Poland look for alternative GPU suppliers, e.g. in China? What would be the consequences of such actions?

Poland should not, at least for the time being, look for alternative GPU suppliers in Group 3 countries – that is, countries considered a threat by the United States. This would lower Poland’s importance in relations with the US and, even more importantly, could negatively influence the current US administration’s opinion of Poland. The consequences could be very negative.

Endnotes

[1] Jakub Skowron is a student of advanced sociological research at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, working with Blue Europe.

[2] Aleksandra Wójtowicz is an analyst for new technologies and digitalisation. Her research interests include digital regulation, cyber security and disinformation. She is a fellow of the European Alpbach Forum, IRI’s Transatlantic Security Initiative and Humanity in Action. Previously associated with NASK, WiseEuropa, Polityka Insight and ECFR, among others. A graduate of the University of Warsaw, she also studied at George Mason University in Washington, D.C. and at Charles University in Prague.(Source: Polish Institute of International Affairs)

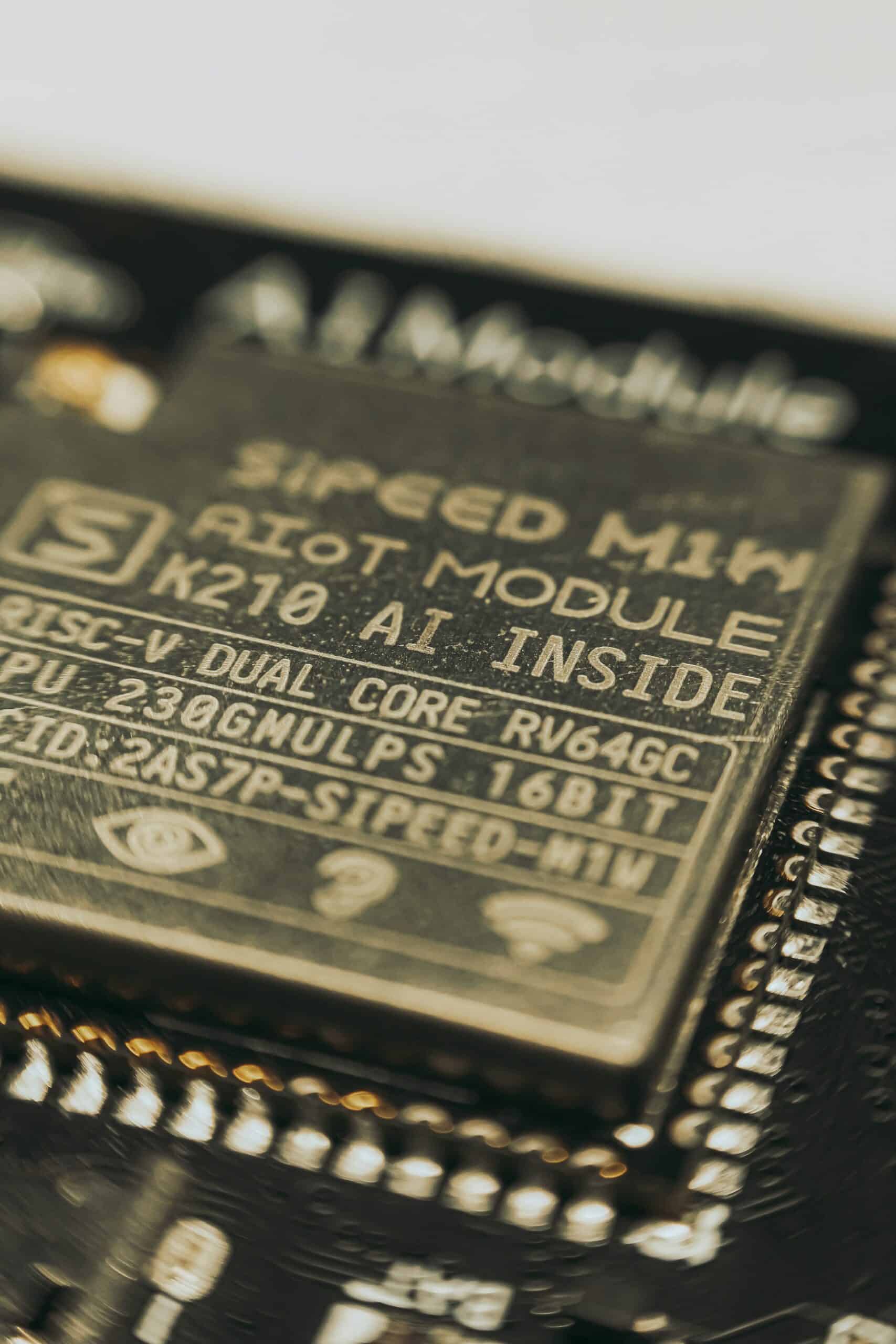

[3] Advanced GPUs (Graphics Processing Units) are high-performance graphics processors used for intensive computing in fields such as artificial intelligence (AI).