Turkey’s foreign policy agenda has been shaped for decades by the political arrangements of the Cold War. Turkey’s unmistakable orientation towards the West is not a temporary phenomenon. It is a tradition that dates back to the 1920s, when Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the Republic of Turkey, initiated the so-called “Westernisation” of the country by introducing significant reforms based on the Western European model.

As a geostrategic ally of the Western powers, Turkey played an essential role in the post-World War II bipolar world. Since Turkey’s membership of the Council of Europe in 1949 and its active engagement in NATO in 1952, its orientation towards the West has continued to evolve. The signing of the Association Agreement (Ankara Agreement) between the European Community (EC) and Turkey in 1963 demonstrated Turkey’s long-term strategic intention to become a full member of the European Community. In 1986, 25 years later, Turkey formally applied for EU membership. Since the early 2000s, Turkey has adopted a series of reform packages. Following the election victory of the moderate Islamist Justice and Development Party (AKP) in 2002, Turkey took a major step towards EU membership and talks began on 3 October 2005.

EU-Turkey relations have been heavily influenced by Turkey’s membership ambitions and its foreign policy agenda has been strongly aligned with that of the EU. However, Turkey’s recent involvement in the South Caucasus and Black Sea region indicates a shift from an EU-influenced agenda to a more independent Turkish foreign policy. The end of bipolarity in international politics in 1989 and the rapprochement of Central and Eastern European states with the EU, followed by their accession in 2004, had a significant impact on Turkey’s geopolitical orientation and the global perception of the country as a whole.

Turkey and its geopolitical objectives

Geopolitically, Turkey has a natural desire to extend its sphere of influence beyond its surrounding waters. The nation is thus best described as a “littoral” power, perpetually caught in a balancing act between East and West. This has led to a widespread perception that Ankara must respond forcefully to the current scenario. This reality predates the establishment of the Turkish Republic and has its origins in the late Ottoman Empire. Throughout the region’s modern history, Russia and Turkey have been engaged in an existential competition. Several factors contribute to the strategic importance of the Black Sea. It has a long history of cultural, political and economic relations. It successfully anchors the countries of Central and Eastern Europe in the Euro-Atlantic community. Undoubtedly, geopolitical factors need to be examined in relation to the location of oil and gas reserves and the routes by which crude oil can be brought to market, such as by tanker, pipeline and rail.

The lack of explicit Turkish support for the invasion of Iraq by the United States and several European Union member states in 2003 marked the beginning of Turkey’s new strategy. Since then, Turkey’s foreign policy has steadily adopted a more autonomous stance in international politics vis-à-vis the United States and the European Union. Turkey now appears to be pursuing a greater degree of manoeuvrability and building a multidimensional view of its geopolitics in the region, forging numerous interactions with its neighbours and strengthening its position in its immediate neighbourhood.

The geopolitical importance of the wider Black Sea region has increased in recent years due to energy security concerns. Safe passage through the Aegean high seas is essential for all Black Sea littoral states whose merchant and naval vessels require access to the Mediterranean and its environs. Russia and Ukraine are in conflict over undefined borders and regional dominance. Moscow has sought to control the transport of crude oil from the Caspian region to EU member states to ensure that the Russian economy benefits from Central Asian energy with minimal effort, while Transnet and Gasport can transport Russian oil and natural gas to the lucrative European market at a higher cost. Gazprom has also started charging much more for the gas it transports to countries in the Black Sea region.

Turkish economic development and internationalisation

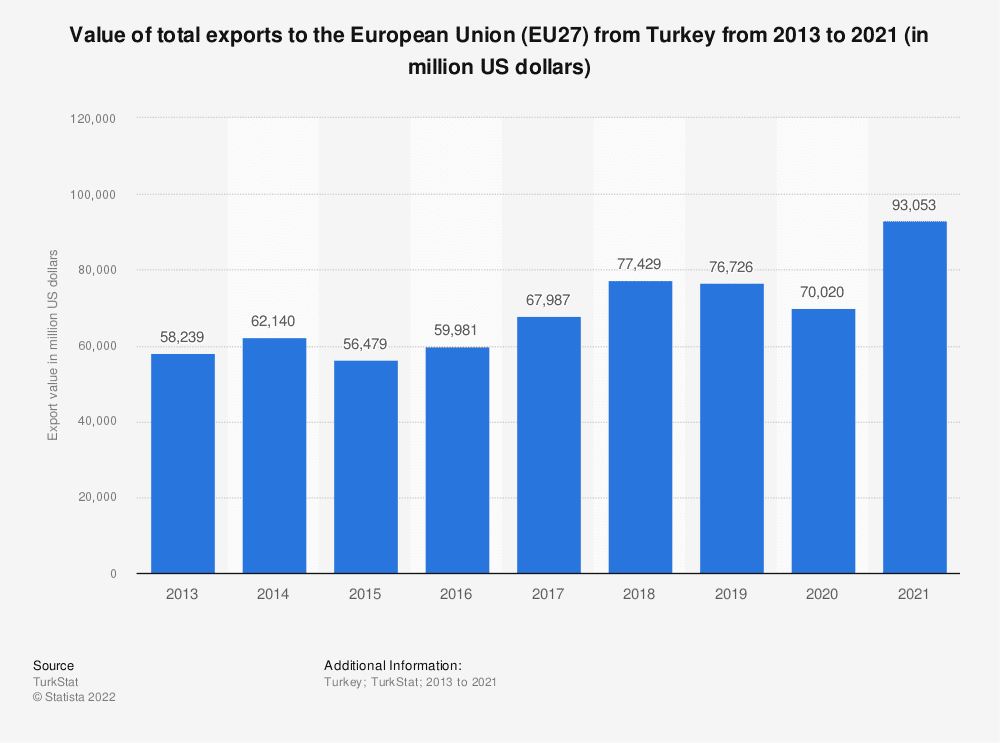

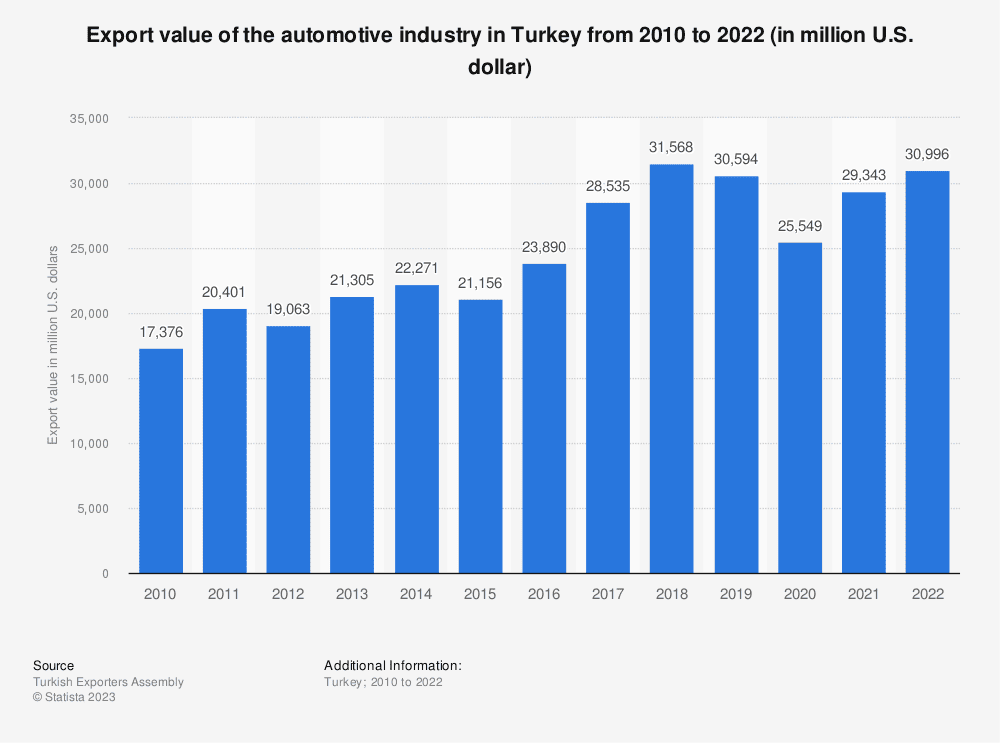

Over the decades, Turkey’s economy has transformed from one based mainly on agriculture and an abundant, low-skilled labour force, employed mainly in the textile industry, to an industrial economy. It is a major European car manufacturer, a world leader in shipbuilding and a major producer of electronics and household appliances, including televisions and washing machines. In the electronics sector, the domestic appliance industry has grown rapidly, with domestic companies (Vestel, Beko) being important exporters. There is a growing demand for Turkish products in domestic markets as well as in developing and transition countries, although these are not high-end brands but rather low- to mid-priced goods. Several multinational car manufacturers (Ford, Renault, Fiat, Hyundai, Toyota, Honda, Opel, Mercedes and MAN) have relocated part of their production capacity to Turkey, largely as a result of the EU-Turkey customs union agreement, which allows free export of goods to the European single market. Domestic brands (Otokar, BMC and Temsa) dominate bus production. As shown in the charts below, Turkish exports towards the EU have seen a surge in 2021 and the ones related to the Turkish automotive sector have returned to pre-pandemic levels after peaking in 2018.

In addition, the increasing globalisation of the Turkish economy has made the country an international investor. Before the 1980s, Turkey’s economy was rather closed. The import-substitution industrialisation that Turkey pursued was focused on domestic markets, and the majority of state-owned or state-subsidised private firms lacked the incentive and opportunity to expand into new markets. However, the rise in oil prices and the economic difficulties of the 1970s forced Egypt to open its economy. In a dramatic shift in economic policy, Turkey began to promote export orientation as its primary industrial growth strategy. As a result, the government significantly encouraged export production by paying thirty per cent of companies’ export costs and providing them with energy and transport cost savings.

Turkey’s foreign trade strategy has changed both in its ideology and in its implementation. Ahmet Davutolu, the central protagonist of the new foreign policy, emphasised the importance of strategic depth: instead of being on the periphery of Europe, Turkey, as a strategically located country, should use its position to build its own regional importance. As a result of this strategy, Turkey adopted a ‘zero-problem’ foreign policy towards its neighbours and sought to cultivate the image of a trading state that prioritised positive trade relations over fruitless international political conflicts. Together with a strong economic recovery in the early twenty-first century, this approach increased the importance of regional and global relations. The economic importance of neighbouring regions (the Balkans, the Caucasus, the Middle East and North Africa, and Central Asia) increased after the 2008 financial crisis. This has meant not only an increase in the volume of trade with these regions and countries, but also an increase in investment activity. In the following sections, we will examine the different types of Turkish FDI abroad, with a special focus on Eastern Europe.

Turkish foreign investment in Eastern Europe

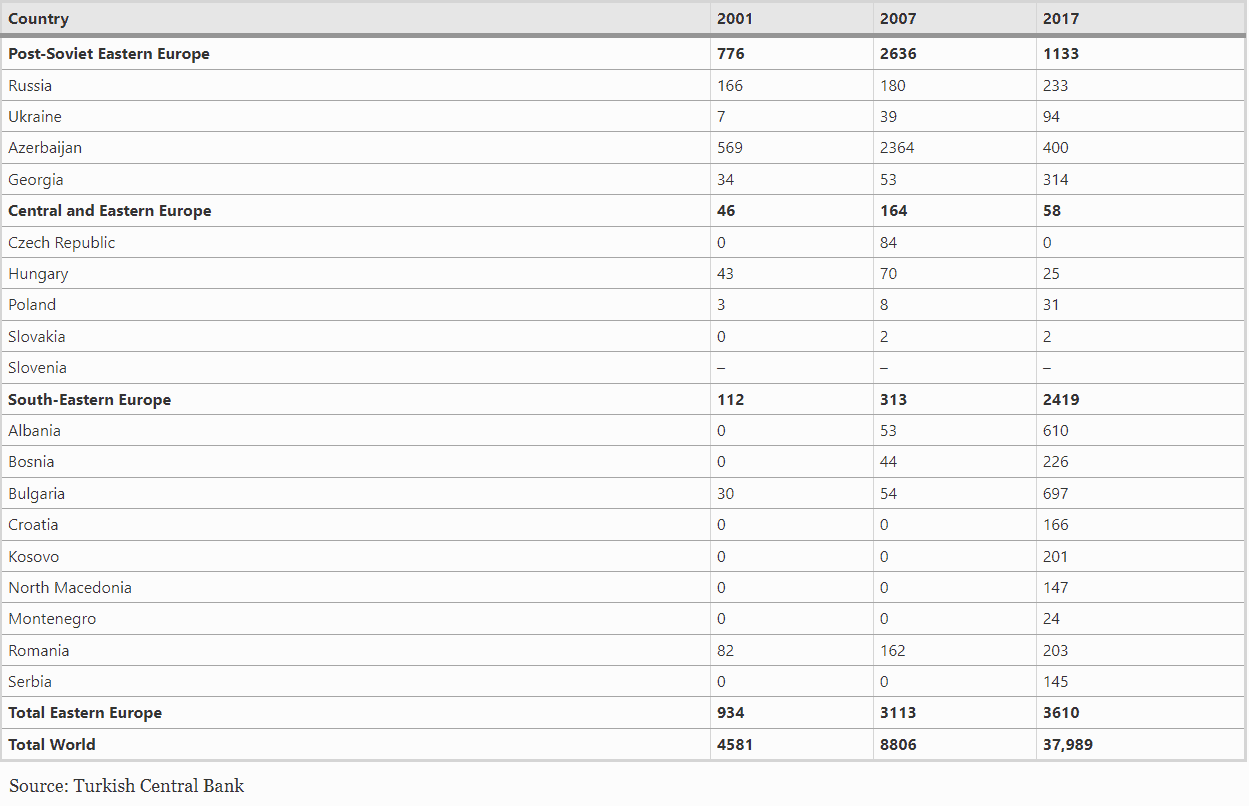

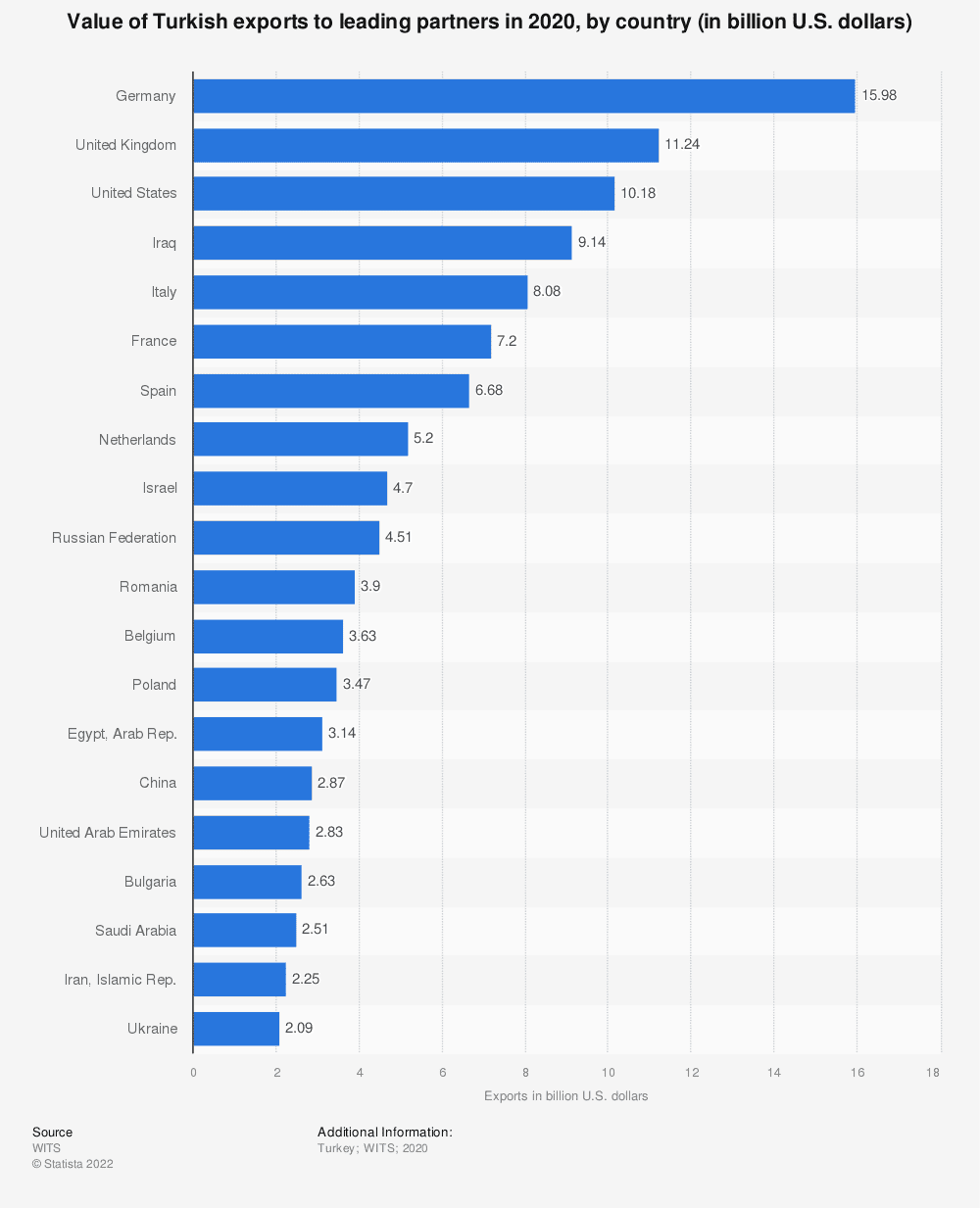

In terms of non-financial outward FDI, Germany and Austria are the main destinations, along with Switzerland and the Netherlands. There is also a link between the share of the Turkish population in Western European countries and these countries. Among the transition countries in Eastern Europe, Russia, Azerbaijan, Romania, Bulgaria and, more recently, the Western Balkans are Turkey’s main investment destinations. Despite the fact that the Visegrad countries are not among the top investment destinations for Turkish capital, the region’s experience with Turkish investment is worth analysing.

Although the total amount of investment in Eastern Europe is lower than in Western Europe, more companies have invested there. This suggests that smaller, more risk-taking companies have invested more in Eastern Europe, while larger, more capital-intensive companies with market expertise have invested more in Western Europe. The multinationals that invested in Eastern Europe were more flexible in adapting to local conditions; they were not deterred by legal ambiguities and bureaucratic hurdles in obtaining licences and permits, having dealt with similar issues at home. It is clear that these companies are exploiting their strategic advantages, which stem from the knowledge they have gained from operating in Turkey and its neighbouring regions. However, country-specific factors such as geographical and cultural proximity and the availability of cheap and skilled labour are also key advantages.

Today, Southeast Europe (the Balkans) is even more important for Turkish investors: many companies invest in the region as a steppingstone to becoming regional players. They invest mainly in infrastructure (communications, finance, retail, tourism and roads), although the role of manufacturing is growing. Despite this, Turkey remains a relative latecomer to the region. EU companies have taken control of key industries (such as Germany’s Deutsche Telekom in telecommunications or Greece’s OTE in banking). Greece continues to play a crucial economic role in the region, despite being hit hard by the financial crisis. Turkey has lagged behind in targeting key industries, with Russian objectives, for example in the energy sector, undermining its efforts. Several features of Turkey’s investment plan in Southeast Europe are relevant to other neighbouring regions. Financial investment is crucial; the introduction of Turkish banks into a country has paved the way for subsequent commercial relations by providing investors with valuable country-specific information.

Eastern Europe attractivity

After 2004, the attractiveness of the new EU member states in Eastern Europe increased. For many companies, the benefits of international company status were themselves an important factor in investing abroad. Many export-oriented SMEs or large companies wanted to strengthen their value chains and facilitate regional integration by investing abroad. Although the Balkans used to be the first step abroad for most Turkish companies, the countries of Central and Eastern Europe can also be a good option for those seeking to open up to European markets.

The region has also benefited from EU membership through increased EU financial support for infrastructure investment. Especially compared to the Middle East, the improved infrastructure in the Eastern European region created a much better business environment. In addition, Turkish construction companies participated in some of the EU-funded investments, such as Gülermak’s involvement in the construction of the Warsaw metro and motorways in Poland. The increased investment and consumption activity of the private sector has also been attractive for Turkish companies, which have initiated or participated in several commercial construction projects (shopping centres, commercial and residential buildings).

Moreover, the importance of government support in attracting foreign direct investment is growing. Most Central and Eastern European countries are trying to attract investors, and Turkey is one of the main targets due to its proximity, dynamic economic performance and growing interest in investing in the Eastern European region. Investment incentives offered by national and local authorities have also become a decisive factor. Most countries in the region are trying to attract foreign direct investment, especially in the manufacturing and technology-intensive services sectors, and investment promotion authorities grant various types of incentives. In one recent case from 2018, the Hungarian Investment Promotion Agency (HIPA) secured a 50% matched government funded incentive package to support Metyx’s multi-million-euro investment project to expand its composite materials production facility in Kaposvár.

Finally, the availability of a skilled workforce and relatively low labour costs were also attractive factors. The minimum wage and total labour costs are about 10% higher than in Turkey, which means that labour-intensive investments are more likely to be made in low-wage countries in southern and eastern Europe. However, a recent problem mentioned by several investors is the inability to find sufficient labour in Eastern European countries. Young people are moving to Western Europe for work, while attempts are being made to fill the labour shortage with temporary workers from neighbouring countries such as Ukraine and Belarus.

To conclude, Eastern Europe represents a bridge for Turkish investments to the western continent and an occasion for mutual economic benefit. In line with Turkey’s aim to increase its independency with a multifaced stance in the international scenario, there is a high probability that current ties and partnerships will strengthen – paving the way for an increased economic development in the Eastern European region.

References

Szigetvári, T. (2020). Turkish Investments in Central and Eastern Europe: Motivations and Experiences. In: Szunomár, Á. (eds) Emerging-market Multinational Enterprises in East Central Europe. Studies in Economic Transition.

Ayden, Y., Demirbag, M., & Tatoglu, E. (2018). Turkish Multinationals. Market Entry and Post-Acquisition Strategy. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Culpan, R., & Akcaoglu, E. (2018). An Examination of Turkish Investments in Central and Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States. In S. T. Marinova & M. A. Marinov (Eds.), Foreign Direct Investment in Central and Eastern Europe (pp. 181–200). London; New York: Routledge.

Djurica, D. (Ed.). (2015). Strengthening Economic Cooperation between South East Europe and Turkey. Sarajevo: Regional Cooperation Council.

Egresi, I., & Kara, F. (2015). Foreign Policy Influences on Outward Direct Investment: The Case of Turkey. Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies, 17(2), 181–203.

Anil, I., Tatoglu, E., & Ozkasap, G. (2014). Ownership and Market Entry Mode Choices of Emerging Country Multinationals in a Transition Country: Evidence from Turkish Multinationals in Romania. Journal of East European Management Studies, 19(4), 413–452.

Berktay (2013). The Turkish – Slovakian Relationship Experiences Its Golden Era. TUID

Uray, N., Vardar, N., & Nacar, R. (2012). International Marketing-Related Outward FDI Motives: Turkish MNCs’ Experience in the EU. In R. van Tulder, A. Verbeke, & L. Voinea (Eds.), New Policy Challenges for European Multinationals (pp. 305–338)

Glowik, M. (2009). Market Entry Strategies: Internationalization Theories, Network Concepts and Cases of Asian firms. München: Oldenbourg.