The Global Gateway is a new European strategy that was introduced by the European Commission and the High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy on December 1, 2021. Its goal is to strengthen global health, education, and research systems while advancing smart, clean, and secure energy, digital, and transportation links.

The initiative promotes trustworthy, long-lasting connections that benefit both people and the environment while addressing the most pressing issues facing the world today, such as climate change, environmental protection, improving health security, and enhancing competitiveness and global supply chains. In order to support a long-lasting global recovery, Global Gateway hopes to mobilise up to €300 billion in investments between 2021 and 2027, while taking into consideration the demands of partners and the EU’s own interests.

Comparatively, since 2005, China has invested about $2.3 trillion in nearly 4,000 foreign development and construction projects, providing Beijing a significant advantage just as the EU begins its push to broaden its economic influence.

On the objective of the project, Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, said: “We will support smart investments in quality infrastructure, respecting the highest social and environmental standards, in line with the EU’s values and standards. The Global Gateway strategy is a template for how Europe can build more resilient connections with the world.”[1]

Global Gateway will unite the EU and Member States with their financial and development institutions, such as the European Investment Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, through a Team Europe strategy and work to mobilise the private sector in order to leverage investments for transformational impact.

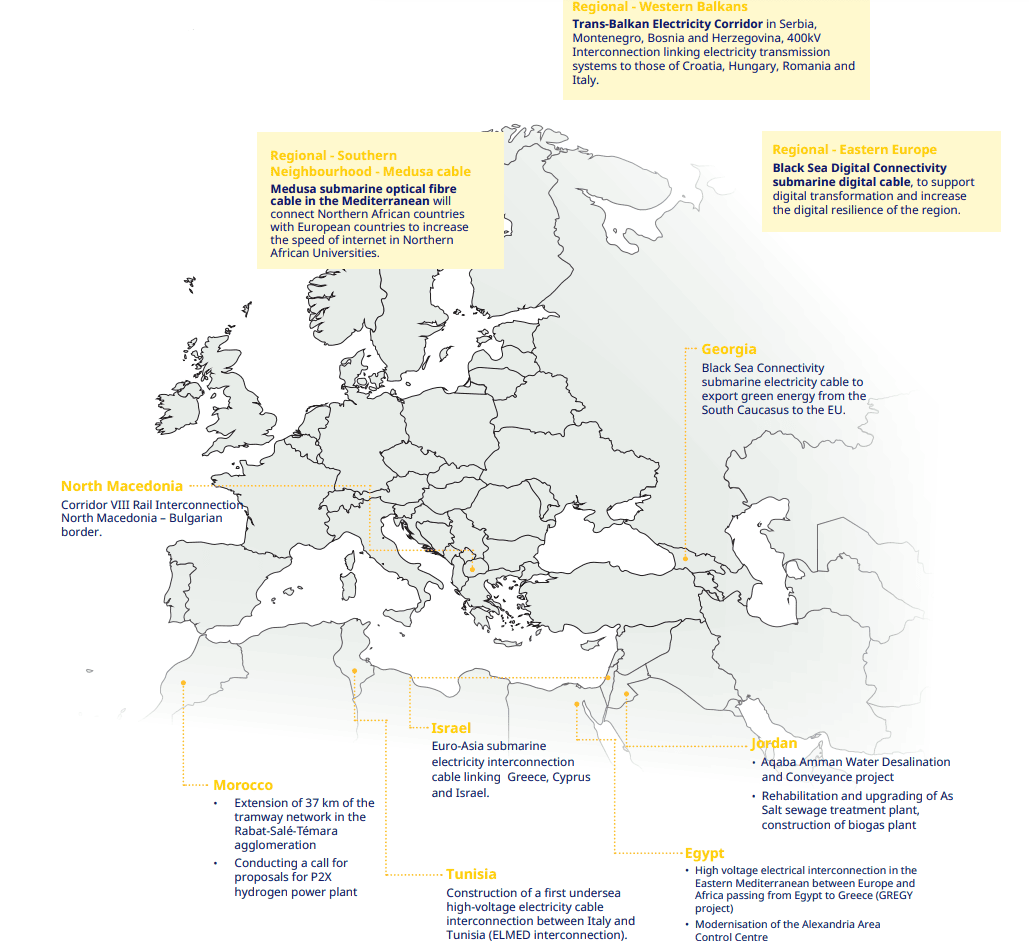

The Global Gateway team has selected 70 lighthouse projects that can be deployed this year on an internal list.[2] Officials in Brussels are currently deciding which 30 projects will receive priority for execution. More than half of the project suggestions are in sub-Saharan Africa, which is the region with the greatest attention. Seven projects are in the Balkans and North Africa, 13 are in Asia and Oceania, and 14 are in Central and South America.

Source: European Commission (flagship projects for 2023)

Along with additional electricity lines to the Western Balkans and Tunisia, the EU is pursuing agreements for raw materials with Namibia and Chile. With significant projects in Central Asia, Indonesia, and Vietnam, it also intends to compete with Russia and China, partially in those countries’ backyards.

A change in the EU outward policy

European foreign policy has changed its approach with the launch of Global Gateway. Since the beginning of traditional development aid, the EU has positioned itself as the leader of the good, the genuine, and the pleasant. It has traditionally been described as being concerned with the wellbeing of the receiving nations. In spite of the fact that this truth was frequently overlooked, Europe also profited. The EU is now becoming more transparent about that self-interest through the Global Gateway programme.

In order to create a counteroffer to Beijing, which sees its New Silk Road effort as both an economic and a sociopolitical project where its own values and economic policy norms can be imposed, Global Gateway will also protect global supply lines.

High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Josep Borrell stated: “Connections across key sectors help to build shared communities of interest and reinforce the resilience of our supply chains. A stronger Europe in the world means a resolute engagement with our partners, firmly grounded in our core principles. With the Global Gateway Strategy we are reaffirming our vision of boosting a network of connections, which must be based on internationally accepted standards, rules and regulations in order to provide a level-playing field.”[3]

The continent has changed its strategy at a time when the political environment across the world is becoming tense. Energy costs have briefly reached ludicrous heights as a result of the epidemic and Russia’s invasion on Ukraine, highlighting how dependent businesses and nations are on external factors. China is establishing itself as a new powerhouse at the same time, enticing nations into debt traps, gaining access to raw supplies globally, and dominating an increasing number of markets.[4]

Currently, there is disagreement among the member nations over the initiative’s geographical focus. France and Italy are urging investment, particularly in Africa. On the other side, Latin America is being argued for by Spain and Portugal. And the Western Balkans area wants greater funding from the EU.[5]

A critical focus on the “Southern Neighbourhood”

Through the BRI, China has significantly boosted its investments in the southern neighbourhood, particularly in the fields of building, transportation, and energy. Beijing invested in or directly built projects in southern neighbouring nations with a combined total worth of $82.1 billion between 2005 and the first half of 2022.[6] The China Global Investment Tracker, the only complete information that is publicly accessible, only includes deals worth more than $100 million, so the true number may be significantly higher.[7]

China has developed tremendous political power in the area, as seen by Algeria’s recent decision to seek for BRICS membership and Egypt’s recent declaration of interest in the organisation.[8] Additionally, Algeria and China inked two agreements in December 2022 on BRI development and economic cooperation, which significantly improved their relationship.[9]

At first glance, the relationship between the EU and the nations in the area could seem to be one of increasing estrangement and stalled integration efforts. The crisis in Ukraine and the close relationships that many regional players have with Moscow have further hurt the EU’s commitment.

China is not, however, replacing the EU as the main partner in the building of infrastructure for the southern neighbouring nations. According to data from EU Aid Explorer, which offers statistics for Official Development Aid from EU institutions and member states, the EU provided the southern neighbourhood with €57.92 billion in total aid between 2007 and 2022.[10] Not only is this on par with Chinese pledges in terms of size, but it is much the more impressive given that it consists virtually entirely of gifts. Contrarily, BRI finance takes the form of loans, which partner governments must of course repay, and which are not always on advantageous terms. Beijing was a global leader in organising significant infrastructure investment. But as time goes on, the shortcomings of its projects become more apparent, from a lack of transparency to the implied “debt trap” associated with its use of loans (and refusals to allow borrowers to restructure their debt) to its dubious environmental sustainability.[11]

The EU also outperforms China in terms of commerce: for the majority of the countries in the southern neighbourhood, it outpaces China by a factor of at least two in terms of the proportion of total external trade with the region. According to statistics, the EU accounts for more than half of all commerce in Algeria and a quarter in Egypt.[12] Such a robust commercial partnership is expected to persist given that both nations are expanding their gas supplies to Europe in the backdrop of Russia’s assault on Ukraine.

These commercial ties provide as a strong foundation for developing closer ties in manufacturing and green energy. A strong rationale for limiting China’s expansion in the area and for the EU to intensify its efforts to do so is the explicit recognition of China as a systemic rival by the EU. However, achieving this aim shouldn’t come at the expense of mutually beneficial partnerships, foremost among them the battle against climate change.

At the EU-China Summit in April 2022,[13] both sides acknowledged the existence of such common ground. Supporting the decarbonization of activities in the southern neighbourhood through investments and technical assistance would address shared concerns on climate issues while generating economic opportunity. The EU and China are both net energy importers, therefore they lack the ability to weaponize fossil resources (unlike Gulf Arab regimes). The EU would benefit from a less carbon-intensive southern neighbourhood, which some Chinese technology can help build.

In the next part we will analyse the Global Gateway’s main flaws and criticism. You can find it here.

References

- https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/stronger-europe-world/global-gateway_en ↑

- https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-sets-outs-projects-to-make-global-gateway-visible-on-the-ground/ ↑

- https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_6433 ↑

- https://www.aiddata.org/publications/china-as-an-international-lender-of-last-resort ↑

- https://www.spiegel.de/international/europe/the-eu-s-global-gateway-europe-s-answer-to-china-s-new-silk-road-is-slow-going-a-9171458b-6766-490e-b443-7478a0866987 ↑

- https://www.iemed.org/publication/the-role-of-china-in-the-middle-east-and-north-africa-mena-beyond-economic-interests/#section-notes-cqyFJ ↑

- https://www.aei.org/china-global-investment-tracker/ ↑

- https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/01/11/algeria-energy-oil-brics-russia-china/ ↑

- https://www.silkroadbriefing.com/news/2022/12/08/algeria-china-upgrade-and-extend-belt-road-initiative-development-plans/ ↑

- https://euaidexplorer.ec.europa.eu/explore/recipients_en ↑

- https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2023/02/02/china-is-paralysing-global-debt-forgiveness-efforts ↑

- https://oec.world/en ↑

- https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_2214 ↑