“Who rules East Europe commands the heartland, who rules the heartland commands the World-island, who rules the World-island commands the World”. These are the exact words used by renowned British geopolitician Halford Mackinder to convey the significance of the region situated in the eastern portion of the North European plain, the region bounded by the Baltic and Black seas. After regaining their independence at the beginning of the 20th century, Polish legislators tried to reimagine their region as the Intermarium, a powerful land force united to protect central Eastern Europe’s honour amid the revival of Germany and Russia.

Halford Mackinder’s Heartland theory depicted on a global map.

Striving for geopolitical relevance and independence

The rulers of the Baltic and Black seas have frequently considered the concept of creating a powerful, autonomous governmental system for millennia. A unitary authority was more likely to arise in this region due to the river network’s communicative coherence, shared interest in defending against invasions from the continental East, and Germanic influence from the West. The Jagiellonian dynasty, founded by the Duke of Lithuania, Wadysaw II Jagieo, is where the idea first emerged. The Teutonic order, which had taken Polish territory, quickly emerged as a shared foe in the area, leading to the creation of the Polish-Lithuanian union that was formally created in Krewo.

The Teutonic knights continued to wage crusades in Lithuania despite the country having become Christian. The Union achieved its goal by defeating the order that had been established by the victory at the Battle of Grunwald in 1410 by winning the two-year conflict. One of the biggest conflicts in mediaeval Europe, with up to 70,000 armed participants. The war did not cause the Teutonic order to lose its lands, but during the following century it started to wane. This came about as a result of the economy’s ongoing decline brought on by Poland and Lithuania’s trade embargo.

The order lost battles with the Polish-Lithuanian Union in the years 1519 and 1521, and in 1525 it finally submitted to the Polish monarch and became a lifelong subordinate. Following the union of Lublin in 1569, which resulted in the foundation of the Commonwealth, a unified state of Poland and Lithuania, these 150 years cemented the ties between Poland and Lithuania. With the exception of the Holy-Roman empire, the Commonwealth region was almost 1 million square kilometres in size and the largest nation on the continent. The present-day nations of Poland, Belarus, Ukraine, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Moldova, and Russia were all or part of the Commonwealth at the time.

At the time, the nation had no comparable adversary in the East. However, the devastating conflicts of the 17th century and the ineffective system of government ultimately led to a decline. The Commonwealth, unlike the majority of other European nations, was distinguished by a significant decentralisation of power. Eight to ten percent of the population was nobility, and because of their powerful position and the monarch’s limited authority, some members of the noble class started prioritising their own interests over those of the state.

The neighbouring nations, who bought individual noblemen and advocated for policies that favoured their national interests, had an impact on the decisions made by the nobility. The following century saw the astonishing emergence of regionalized authority and judicial corruption. This position ultimately resulted in the free partitions that Russia, Prussia, and Austria made. Poland and Lithuania completely vanished from European maps after the fall of the Commonwealth in 1795; for the next 123 years, their identities only survived in language and memory. In the interim, Poles launched attempts to reclaim their independence, hoping to benefit from the continent’s geopolitical predicament.

The November Uprising of 1830 and the January Uprising of 1863, both unsuccessful revolts against the Russian Empire, were the two biggest movements for independence at the time. Prince Adam Jerzy Czartoryski, a self-styled “king without the crown prince,” who had close relations to the Russian empire, served as the movement’s leader. He even served as the Russian Tsar Alexander the First’s minister of foreign affairs in the past.

“Pożegnanie Europy” by Aleksander Sochaczewski (1894), shows exiled Poles arriving at the border of Europe.

Czartoryski was given the death penalty by Tsar Nicholas the First of Russia because he presided over the provisional government during the November revolt in the early 19th century. Czartoryski vigorously promoted the Polish cause while in exile in the Western countries, primarily France and England, as well as the Ottoman empire. His goal was to revive the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which would have joined forces with other Central European countries like as the Czechs and Slovaks, the Hungarians, the Romanians, the Serbs, and others in a confederation or alliance.

In order to balance the Germanic States in the West and the Russian Empire in the East, it was intended to construct a block of states, primarily Slavic. The lack of acceptance in the West would ultimately cause the concept to fail. The prospects of the coalition succeeding, even if Poland were to reappear, were limited because of territorial conflicts with Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania, and the Czech Republic.

Many countries in Central Europe regained their independence as a result of the end of World War I, including Poland, Lithuania, Czechoslovakia, Latvia, and Estonia. The hope of building a force in the region that could resist both the empires from the East and the West arose as a result of the weariness of war in European powers and the new geopolitical configuration.

Józef Pilsudski and his legacy over the Intermarium idea

The founding leader of the second Polish Republic, Józef Pilsudski, shared the goals of the Polish head of state and later served as field marshall, leading the Polish army in the successful conflict with Bolshevik Russia. The plan he envisioned was in nature identical to the concept of Czartoryski, and it eventually came to be known under the name Intermarium, which is Latin for between the seas. In 1920, it was sealed by victory in the Battle of Warsaw, also known as the Miracle of Vistula.

After the war with Russia, Pilsudski realised that building a bloc of nations that could counterbalance Germany and Russia was the only way to defeat the threat posed by their expansionism. In its current form, the motion called for the creation of a federation that would include Poland, Lithuania, and Ukraine. Poland would continue to be the de facto senior partner in that relationship even if it were to give part of its territory to Ukraine.

The Pilsudski idea was opposed by everyone. The Soviet Union attempted to obstruct the Intermarium agenda because their zone of influence was in danger. The Allied Powers believed that Bolshevism was only a transient threat and did not want to see Russia, an essential historic partner from a balance of power standpoint, diminished. They disapproved of Pilsudski’s rejection of his White allies, held him in low regard, rejected his ambitious intentions, and pushed Poland to limit its territory to Polish-majority areas. The Ukrainians, who were also seeking independence but were concerned that Poland might once again subjugate them, and the Belarusians, who lacked a strong sense of national identity, were not interested in either independence or Pilsudski’s proposals for union. The Lithuanians, who had restored their independence in 1918, were also unwilling to join.

A string of post-World War I wars and border disputes—the Polish-Soviet War, the Polish-Lithuanian War, the Polish-Ukrainian War, and border clashes between Poland and Czechoslovakia—between Poland and its neighbours in disputed territory did little to help Pilsudski’s plan.

In order to weaken Russia, Pilsudski wanted to divide the Soviet Union along national lines. The idea was the Great Eastern Empire, which included the countries of Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, and Belarus, rather than the nation of Poland. Germans and Russians were divided by this “kingdom,” which stretched from the Baltic to the Black sea and had historical roots. Pilsudski was aware that four distinct nationalities with individual state aspirations were born in the formerly Commonwealth-occupied territories.

While some academics take Pilsudski’s claims of democratic ideals for his federative plan at face value, others view them with scepticism and point to a coup d’état in 1926 in which Pilsudski seized practically totalitarian powers. Oleksandr Derhachov argues that the federation would have created a bigger Poland in which the interests of non-Poles, especially Ukrainians, would have gotten little consideration. Most Ukrainian historians, in particular, have negative opinions of his concept.

However, none of them have a possibility of long-term independence unless they have a sufficiently strong geopolitical potential. Pilsudski, who revived the Commonwealthan ideology, also observed its unfavourable consequences, namely the dominance of the Polish nation over the others. He thought that pluralistic democracy and true federalism were the best remedies for averting this kind of crisis, but this strategy failed for two reasons. The first was the mistrust of Lithuanian and Ukrainian political figures regarding the intentions of the Polish government.

They feared that the system’s control by the Polish nation would jeopardise their recently attained freedom. The second was an internal Polish factor. In opposition to the Polish socialist party, which Pilsudski came from, the national democrats and Polish nationalist ideology political movement coalesced around Roman Dmowski. As they saw no hope of building an effective government with Lithuanians or Ukrainians, they decided to create a monoethnic state.

The idea was finally dropped after the Treaty of Riga was signed in 1921 by Poland, Soviet Ukraine, and Soviet Russia, delineating the Polish-Russian border. The states of the Baltic-Black Sea block were going to benefit from the greatest strategy in twenty years because to this lack of geopolitical power consolidation.

A federation of states stretching from Finland in the north to Greece in the south was the concept that sparked interest in the political sector. When he was Poland’s minister of foreign affairs at the time, Józef advocated a Third Europe alliance of Central European nations to counterbalance the geopolitical influence of the USSR, authoritarian nations like Germany and Italy, and the Western powers England and France.

The alliance would be led by Poland, Hungary, and Romania, with Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Finland, and potentially Italy joining later. However, there was no foundation for this idea to manifest itself as a true force. Italy remained on the German side, the Transylvania conflict between Romania and Hungary persisted, and no one was willing to accept Poland’s leadership. Soon after, World War II started, shattering any significant plans to reestablish a dominant power in this part of Europe.

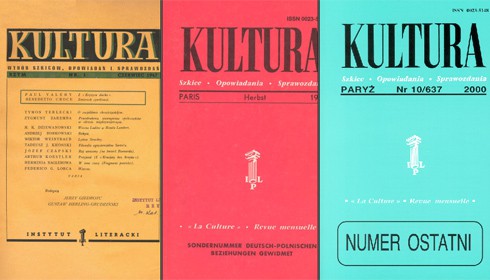

The Polish elites abandoned the Intermarium’s will in conformity with Moscow’s will throughout the course of the following 44 years whereas the elites in exile did not. In the Paris-based publication Kultura, Jerzy Giedroyc and Juliusz Mieroszewski, who were both living in France at the time, established the idea of a sovereign Polish state in which they firmly believed. Giedroyc once remarked, “Without free Lithuania, Belarus, and Ukraine, there cannot be a free Poland.

Three issues of “Kultura” Photo: Literary Institute

Rebuilding positive ties with the nations of Central and Eastern Europe was the cornerstone of the Giedroyc-Mieroszewski ideology. According to this plan, Poland would have to give up any imperial aspirations and contentious territorial claims in addition to accepting the post-war state structure and, consequently, the loss of Vilnius and Lviv, two crucial cities for Poles.

In essence, the theory was not hostile to Russia and backed the independence of Belarus and Ukraine. Giedroyc and Mieroszewski urged Poland and Russia to give up their plans to dominate the Eastern lands, primarily Ukraine, Lithuania, and Belarus. As a result, the ideology is also known as the ULB philosophy, which is derived from the initials of these nations.

In Wadysaw Sikorski’s Polish Government in Exile, the idea of a “Central [and Eastern] European Union”—a triangle geopolitical bloc rooted in the Baltic, Black, and Adriatic or Aegean Seas—was revived during World War II. Discussions in 1942 between the exiled governments of Greece, Yugoslavia, Poland, and Czechoslovakia over potential Greek-Yugoslav and Polish-Czechoslovak federations ultimately failed because to Soviet opposition, which caused Czech reluctance and Allied ambivalence or hostility. The construction of a federal union for Central and Eastern Europe that was not dominated by any one state was advocated in a statement made at the time by the Polish Underground State.

It represented a paradigm shift from the widespread viewpoint of Polish immigrants from the 1950s and 1960s who were determined to establish Polish dominance in the eastern regions of the old Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and did not want to give up their quest for that goal. In contrast to Mieroszewski, who passed away in 1976, Giedroyc lived to see Poland gain its independence in 1989, and their philosophy was the one that came the closest to the tactics used by the Polish government in the East following 1989.

Among other things, Poland supported libertarian inclinations in Ukraine, Russia, and other nations. However, with the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the newly established Belarusian government proposed an economic and customs union with Minsk. Poland at the time looked almost primarily to the West for economic power, therefore Warsaw rejected. As a result of this perspective, we joined the NATO, the European Union, the German-controlled West European supply chain, and the American military’s safety net.

The Polish state had been without stability for about 250 years before these decisions were made. The abandoning of geopolitical philosophy, of which Intermarium was a crucial notion, was brought about by prosperity and geopolitical stagnation brought about by American hegemony. Poles in the East prioritised the interests of the West over their own and those of the EU, US, and other countries.

Modern Intermarium initiatives

The ULB doctrine’s relationship with Belarus, the second-most significant nation after Ukraine, became almost entirely muddled. Poland, along with other countries in Central and Eastern Europe, must reevaluate its place in the region as global system tensions rise. Under a variety of titles, most recently the free-seas initiative, the notion of a similar alliance to the Commonwealth slowly started to resurface on the agenda.

The limited potential of Poland in comparison to Germany’s and Russia’s economic and military might makes the idea of Intermarium exceedingly challenging to carry out without an external patreon, according to the grassroots geopolitical thought in Poland. The USA is the sole contender for this title.

American agenda in the European theatre presupposes that a bloc of Central and Eastern European nations is aligned with US objectives in order to counterbalance the potential consolidation of Germany and Russia. The ambition to deliver energy to Ukraine and Belarus through terminals in Poland and Lithuania was the initial symptom.

The Visegrád Group nations of Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Hungary announced the formation of a Visegrád Battlegroup on May 12, 2011, under the leadership of Poland. By 2016, the battlegroup had been established as a separate entity from the NATO command. The four nations were also supposed to start conducting combined military drills under the supervision of the NATO Response Force starting in 2013. This was viewed by some academics as the first step toward close regional collaboration in Central Europe.

In his inauguration address on August 6, 2015, Polish President Andrzej Duda announced ambitions to create a regional alliance of Central European nations based on the Intermarium idea. The Three Seas Initiative had its inaugural summit in Dubrovnik, Croatia, in 2016. Along a north-south axis from the Baltic Sea to the Adriatic Sea and the Black Sea, the Twelve Seas Initiative has 12 member states: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Austria, Hungary, Slovenia, Croatia, Romania, and Bulgaria.

Every nation threatened by Russia would be covered by a 21st-century Intermarium. To avoid making the same mistakes as the original project, however, would be the most crucial aspect to take into account in an Intermarium for the twenty-first century. This entails putting aside personal issues and, ideally, coming together in the face of a shared, collective global peril. Until “the entire post-Soviet realm in Europe learns how to work in solidarity together,” Intermarium will not be successful. It should be remembered that no successor state can successfully confront Moscow by itself. Therefore, a projected Intermarium in the twenty-first century would only have a chance of succeeding when these nations have set their differences aside.

It is hardly surprising that Intermarium is a topic that is reviving today given that the Russian state continues to violate international law. Today, Ukraine would undoubtedly gain the most from this initiative, but the entire area is concerned about Russia’s security threat. The nations of central Europe have frequently been the scene of war, as history has demonstrated time and time again, thus they can only exist as a single alliance.

Due to their shared experiences during World Wars I and II, they all have historical motivations to form this kind of partnership today. Perhaps it is impossible to predict how Intermarium will function or who the actual members will be. In any case, Intermarium in the twenty-first century is very different from the circumstances that Józef Pilsudski faced and has a better chance of success.

A geopolitical initiative from the 20th century called Intermarium is gaining ground every year. Post-Soviet politicians, diplomats, and intellectuals are still debating the precise operations and politics of Intermarium in the twenty-first century. However, it’s crucial to remember that this is a project worth revisiting and modernising for demands in the twenty-first century.

Today, security concerns in Central and Eastern Europe are the main reason it is being promoted. Each member state must fully cooperate with the other for Intermarium to succeed in the twenty-first century, and American military assistance is also required. Intermarium has the power to fundamentally alter the global scene and build a more powerful Europe in the long run.

Bibliography

‘Adam Jerzy, Prince Czartoryski | Polish Statesman | Britannica’ <https://www.britannica.com/biography/Adam-Jerzy-Prince-Czartoryski>

‘Address by the President of the Republic of Poland Mr Andrzej Duda before the National Assembly’, Oficjalna Strona Prezydenta Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej, 2015 <https://www.president.pl/news/address-by-the-president-of-the-republic-of-poland-mr-andrzej-duda-before-the-national-assembly,35979>

Avdaliani, Emil, ‘Poland and the Success of Its “Intermarium” Project’, Modern Diplomacy, 2019 <https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2019/03/31/poland-and-the-success-of-its-intermarium-project/>

‘Battle of Grunwald | Summary | Britannica’ <https://www.britannica.com/event/Battle-of-Grunwald-1410>

‘Biography – JULIUSZ MIEROSZEWSKI’, Kultura Paryska – JULIUSZ MIEROSZEWSKI <https://kulturaparyska.com/pl/people/show/juliusz_mieroszewski/biography>

Golinowska, Stanisława, ‘Our Europe: 15 Years of Poland in the European Union’

Ištok, Robert, Irina Kozárová, and Anna Polačková, ‘The Intermarium as a Polish Geopolitical Concept in History and in the Present’, Geopolitics, 26.1 (2021), 314–41 <https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2018.1551206>

‘Jagiellon Dynasty | European History | Britannica’ <https://www.britannica.com/topic/Jagiellon-dynasty>

Janas, Antoni, ‘Giedroyc Doctrine and Polish “Ukrainian Turn” : From Conception to “Orange Revolution”’ <https://www.academia.edu/42767136/Giedroyc_Doctrine_and_Polish_Ukrainian_turn_from_conception_to_Orange_Revolution_>

‘Jerzy Giedroyc – Biography | Artist’, Culture.Pl <https://culture.pl/en/artist/jerzy-giedroyc>

‘Józef Piłsudski | Polish Revolutionary and Statesman | Britannica’ <https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jozef-Pilsudski>

Kft, Webra International, ‘The Visegrad Group: The Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia | History of the Visegrad Group’ ((C) 2006-2010, International Visegrad Fund, 2006) <https://www.visegradgroup.eu/history/history-of-the-visegrad>

‘Mackinder: Who Rules Eastern Europe Rules the World’, IGES, 2021 <https://iges.ba/en/geopolitics/mackinder-who-rules-eastern-europe-rules-the-world/>

‘November Insurrection | Polish History | Britannica’ <https://www.britannica.com/event/November-Insurrection>

‘Poland – The Commonwealth | Britannica’ <https://www.britannica.com/place/Poland/The-Commonwealth>

‘Poland in NATO – More than 20 Years – Ministry of National Defence – Gov.Pl Website’, Ministry of National Defence <https://www.gov.pl/web/national-defence/poland-in-nato-20-years>

‘Roman Dmowski | Polish Statesman | Britannica’ <https://www.britannica.com/biography/Roman-Dmowski>

‘Three Seas’, Three Seas Initiative <https://3seas.eu/en>