You can find Part 1 here.

In 2023, Croatia has reached a crucial integration milestone with the EU. After a decade of EU membership, the Balkan nation has joined the Euro and Schengen zones. As the EU Single Market celebrates its 30th anniversary this year, this signifies a dramatic shift in how Croatian residents and enterprises participate with and use its benefits.

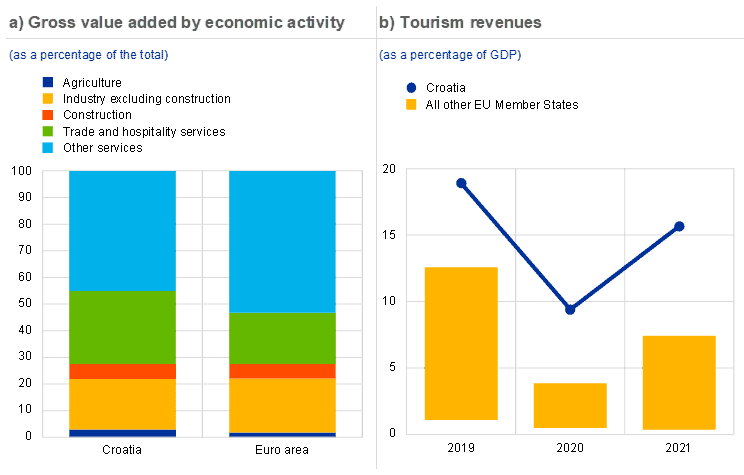

Through trade and financial ties, Croatia’s economy is well-integrated with the Eurozone. It has a population of around 4 million, and its GDP contributes for approximately 0.5% of the Euro area’s total. Similar to the makeup of the Eurozone as a whole, industry (including construction) and services account for around 25% and 72% of Croatia’s gross value added, respectively. In 2019, over 19 percent of Croatia’s gross domestic product (GDP) was generated by tourism. This proportion decreased substantially in 2020 due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic but climbed in 2021 and 2022. It is the most populous among EU member states. Tourism also has substantial effects on other economic sectors.

Source: European Central Bank, 2023

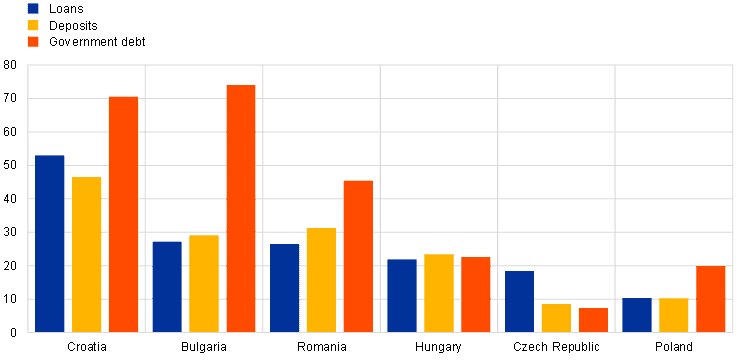

Prior to adopting the Euro legally, Croatia’s economy had a high degree of Euroization. A substantial portion of governmental and private debt was issued in Euro, reflecting the currency mix of family savings and liquid assets held by non-financial corporations.[1] During the ten years preceding the adoption of the Euro, the Croatian economy’s economic cycle was strongly synchronized with that of the Eurozone.

Source: European Central Bank, 2023

A 30 June assessment by the European Commission (EC) on the adoption of the Euro in Croatia indicates that the transition was seamless and effective.[2] The study concludes that the transition preparations occurred according to plan and that the public information campaign co-funded by the Commission provided residents with timely, focused, and succinct information.

Eighty-eight percent of individuals were well-informed about the introduction of the Euro, and sixty-one percent believed the procedure was easy and effective, according to a Eurobarometer study issued one month following the switch.[3]

The two-week period in which both the Kuna and the Euro were in circulation proceeded without incident. The need to publish prices in both Kuna and Euro began on 5 September 2022 and will conclude on 31 December 2023. In addition, starting September 2022, the Croatian government has continuously monitored the prices of 103 predefined and commonly purchased consumer goods and services in nine Croatian cities.

Consequences on prices

It was natural for the public to be concerned about the potential impact of the transition on pricing, especially in an era of rising inflation.[4],[5] The Croatian government, however, took all necessary measures to avoid abusive practices, and the impact of unjustified price rises on aggregate inflation appears to have been quite minimal and broadly consistent with what has been observed throughout prior transitions. In the first two weeks of Euro usage, inspectors fined businesses a total of €234,000 for unjustified price increases. In addition, the government limited the prices of eight vital products, ranging from sugar to chicken.

On 16 August 2022, the “Business Code of Ethics for the Introduction of the Euro” was introduced. In order to provide a secure environment for customers during a dependable and transparent introduction of the Euro, it outlines the norms of ethical behaviour. It attempts to guarantee pricing stability for goods and services by assisting companies in recalculating and displaying prices accurately and without unjustifiable increases. Its seven principles also contain essential parts of the practical preparations, such as the accurate conversion of prices and other monetary values, the display of a set conversion rate, and the education and training of staff on the method for introducing the Euro.

The Code encourages firms to pledge not to exploit the transition for their personal gain, to adhere to the standards governing the transition, and to give clients with the appropriate help. It is modelled after the successful volunteer activities utilized during past transitions. Businesses that join the initiative obtain the right to display the Code’s visual identification label at the points of sale, at the locations where services are provided, and on websites, as well as during marketing and promotional activities such as printed leaflets and catalogues, online advertising and social media marketing, mobile and other media. The badge indicates to consumers that prices have been accurately determined and that businesses are trustworthy. In cases where the principles are not adhered to, the permission to show the label will be cancelled. Over 80% of Croatian shops adopted the code of conduct to ensure proper dual pricing of items.[6]

Addressing the general public preoccupation on price spikes derived from the Euro adoption, Governor of the Croatian National Bank Boris Vujčić said to the Financial Times:[7] “We can now say with confidence that the impact of the Euro introduction was not significant on prices.”

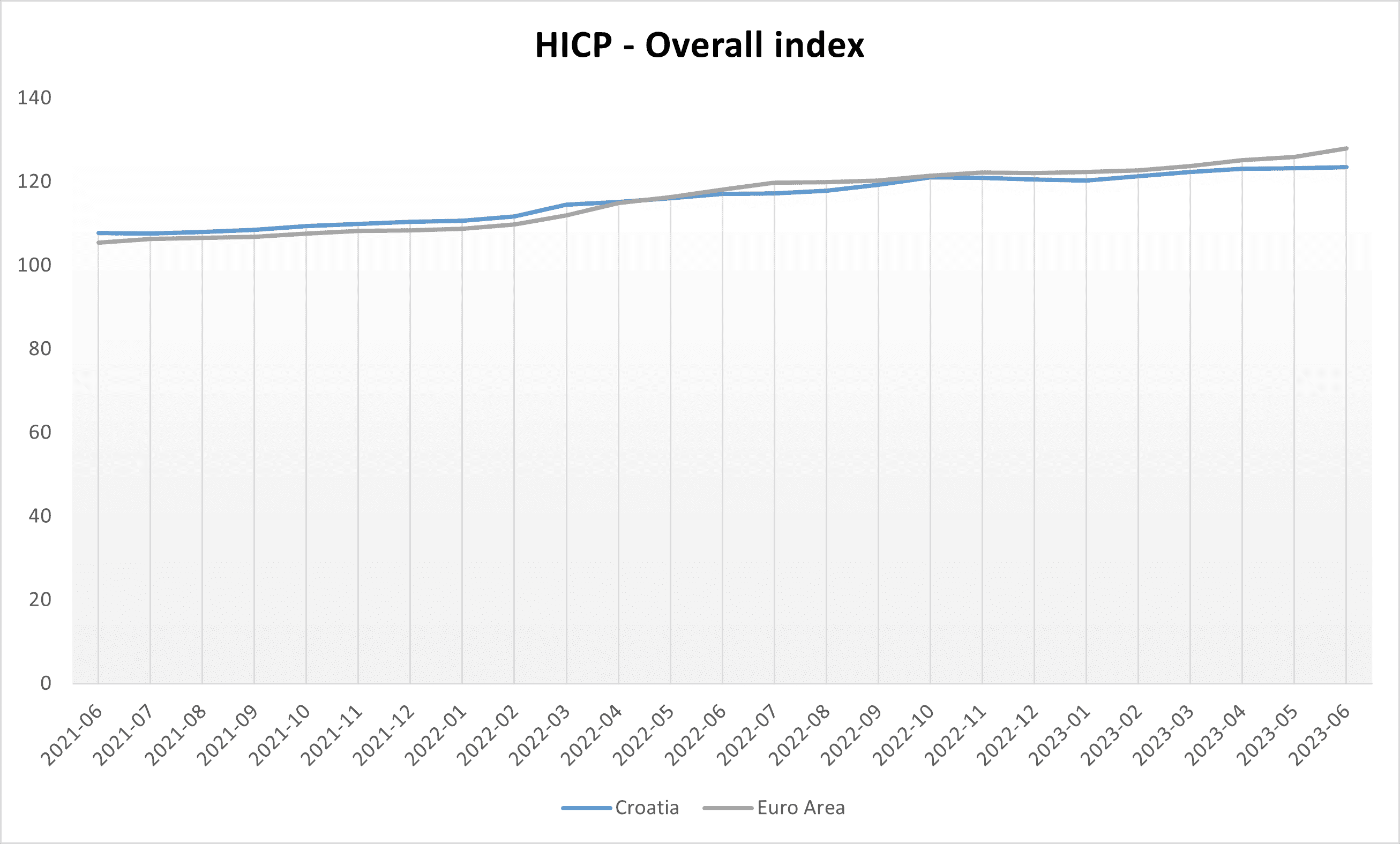

As shown in the chart below, the Croatian HICP (Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices) overall index continued its growth trend alongside the Euro Area one with minor variations, indicating a strong correlation between the Croatian economy and its European partners even before the implementation of the single currency. Notably, after the Euro adoption, the negative difference from the European average increased. This can also be explained looking at the HICP annual rate of change.

Source: Eurostat, 2023

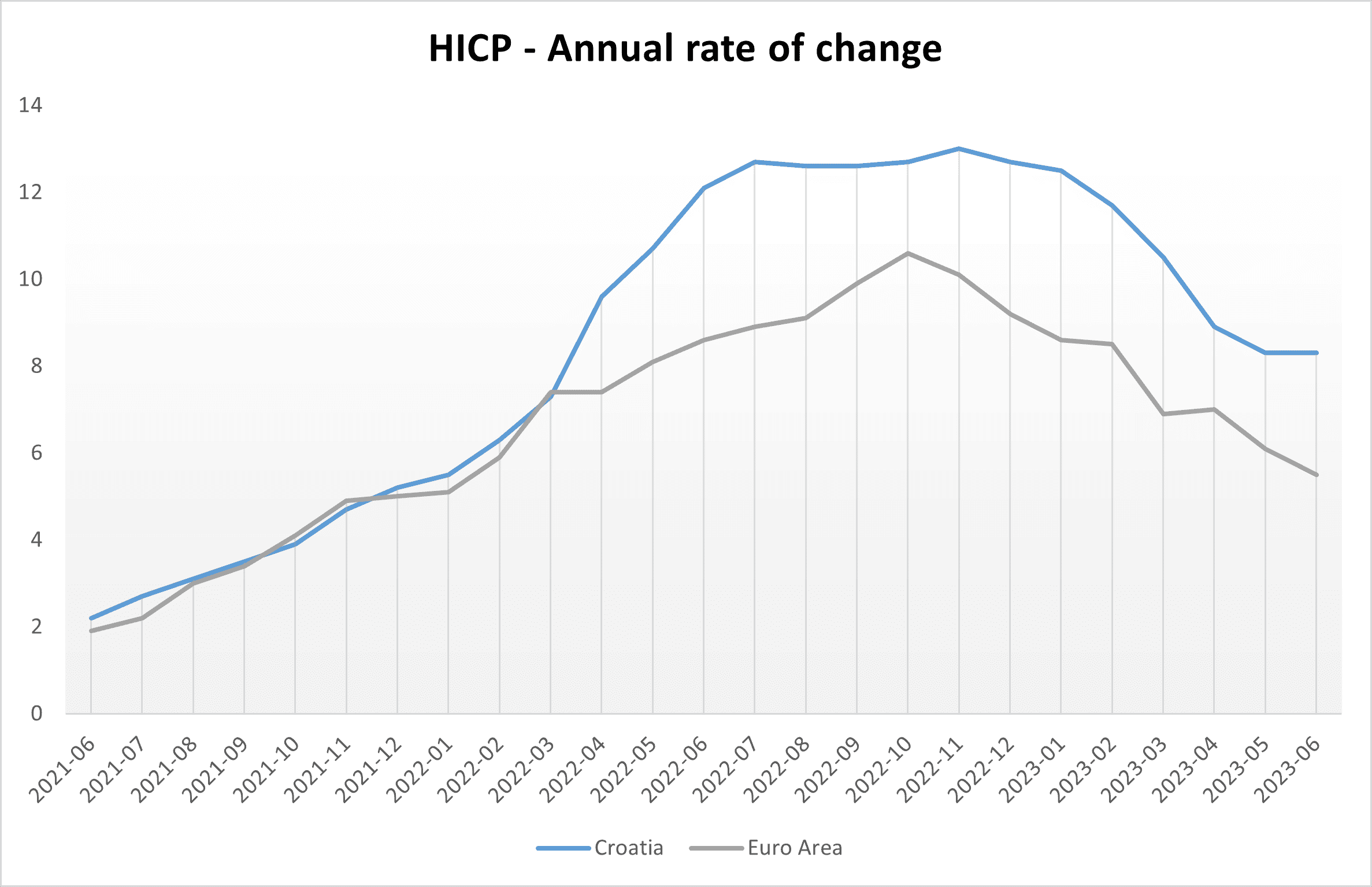

Based on a preliminary evaluation of the available information, Falagiarda et al.[8] noted that the impact of unjustifiable price rises on aggregate inflation appears to have been very minor and in accordance with what was observed during past transitions. The subcategories of products and services that were most affected by price rises in past transitions had the largest monthly price increases on record. Nevertheless, due to the relatively modest weight of the most impacted categories and the fact that the other subcategories were not as affected, the total monthly increase in service costs was restrained. According to the chart below, the monthly HICP annual rate of change in Croatia in January was 12.5 percent and in June it slowed to 8.3 percent. This indicates that the effect of the unjustified price hikes was likely restricted to the month of January and that the Euro is helping Croatia to mitigate its precedent import-related inflationary spikes.

Source: Eurostat, 2023

Despite a more severe inflationary environment, the impact of the Euro transition on consumer prices in Croatia has thus far been very minimal and of the same size as that recorded following previous currency transitions.[9] The incoming data will for a more exact evaluation of the pricing impact of the transition, including its distributional elements. Continuous monitoring is required. Croatia’s experience is a significant lesson for other EU Member States adopting the Euro, since it indicates that the economic costs deriving from the effect of the changeover on inflation are limited and of a one-off character.

Effects of the Euro changeover at the geopolitical level

The geopolitical significance of Croatia’s entry into the Eurozone transcends its macroeconomic relevance. From a historical perspective, Croatia has continually pursued the defining of its identity. As a frontier frontline between the Austrian and Ottoman empires throughout modern history, the catholic Balkan nation was highly impacted by the dynamics of imperial competition and suffered from a longing for self-determination that could never really materialize until the Second World War. As a member of the Yugoslav monarchy founded by Belgrade after World War I, Croatia felt underrepresented and marginalized. However, the first breakup of Yugoslavia in 1941 provided the chance to defeat Serbian supremacy and establish Greater Croatia led by Ante Pavelić. Nonetheless, the war’s conclusion reaffirmed the existence of a Yugoslav state in which Croatia was only a federated entity.

Not until 1991 was Croatia able to reclaim its freedom, viewing Europe as its natural place of belonging. Since the dissolution of Yugoslavia, Croatia has endeavoured to “Europeanise” itself through deeper forms of integration with the European Community, with the support of key European countries that have had significant historical ties with Zagreb, such as Germany, Austria, Italy, and the Vatican – all staunch recognizers of Croatian independence and sovereignty since 1992. In this context, Croatia’s “Europeanisation” has been inversely proportionated to its separation from Serbia and the Yugoslav heritage.

Geopolitically, the accession of Croatia to the Euro Zone and Schengen Area – in conjunction with its 2009 accession to NATO – underlines Zagreb’s resolve to belong to the Euro-American West and to distance itself from its Yugoslav history, particularly with Serbia and its relations with Russia.

The thirty-year Euro-Atlanticist transition in Croatia, which began with the country’s recognition by the majority of Western nations, is now complete. Certainly, Croatia’s European integration has enormous ramifications in the context of the EU and Russia’s geopolitical competition in the Balkans. The geopolitical significance of Croatia’s “turn to the west” is a reduction in Russian influence in the Western Balkans and an increase in German and, to a lesser extent, Italian strategic penetration in the area.[10] While the role of regional actors such as Russia and Turkey is growing in the Western Balkans – in Serbia, and in Albania and Kosovo, respectively – so is the role of European nations with a history of strong ties to the Balkan-Danubian region, such as Germany, Austria, and Italy. Regional tactics influenced by Russia, Turkey, and, more recently, China are impediments to the integration of the Western Balkans, which is now being driven by the West. Moscow, Ankara, and Beijing are the principal actors today challenging Brussels and Washington’s hegemony in the Balkans.

In addition to competing geopolitical counterinitiatives, the relatively prevalent Euroscepticism might have impeded Croatia’s European inclusion. However, Croatian Euroscepticism, which ultimately centres around economic concerns rather than political or ideological issues, is prevalent among just a small portion of the public, with party officials and political elites exhibiting essentially no Euroscepticism.[11]

Moreover, in contrast to other Balkan nations such as Serbia, Croatia appears to have overcome its Eurosceptic inclinations via a constant commitment to Western-inspired projects, such as the pro-Euro-Atlanticist Three Seas Initiative (TSI), whose inaugural summit was held in Dubrovnik in 2016. In general, Croatia has been better equipped to converge to the EU’s acquis than Serbia due to its less constricted internal political arena, its little reliance on regional powers’ meddling in its politics and economy, and the EU’s more consistent enlargement approach.[12]

References

- https://www.ecb.Europa.eu/pub/economic-bulletin/focus/2023/html/ecb.ebbox202208_02~15fd36600a.en.html#:~:text=On%201%20January%202023%20Croatia,since%20Lithuania%20joined%20in%202015. ↑

- https://economy-finance.ec.Europa.eu/system/files/2023-06/COM_2023_341_1_EN_ACT_part1_v4.pdf ↑

- https://Europa.eu/Eurobarometer/surveys/detail/3013 ↑

- https://www.express.co.uk/news/world/1724015/croatia-Euro-Eurozone-schengen-European-union-ivan-sincic-mep ↑

- https://www.euractiv.com/section/economy-jobs/news/croatia-clashes-with-merchants-over-post-Euro-wild-price-hikes/ ↑

- https://economy-finance.ec.Europa.eu/system/files/2023-06/COM_2023_341_1_EN_ACT_part1_v4.pdf ↑

- https://www.ft.com/content/6e3b5bee-a953-45ed-a91a-75c0c1dfaada ↑

- https://www.ecb.Europa.eu/press/blog/date/2023/html/ecb.blog.230307~1669dec988.en.html ↑

- https://www.ecb.Europa.eu/press/blog/date/2023/html/ecb.blog.230307~1669dec988.en.html ↑

- https://www.colEurope.eu/sites/default/files/research-paper/edp_6-2020_heemskerk_0.pdf ↑

- https://ecfr.eu/article/commentary_wall_in_the_Eurosceptic_challenge_in_croatia/ ↑

- https://www.colEurope.eu/sites/default/files/research-paper/edp_6-2020_heemskerk_0.pdf ↑