Jakov Milatovic is the new president of Montenegro. In the run-off against the outgoing Milo Djukanovic, Milatovic – the candidate of the centrist “Evropa sad!” (Europe Now!) movement – won a landslide victory with over 60% of the vote, confirming the predictions made after the first round, when the 36-year-old Milatovic won 29% of the vote to Djukanovic’s 36%. Voter turnout was over 70%, confirming that Montenegro is unique in the Balkans in terms of voter participation.

Although the presidency in Montenegro has no executive function, April 2’s vote marks a historic turning point for the Balkan peninsula’s least populous country. Djukanovic had been in power as president or prime minister for 32 years, making him Europe’s longest-serving leader. It was a defeat that had been ripening since August 2020, when his Democratic Party of Socialists (DPS) lost the parliamentary elections for the first time. Since then, two leaders have changed in Podgorica, creating a climate of instability and political fragmentation. This vote is therefore important in view of the upcoming parliamentary renewal. Indeed, Montenegrins will be called to the polls again on 11 June, when the movements and citizens who supported Milatovic will be able to confirm the change of political course and the departure from the scene of the man who, until now, was the undisputed leader of the country.

The election campaigns of the two opponents were tailored to each candidate’s target groups, with Jakov Milatovic having to perform the greater balancing act. His electorate ultimately consisted of three very different groups: pro-European voters, the country’s many pro-Serb forces and, finally, protest voters of all ages and ethnicities who wanted to put an end to what they saw as the corrupt “Djukanovic system”. Accordingly, Milatovic sought to increase the overlap of this group, and he succeeded.

The pro-Serbian parties now approve of the country’s European orientation, while Montenegro’s pro-European voters have accepted a state treaty signed years ago with the Serbian Orthodox Church. In addition, Milatovic has vowed to step up the fight against corruption, which is likely to affect the upper echelons of the police and judiciary. They have regularly been accused of links to criminal organisations, leading in some cases to arrests within the court. Milatovic’s campaign was based on the overcoming of ethnic tensions, a clear pro-European course with the implementation of all necessary reforms, the strengthening of the rule of law and economic measures to maintain living standards.

Djukanovic, on the other hand, tried to present himself as the “civic candidate”, but in terms of substance he ran a fear campaign: he painted on the wall the risk of a “return to the Middle Ages”, with Montenegro being annexed as part of Greater Serbia in the event of his failure. These backward-looking statements only reached his core base, but left swing voters with the feeling that he was more interested in separating Serbs and Montenegrins than in unifying them. In any case, the idea of compensating for Milatovic’s enormous advantage in the country’s few significant cities did not work.

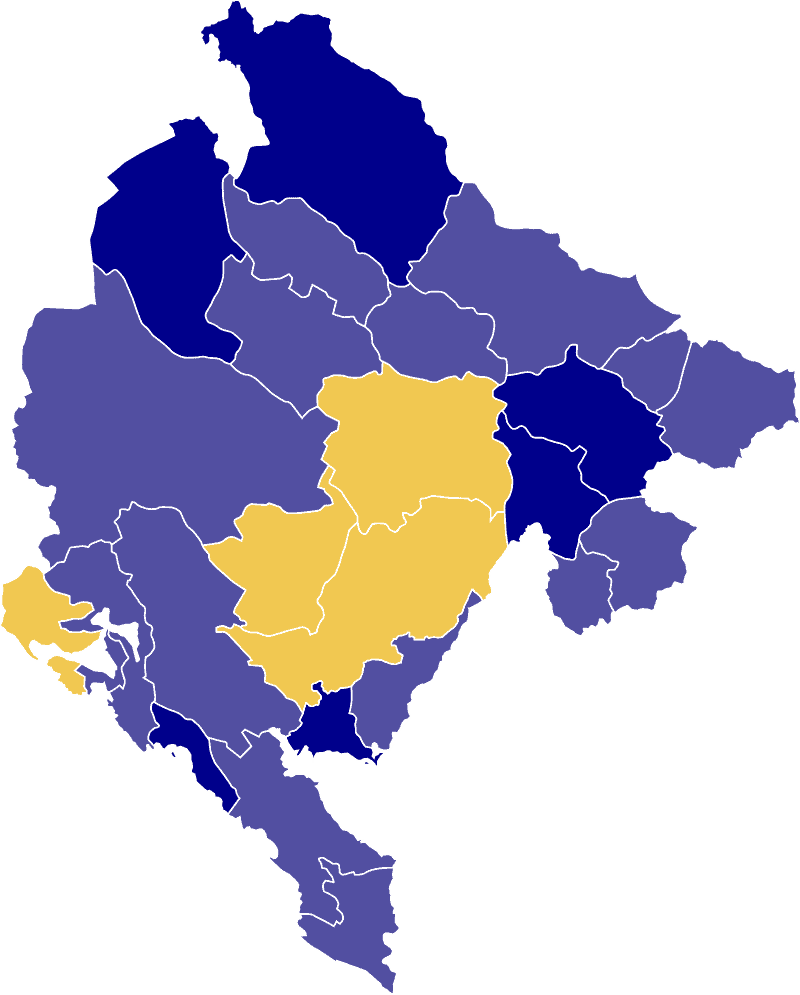

First round results by municipality (Mandic: Dark Blue, Milatovic: Yellow, Dukanovic: Violet)

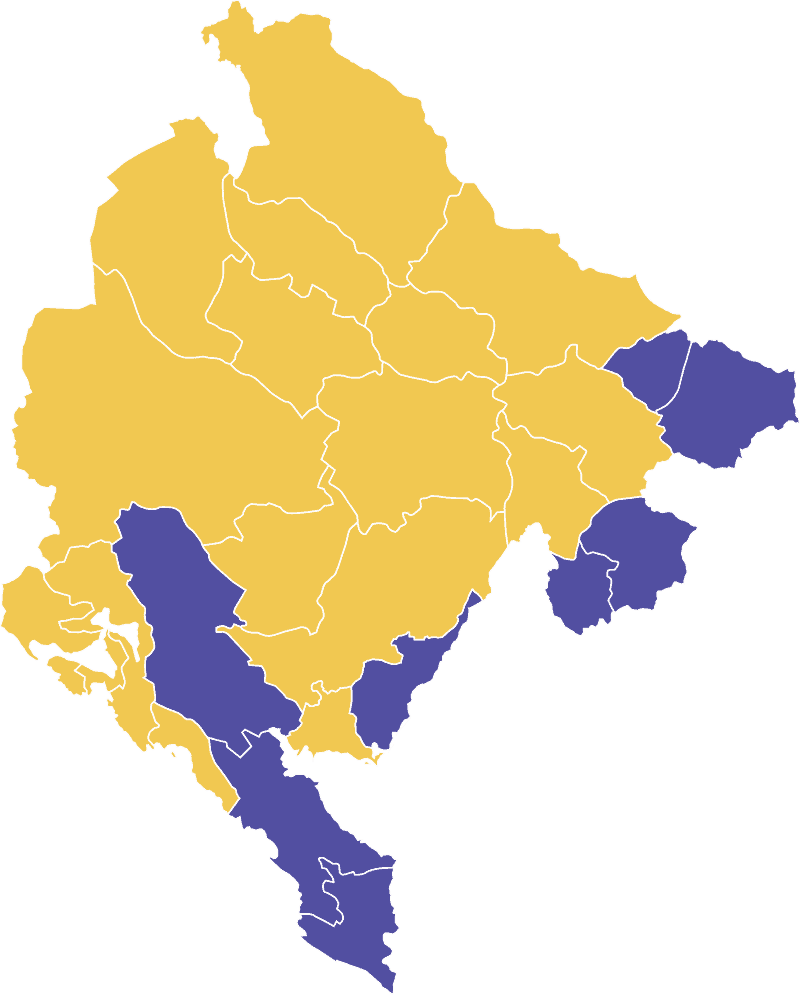

Second round results by municipality (Milatovic: Yellow, Djukanovic: Violet)

A new political scenario for Montenegro

Born in Podgorica 36 years ago, Jakov Milatovic is an economist who will be the first non-DPS leader to serve as Minister of Economic Development between the end of 2020 and April 2022. Milatovic has an international academic background, having spent time studying in Illinois (USA), Vienna and the Sapienza University of Rome, while his Master’s degree was obtained in Oxford. Despite his young age, Milatovic has several professional experiences that have contributed to making him an economist with a solid knowledge of international finance: he has worked in the banking sector in Montenegro and Germany, and since 2014 at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, where he was responsible for the countries of Central and Eastern Europe and the Balkans. Before becoming Minister in 2020, he gained further international experience, including at the Montenegrin Embassy in Rome.

In June last year, together with Milojko Spajic, former finance minister between 2020 and 2022, he founded the Europe Now! movement, which achieved its first electoral success in the Podgorica municipal elections last October, ousting Djukanovic’s DPS along with other opposition parties. Although in the run-off Europe Now! won the votes of pro-Serbian nationalists who had supported other candidates in the first round, the movement appears to be transcending the two nationalist ideologies that have polarised the country in recent years: the more conservative and pro-Serbian one, and Djukanovic’s Euro-Atlanticist Montenegrin one. Milatovic’s programme promotes a pro-European agenda based on respect for the rule of law and a series of economic reforms, including the tax system, the introduction of progressive brackets and an increase in the minimum wage.

For Milo Djukanovic, this was the worst defeat of his long political career. His government had lasted for 32 years, apart from three brief interruptions when the leader voluntarily withdrew from political life, and had accompanied all the country’s institutional successions.

In 1991, at the age of 29, he became prime minister when Montenegro was still part of the moribund socialist Yugoslavia; his mandate was then renewed – again with the approval of Slobodan Milosevic – when the federation was limited to Serbia and Montenegro. Djukanovic was president for the first time between 1998 and 2002, while in all the subsequent legislatures – after Montenegro became independent from Belgrade by referendum in 2006 – he always held the role of prime minister, with three interruptions: in 2006, 2010 and 2016, the day after the last parliamentary vote that consecrated the overwhelming power of his DPS. In 2018, Djukanovic ran for president and won the election in the first round. But in these five years, Milo’s power has lost the support of around 70,000 votes, or 13% of the electorate.

Why? More than the rampant corruption and dubious business deals that enriched Djukanovic – including a cigarette deal with Apulia that the Italian authorities eventually rejected – the ‘original sin’ that cost the outgoing president electoral support was the ‘Law on Religious Freedom’ of late 2009. Among other things, the law stipulated that religious property owned by the state up to 1918, when Montenegro was incorporated into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, and which had not subsequently been legally adapted, would revert to state ownership. In fact, the law was perceived as a direct attack on the Serbian Orthodox Church – which exercises its power in Montenegro through the Metropolitan – which responded by mobilising thousands of believers in mass protests that soon gained enormous political weight against the President and the DPS. Indeed, the clash has reignited Montenegro’s identity issue, as some 30% of Montenegrins identify as Serbian, but more than 70% of the population is Orthodox (and the vast majority identify with the Serbian Orthodox Church, rather than the autocephalous Montenegrin Orthodox Church).

Djukanovic, for his part, has also ridden on identity issues, promoting a clear political and cultural distinction from Serbia since independence and generating a Montenegrin nationalism that has come to coincide with the political pillars of his leadership. In the summer of 2020, pro-Serbian parties were thus able to capitalise on the discontent generated by the law on religion by attracting new voters and isolating Djukanovic politically.

What is to be expected for the future?

Despite open authoritarianism – which has made Montenegro the first “stabilitocracy” in the region – and a well-established patronage system, Djukanovic has over the years cultivated political and cultural demands of a progressive nature, especially by the standards of neighbouring countries, such as the recognition of same-sex unions. In addition, under his leadership, Montenegro has continued to publicly pay attention to the inclusion of minorities living in the country, especially Albanians and Bosnians. Over the years, therefore, opposition to Djukanovic has developed along two sometimes overlapping vectors, especially on anti-Western positions: conservatism and pro-Serb nationalism.

It is therefore not surprising that the poll result’s celebrations in the streets of Podgorica were marked by Serbian flags and nationalist songs about Kosovo. Although Milatovic also enjoyed the electoral support of the nationalists, a change of course in the country’s foreign policy is out of the question.

Montenegro, a NATO member since 2017 and an EU candidate, will face major challenges with the government that will emerge after the June parliamentary elections, when the current political and national polarisation is likely to be consolidated. Djukanovic may be on his way out, but his party still has a relative majority of votes and can be expected to fight on all the issues that the country’s ruler father claimed as his political achievements.

However, it is not entirely likely that the parliamentary elections called by Mr Djukanovic will take place on 11 June. First, the Constitutional Court has not yet clarified whether the president can dissolve the legislature without its consent. If the court rules against it, parliamentary elections would have to be held by August 2024 at the latest. It is ironic that Djukanovic’s DPS party and the pro-Serb Democratic Front (DF) – two parties with radically opposite political orientations – both fear early elections.

The DPS is afraid of its own electorate’s disinterest and of entering the contest as a losing party. The pro-Serb DF, which currently holds a third of the seats in parliament, can only hope for a repeat of its performance in the first round of the presidential election, when its leader, Andrija Mandi, won just 19 per cent of the vote. The party faces significant losses in the upcoming parliamentary elections, as the “Europe Now!” movement is expected to benefit from Milatovic’s recent victory.

Polls show that five out of six Montenegrins see their future in the EU, and to achieve membership a large and reform-minded parliamentary majority is needed. This will be extremely difficult without the support of pro-Serbian parties. Milatovic’s victory in the presidential elections has put him in a good position to negotiate a workable solution with the traditionally pro-Serbian parties.