People take part in a protest against the presidential election results demanding the resignation of Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko and the release of political prisoners, in Minsk, Belarus August 16, 2020. REUTERS/Vasily Fedosenko

By Corentin PARISOT – Original in FRENCH HERE – Also available in Polish Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 – Full Document

The events in Belarus in recent days have led to violent repression of demonstrations by the ruling government and the exile of the opposition leader in Lithuania. Following the publication of the results of the presidential election of 9 August, a wave of protests has been sweeping across the country, marking a clear break between part of the population and the ruling power. A number of international bodies also denounced the conduct of the elections. But is this political crisis a fortuitous event linked to the election or is it indicative of deeper popular discontent? Is this crisis organic? Are the reaction of the ruling power and its choice to severely repress demonstrations the symptoms of a regime that feels shaky or, on the contrary, a demonstration of strength by a ruling power determined to hold on? What answers could Lukashenko decide to give? What are the most likely scenarios for this crisis and how will the balance between the actors be altered as a result? Is there a risk of a weakening of the Belarusian state that could lead to the establishment of a hotbed of instability at the gates of Europe? What would be the consequences for Belarus’ neighbouring countries and trading partners? And how could the geostrategic balance in Europe be affected? The political crisis in Belarus is central to Blue Europe’s concerns. Whatever the outcome, Central and Eastern Europe will be deeply affected. This crisis is taking place in a tense social, economic and international context. We propose to analyse it in all these dimensions and to follow it up on a regular basis. This article in particular, the first in the series, aims to enlighten our readers on the situation of this little-known Eastern European country in Western Europe.

Belarus is an Eastern European state, the power has been in the hands of Alexander Lukashenko since 1994. The latter is frequently accused of authoritarian practices: the 2019 ranking of countries according to their democracy index gives Belarus an index of 3.13 on a scale of 10, placing it among authoritarian regimes. Despite his dictatorial practice of power, Lukashenko has long enjoyed strong popular support, not least thanks to a social policy that is genuinely oriented towards the people. Indeed, the country is among the least unequal in the OECD (In 2016 the Gini index of Belarus was 0.27, against 0.32 – Source OECD 2019). However, the economic crisis, poor management of the economic consequences of the coronavirus, and above all endemic and growing corruption have shaken the support enjoyed by the Belarusian President, and allowed opposition forces to emerge: the country is currently facing the biggest demonstrations since the 1990s and the fall of the USSR. Part of the Belarusian population does not accept the results of the presidential election of 9 August. The elections were probably rigged. Lukashenko was re-elected in the first round with 80.08% of the votes cast, while his main opponent, Svetlana Tsikhanovskaya was credited with 10.09% of the votes. The turnout was 84.27% of those registered. It is impossible to say at this stage whether Lukashenko won the elections or not: it can be said with very little doubt that the elections were indeed rigged. The opposition has denounced the massive fraud and is contesting the results. Tsikhanovskaya claims victory and calls on Lukashenko to relinquish power. However, for fear of pressure and in the face of the risks in Belarus, Tsikhanovskaya has fled to Lithuania. Similarly, however, it can be said that Tsikhanovskaya did probably not win the elections. Lukashenko’s rival stands out for the atypical aspect of her candidacy: initially not a candidate, she took over from her husband, Sergei Tsikhanovsky, a blogger who has been imprisoned since the 29th of May. Several other candidates have also been imprisoned. The Belarusian intelligence services have not changed their methods since the fall of the USSR: using brutal methods, Belarus is not improving its international standing.

In order to understand the situation in Belarus, a brief portrait of the country and its very close ties with Russia should be drawn up. A strong feeling of closeness to the Russians is at least partially shared by the population, due to the historical ties between the two countries, Belarus having long been an integral part of Russia. The territory of Belarus corresponds to the former “White Russia”. Culturally and linguistically, Russian is the usual language of 70% of the population, Belarusian being the main language of only 23% of the population – only 29% of Belarusians can speak, read and write Belarusian. Economically, Belarus is heavily dependent on Russia, 47% of trade is with the latter. (source WTO 2019) Some sectors, such as meat production or tractors (very large Belarusian production), have only Russia as their sole outlet. Moreover, the country is totally dependent on Russia for its energy supplies: it buys its oil at a price well below world prices, with Russia using its energy resources as a tool of influence. However, it should be noted that a first delivery of American oil was made to Belarus in mid-May. This is still only a drop in Belarusian energy consumption, but the development of the region’s oil and gas infrastructure, in the framework of the Three Seas Initiative, could eventually allow Belarus to diversify its supply. These elements promote rapprochement between the two countries, so much so that a project to unify the two countries is progressing. In 1999 the Treaty on the Establishment of the Union of Russia and Belarus was signed. At the end of the integration process the two countries should form a single entity. The process has stagnated or even regressed with the end of the customs union in 2001. It was relaunched by Russia in 2019, almost unilaterally. The Kremlin plans a fiscal, customs and energy union by 2021. However, Lukashenko was not very favourable, seeing the loss of control over his country in a negative light. Belarus and its leader are therefore in a difficult situation, its close ties with Russia and its lack of openness to Europe do not allow it to manoeuvre internationally. Moreover, the European authorities are not inviting it to move closer together, putting half of its administration on the list of persons banned from trading in the European Union. Lukashenko and some thirty officials were banned from obtaining visas by the European Union in 2006. Moreover, Russia has powerful means of pressure to force the hand of the Belarusian leader: Belarus benefits from significant discounts on the price of oil and gas, of the order of 30%. More generally, the Belarusian economy is poorly integrated into world markets, and is only really open to the Russian market. Moreover, Belarus was not affected by the 2008 crisis, but entered into recession in 2015, following the economic sanctions against Russia.

The revival of the process of integration of Belarus and Russia into a single entity has led to a cooling of Russian-Belarusian relations. Lukashenko accuses Russia of interference in his country’s affairs. These accusations culminated on 29 July with the arrest of 33 Russians, presented as fighters of the Russian paramilitary company Wagner. Minsk accused them of fomenting terrorist acts with Belarusian opponents with a view to destabilising the country on the eve of the presidential elections on 9 August. Despite the cooling of relations, Vladimir Putin was the first head of state to congratulate Lukashenko on his re-election, even before the final results were published. Despite attempts at Russian interference in Belarusian internal affairs, it would appear that Lukashenko is turning his attention to Russia. The Belarusian President rejected the offer of mediation made by Poland and the Baltic countries and spoke on Saturday 15 August with Vladimir Putin in order to obtain his support. He spoke of an attempt at a ‘revolution of colour’ in his country. The results of the election gave rise to a major popular protest, although reported to the country size, they are minimal. Belarusians are not fond of demonstrations, yet thousands of people took to the streets of the country to demonstrate their hostility to the regime, demanding new elections and the departure of Lukashenko (around 100,000 according to the majority of the media, Russian and Western alike). Police repression was particularly fierce with more than 7,000 arrests, hundreds of injured and two dead. At the same time, the protests were growing in size, with 100,000 people demonstrating in the centre of Minsk on Sunday 16 August (about half of them in the end). The Belarusian government can only have limited confidence in its security forces. The police is not sufficient and the government has mobilized the army: the latter is a conscription army, by nature much less reliable than a professional army. Many scenes of fraternisation took place between the demonstrators and the forces of law and order. Police officers filmed themselves throwing their uniforms in the trash, unable to bring themselves to support the regime. It is to be feared that Russia is interfering more actively in Belarusian internal affairs, the presence of Russian soldiers in Belarus has been reported. These soldiers use the same modus operandi used in the Crimea in 2014, namely hooded soldiers without flags or distinctive insignia, travelling in vehicles without licence plates. Numerous convoys of unmarked military vehicles have been reported in Russia, heading towards Belarus.

The current crisis could be seen as a revolution of colour, anti-Russian and pro-European. It is not. Belarusians and Russians have a sense of a common identity, and there is no hostility towards Russia in Belarus. Thus, drawing a parallel with the case of Ukraine appears to be irrelevant. The Ukrainian case is peculiar, with the west of Ukraine looking to the west while the east (Donbass and Crimea) is pro-Russian. This East-West opposition has its roots in the history of the country. The east is predominantly populated by Russian speakers, many of whom consider themselves more Russian than Ukrainian in terms of identity. Ukraine is a country agitated by irredentist or at least regionalist demands. Belarus, on the other hand, is homogeneous in terms of the composition of its population with few dividing lines. It is also irrelevant to speak of one side against the government, because there are two opposition camps. We will come back to these differences in the second article. Another explanation factor that naturally comes to mind would be an opposition between a pro-European and anti-Russian urban middle class against a conservative and pro-Russian working class. Again, this is not the case here. The wave of protest is uniting all classes of Belarusian society, from the workers in state-owned factories, traditional supporters of the regime, to the country’s ruling elites, including of course the middle class. In this respect, it is very important to point out that two members of the system ran for the presidential elections against Lukashenko: Viktor Babariko is in charge of the board of directors of Belgazprombank, until now the Belarusian business community has been kept out of political life; Valery Tsepkalo is a former diplomat and has been ambassador to the United States. The wave of protests in Belarus is therefore essentially directed against the person and practice of Lukashenko’s power. Lukashenko has long enjoyed broad popular support, but in recent years it has completely collapsed under the influence of multiple factors. Since the economic crisis of the mid-2010, Belarus has seen a deterioration in living conditions. Corruption is undermining the country, whereas in the 1990s Lukashenko had made the fight against corruption one of his main concerns. Corruption has finally come back with a vengeance. In addition to all these factors, the coronavirus crisis can be seen as a catalyst for popular anger. The management of the coronavirus crisis has weighed heavily on Lukashenko’s popularity, as he mocked the sick by claiming that a glass of vodka is enough to prevent the disease. The relative popularity of the main opponent Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, totally unknown a few months ago, can therefore be explained by a rejection of Lukashenko. Her candidacy received the support of all the regime’s opponents. Her programme is moreover vague, mainly centred on the fight against corruption and the desire to put an end to the reign of the “last dictator of Europe”.

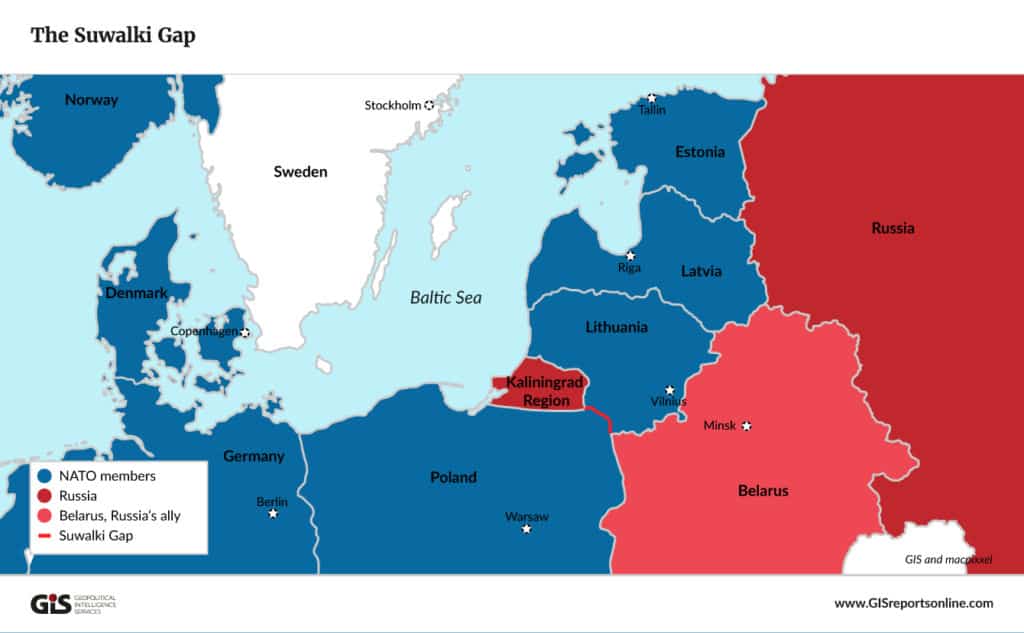

PNo matter who wins for Russia, Lukashenko and the majority of the opposition are pro-Russian. A scenario in which Belarus would move away from Russia and open up to Europe seems unlikely. Lukashenko will not be able to stay in power without Russian support; if he uses foreign troops to intensify repression, his popularity will be permanently buried. The European Union and the United States will certainly react with economic sanctions, which will make Belarus even more dependent on Russia than it already is. In this eventuality, Lukashenko will no longer be able to oppose the planned union of Russia and Belarus, and the decade 2020 would then see the annexation of Belarus by Russia. The geostrategic consequences would be significant. Ukraine would find itself surrounded by Russia. The situation would also become critical for the Baltic States, which would find themselves virtually cut off from the rest of Europe, with the distance between the exclave of Kaliningrad and Russia being only about 60 kilometres. This thin strip of land providing territorial continuity between NATO members is known as the Suwalki Gap and is of vital strategic importance. If the Russians manage to take control of it, NATO would not be able to rescue the Baltic countries in the event of Russian aggression.

In addition to the immediate threat to the Baltic States, Ukraine and Poland, the whole of Europe could be destabilised. Russia would prove once again that it is possible to act against international law. A retreat by NATO and Europe on the annexation of Belarus could eventually lead to a desire to annex the Baltic countries, Ukraine and Moldova. A part of the Russian ruling elite has retained nostalgia for the Soviet Empire and many Russians dream of restoring Russian power. Should Lukashenko be forced to hand over power to Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, Russia would not lose out. It offers no serious alternative, its programme being limited to fighting corruption and putting an end to the reign of the autocrat. The entire opposition has rallied under its banner, but once elected it would not have a consistent majority. All the deputies of the Belarusian lower house support the ruling power. The Belarusian constitution authorises the President of the Republic to dissolve parliament and call new parliamentary elections. In this scenario it seems likely that the anti-Lukashenko coalition would break up, united only by opposition to one man and not around a programme. Moreover, the Russians have considerable influence over Belarusian society, the Russian media being widely used by the Belarusians. The Kremlin could therefore use its influence to favour the candidates most compatible with its plans, as no candidate is opposed to Russia in any case.

In addition to the immediate threat to the Baltic States, Ukraine and Poland, the whole of Europe could be destabilised. Russia would prove once again that it is possible to act against international law. A retreat by NATO and Europe on the annexation of Belarus could eventually lead to a desire to annex the Baltic countries, Ukraine and Moldova. A part of the Russian ruling elite has retained nostalgia for the Soviet Empire and many Russians dream of restoring Russian power. Should Lukashenko be forced to hand over power to Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, Russia would not lose out. It offers no serious alternative, its programme being limited to fighting corruption and putting an end to the reign of the autocrat. The entire opposition has rallied under its banner, but once elected it would not have a consistent majority. All the deputies of the Belarusian lower house support the ruling power. The Belarusian constitution authorises the President of the Republic to dissolve parliament and call new parliamentary elections. In this scenario it seems likely that the anti-Lukashenko coalition would break up, united only by opposition to one man and not around a programme. Moreover, the Russians have considerable influence over Belarusian society, the Russian media being widely used by the Belarusians. The Kremlin could therefore use its influence to favour the candidates most compatible with its plans, as no candidate is opposed to Russia in any case.

MISC https://www.lefigaro.fr/flash-actu/bielorussie-32-combattants-russes-arretes-ont-ete-remis-a-moscou-20200814 https://www.la-croix.com/Monde/Europe/En-Bielorussie-legitimite-regime-Loukachenko-seffrite-2020-06-09-1201098340 https://belarusdigest.com/story/the-state-of-the-union-belarus-russia-and-the-virtual-state/