1. Introduction

The Russian Federation’s February 24, 2022 invasion has shaken up the international political order, becoming the most serious conflict in Europe since the ’90. It is impossible to clearly identify the causes of the war. On the one hand, it may have to do with Russian imperial ambitions, dating back to the 15th century, when the mythological concept of a Third Rome was created after the fall of Byzantium. On the other hand, there are also more down-to-earth, economic reasons. Indeed, at the beginning of the 21st century, there was a change in the trend regarding commodity prices, which had been falling since the First World War. As Asian economies grew richer, demand for global middle-class consumer goods began to reach unprecedented levels, stimulating an increase in commodity prices. In modern economies, the commodities make the bulk of the economy.

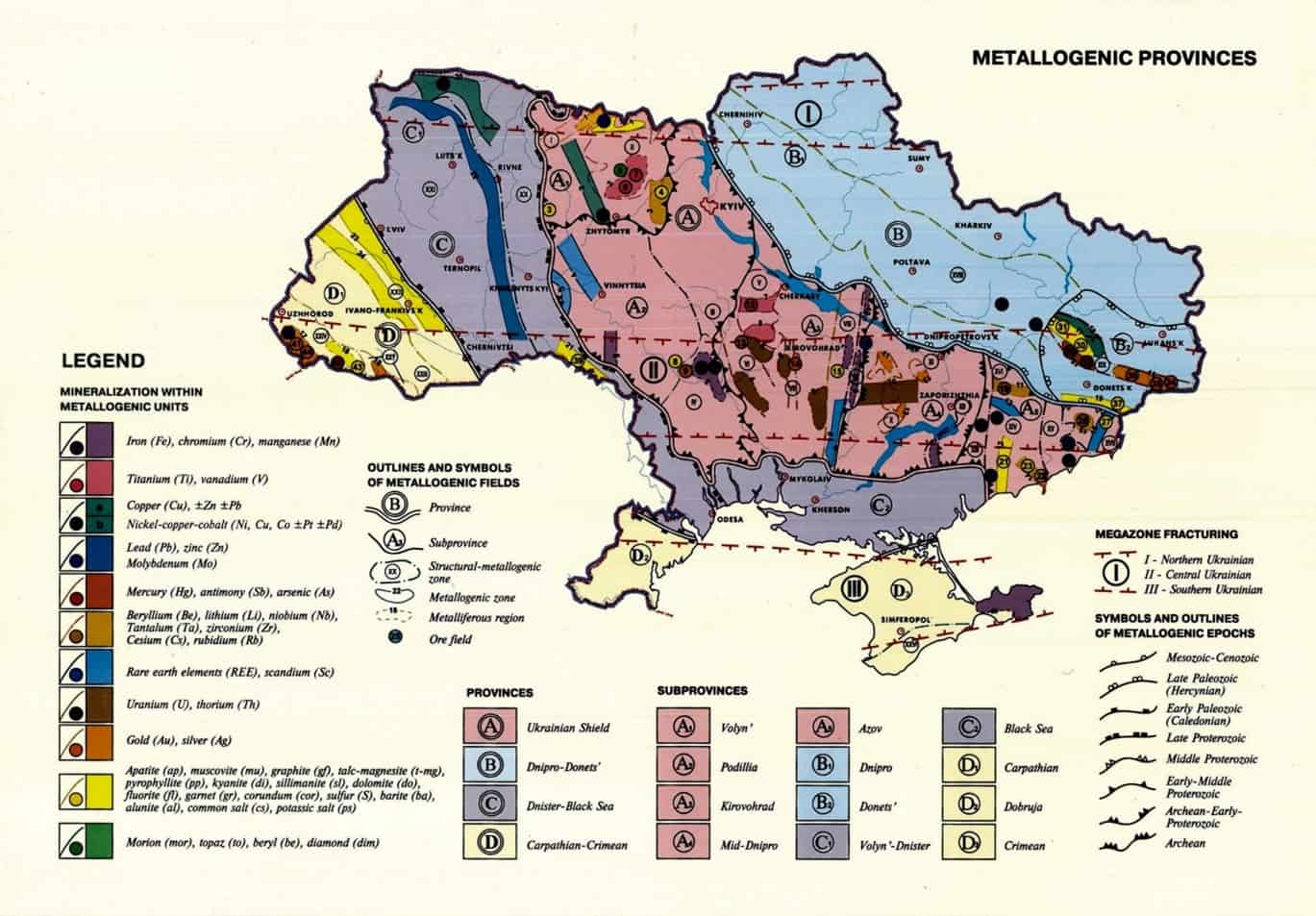

Nowadays, energy raw materials are losing their previous competitive advantage, posing a serious threat to the Russian exports (as Russia hasn’t fully transitioned to a inwards market economy). At the same time, rare earth metals are gaining in importance, finding a multitude of applications in the electronics, energy, aerospace industries and many other new technology sectors. Ukraine has sizable deposits of the aforementioned raw materials, which could reach a total value of as much as $11.5 trillion. Those are still mostly prospects without mining, but that could mean a lot in the long term. The establishment of closer economic cooperation with EU countries and the pursuit of accession after the war could therefore become a huge opportunity for the reconstruction and development of the Ukrainian economy and open a new chapter in the history of independent Ukraine.

2. A conflict for resources

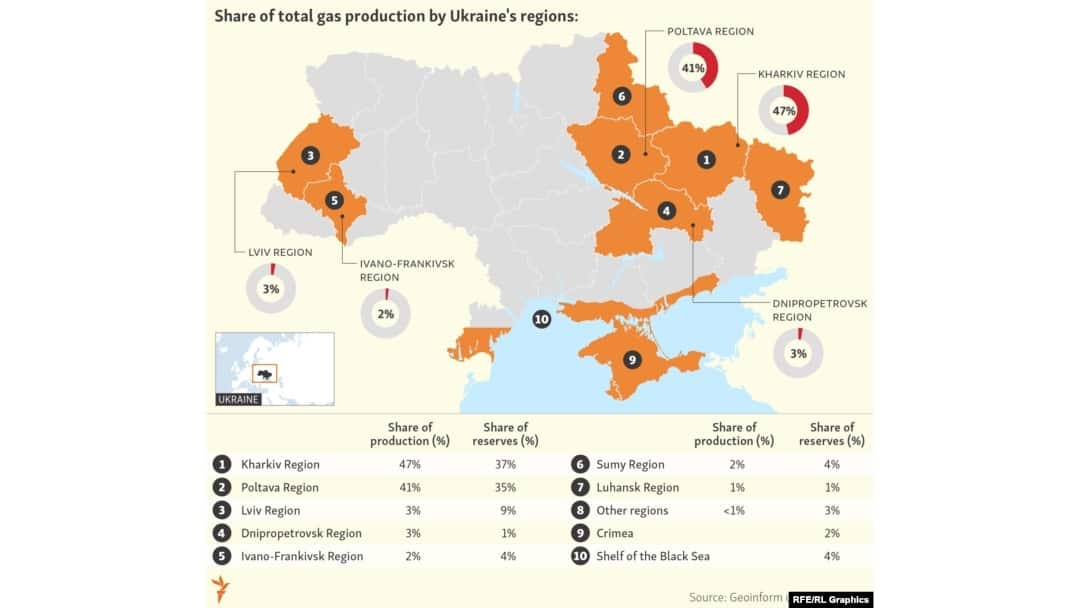

The Donbass region was the scene of fierce fighting between Ukraine’s armed forces and Russian-backed separatists. The site was not a coincidence – as up to 80% of Ukraine’s total oil, natural gas, coal and rare earth deposits are located there. Despite this, Ukraine continued to strive for independence from the Russian energy sector – in 2021, the state-owned Naftogaz was preparing to drill test wells in 32 offshore areas of the Black Sea, but these plans were thwarted by the Russian army invasion launched on February 24, 2022. Thus, it is not difficult to see that an important substrate of the war is competition for raw materials – in 2020, almost 50% of Russian exports went to European countries, which would certainly prefer to source energy resources from pro-Western-oriented Ukraine.

Unlike the annexation of Crimea in 2014, however, this time Western countries are taking steps to support Ukraine, both in the form of military and humanitarian aid (which has already exceeded a total of $100 billion) and sanctions imposed on the Russian Federation – since February Russian foreign exchange reserves have declined by $75 billion, while another $330 billion has been frozen by EU member state banks. A kind of “Copernican coup” in relations with Russia was also announced by Charles Michael, according to whom “topics that are essentially national subjects – energy, defense, economy – will be treated strategically as elements of European sovereignty.”, which is one of the findings of the EU’s Versailles Declaration. This means that with the planned development of renewable energy sources, energy resources are losing their previous competitive advantage. Thus, other resources, especially rare earth metals, are gaining in relative importance.

3. Rare earth deposits as a strategic competitive advantage for Ukraine

Rare earth metals are a group of 17 chemical elements (15 lanthanides, scandium and yttrium) currently used in many high-tech industries, such as the production of lasers, magnets, chips, catalysts, satellite technology or advanced communications systems, making them essential for the development of digital economies. The world depends heavily on China for their extraction – in 2021 it accounted for 60% of global production, while the United States mined only 15%. Countries in Asia and Oceania are responsible for the rest, which means that European economies rely solely on imports. Until recently, this was not a problem for the developed economies of the European Union, however, the beginning of the 21st century marked an important turning point. As developed economies shifted production to Asian countries, East Asian countries’ share of global GDP rose from less than 11% in 1970 to 24% in 2019. It has also translated into a significant increase in the wealth of Asian consumers – in 2015 they already accounted for 36% of the world’s middle class spending, but by 2030 their share is expected to rise to as much as 57%. As a result of the significant increase in demand for consumer goods, since 2000 global commodity prices have begun to rise for the first time since the First World War, threatening economies dependent on their imports.

The situation is no different with rare earths – with plans to carry out a green transformation of EU economies by 2050, demand for them could increase up to threefold, which exceeds their current extraction capacity. For this reason, they are called the “bottleneck of digital civilization”. The total value of rare earth deposits found in Ukraine is estimated between $3 trillion and $11.5 trillion Among them are also sizable deposits of lithium, which is the most important element used in “green” technologies like photovoltaics, lithium-ion batteries and ICT infrastructure. In light of the above, they are sufficient to “secure Ukraine’s economic future for the next century”. Thus, they represent a strategic competitive advantage for the Ukrainian economy, capable of supporting the country’s reconstruction and providing unprecedented development prospects after the war.

4. Prospects for Ukraine’s post-war economy

On August 22, 2022, researchers at the Kyiv University of Economics estimated the value of Ukraine’s infrastructure losses to date at $113.5 billion, which will require an outlay of $200 billion to rebuild it to its pre-war condition. Ukraine’s rare earth deposits will also have an extremely important role to play in post-war reconstruction. As mentioned earlier, their total value is estimated to be between $3 trillion and $11.5 trillion, which could change as they are mined due to growing global demand. This means that even taking on the role of a supplier of raw materials to Western countries would enable Ukraine’s GDP to multiply, which was only $200 billion in 2021. However, it should become the goal of Ukraine’s policymakers and economists to lead their economy up the value chains, enabling domestic industry to at least partially exploit rare earth deposits to produce high-technology products like photovoltaic panels, magnets or microchips. Poland’s offered assistance in rebuilding the energy sector, enabling the transfer of the necessary know-how, could prove to be an important support in this regard. Similar signals were already coming from the EU a few months before the war began.

In the context of the above considerations, one of the most important issues in the coming years will also be the question of Ukraine’s potential accession to the European Union. Despite opposition from some countries of the “old union,” in an expression of political support, Ukraine was granted official candidate status in July 2022, marking the first significant landmark in this matter. While the road to becoming a member of the EU may still take many years, candidate status will contribute to a greater influx of post-war investment than before – for example, for Poland, the Czech Republic and the Baltic states admitted to the EU in 2004, the process of close integration with EU markets began as early as 2000, as a result of the provisions of association agreements and adjustment investments. The EU’s announced drive to regain “sovereignty” in the field of microchips is also a huge opportunity, as until now member countries have been dependent on their imports from Taiwan. Ukraine’s deposits of rare earth metals, however, open up the prospect of developing their intra-Community production after Ukrainian accession.

References

Davies, Lost Kingdoms, Krakow 2010, pp. 268-275.

The limits of linear consumption [online], https://reports.weforum.org/toward-the-circular-economy-accelerating-the-scale-up-across-global-supply-chains/the-limits-of-linear-consumption/

Hązła, Curator Economy in China – a response to the peculiarities of the market, or a harbinger of the coming changes in global e-commerce?“, “Gdansk East Asian Studies” 2022, no. 21, p. 100.

Observatory of Economic Complexity: Country Profile Russia [online], https://oec.world/en/profile/country/rus?yearSelector1=exportGrowthYear26&depthSelector1=HS2Depth

Natural gas, rare earth minerals: What’s at stake for Ukraine in the territory Russia is trying to conquer [online], https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/natural-resources-ukraine-war-1.6467039

Fight for Rare Earth Metals [online], https://www.obserwatorfinansowy.pl/bez-kategorii/rotator/walka-o-metale-ziem-rzadkich/

Ukraine energy profile: Energy Security [online], https://www.iea.org/reports/ukraine-energy-profile/energy-security

Why the Black Sea could emerge as the world’s next great energy battleground [online], https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/why-the-black-sea-could-emerge-as-the-worlds-next-great-energy-battleground/

Funding tracker: Who’s sending aid to Ukraine? [online], https://www.devex.com/news/funding-tracker-who-s-sending-aid-to-ukraine-102887

International sanctions are working: Russia feels economic pressure [online], https://ge.usembassy.gov/international-sanctions-are-working-russia-feels-economic-pressure/

Charles Michel: The EU is experiencing its Copernican Revolution [online], https://wyborcza.pl/7,179012,28221225,charles-michel-ue-przezywa-wlasnie-swoj-przewrot-kopernikanski.html

Kharas, The Unprecedented Expansion of the Global Middle Class: An Update, Washington 2017, pp. 15-16.

Rare earth metals. The bottleneck of digital civilization [online], https://www.rp.pl/plus-minus/art35711091-metale-ziem-rzadkich-waskie-gardlo-cywilizacji-cyfrowej

Mishchenko, Ukrainian Mineral Resources In The Market Transformations, “Ukrainian Journal Economist” 2012, no. 3, s. 55-58.

Lithium prices rose 496% through 2021 as many industries restarted after the COVID-19 pandemic, see How Metals Prices Performed in 2021 [online], https://elements.visualcapitalist.com/how-metals-prices-performed-in-2021/

Ukraine’s critical minerals and Europe’s energy transition: A motivation for Russian aggression? [online], https://www.mei.edu/publications/ukraines-critical-minerals-and-europes-energy-transition-motivation-russian-aggression

The Budapest Memorandum and U.S. Obligations [online], https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2014/12/04/the-budapest-memorandum-and-u-s-obligations/

Damage caused to Ukraine’s infrastructure during the war increased to $113.5 trillion, minimum recovery needs for destroyed assets is almost $200 trillion [online], https://kse.ua/about-the-school/news/damage-caused-to-ukraine-s-infrastructure-during-the-war-increased-to-113-5-bln-minimum-recovery-needs-for-destroyed-assets-is-almost-200-bln/

Allies freeze $330 bn of Russian assets since Ukraine invasion: task force [online], https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20220629-allies-freeze-330-bn-of-russian-assets-since-ukraine-invasion-task-force

Using Russian assets to rebuild Ukraine won’t be easy [online], https://www.ft.com/content/b77aa49d-1af6-4d2f-b509-ed302411f129

GDP (current US$) – Ukraine [online], https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=UA

Poland will help rebuild Ukraine after war ends: deputy PM [online], https://www.polskieradio.pl/395/9766/Artykul/2954748,Poland-will-help-rebuild-Ukraine-after-war-ends-deputy-PM

EU, Ukraine sign ‘strategic partnership’ on raw materials [online], https://www.euractiv.com/section/circular-economy/news/eu-ukraine-to-sign-strategic-partnership-on-raw-materials/

Ukraine’s possible EU accession and its consequences [online], https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/publication/ukraines-possible-eu-accession-and-its-consequences

Hązła, Should the European Union become a federation, “Society and Politics” 2021, no. 3/68, pp. 67-68.

Chips Act. EU will fight for its “sovereignty” over chips [online], https://wyborcza.pl/7,75399,28088437,chips-act-ue-zawalczy-o-swa-suwerennosc-w-dziedzinie-czipow.html#S.tylko_na_wyborcza.pl-K.C-B.3-L.1.maly