Despite Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, according to Serbia’s National Bank, the country’s record amount of foreign direct investment (FDI) in 2022 exceeded central bankers’ expectations. Aleksandar Vucic, the president of Serbia, praised the “great success in a year of fighting in Ukraine”.

By showcasing Vucic’s close ties to Moscow and his refusal to enact sanctions or a no-fly zone to punish Russia for its invasion, the war has strained relations between Brussels and Belgrade. According to certain analysts and data on new firms, the Russian and Ukrainian citizens who fled those countries and the exponential growth of Russian-owned company operations in Serbia may have contributed to the investment boom in Serbia.

Foreign Direct Investments and their positive effects

One way in which capital is moved internationally for investment purposes is through foreign direct investment (FDI). FDI is divided into two categories: inward FDI (or foreign direct investment into the economy, or foreign investment in resident enterprises) and outward FDI (or foreign direct investment abroad, or investment by residents in foreign affiliates), which is determined by the directional principle, or the direction of movement of investment capital on the line: country of origin – country of destination. In this analysis, we will focus on IFDI and ignore the many other categories and forms.

Numerous theoretical and empirical studies based on global experience have established the impact of FDI on the economy of the host country. It has been claimed that FDI has significant development potential and can have a variety of effects. In addition, it has been found that the capacity of the national economy depends significantly on the ability to take advantage of the favourable benefits of FDI that are now available. It is important to note that FDI can have negative effects on the environment and domestic enterprises.

Because of the link between new investment and economic growth, FDI represents a desirable additional inflow of foreign investment capital, especially for countries that do not have an abundance of investment capital. It should be remembered that domestic savings constitute the bulk of the investment capital stock.

Foreign Direct Investments in Serbia

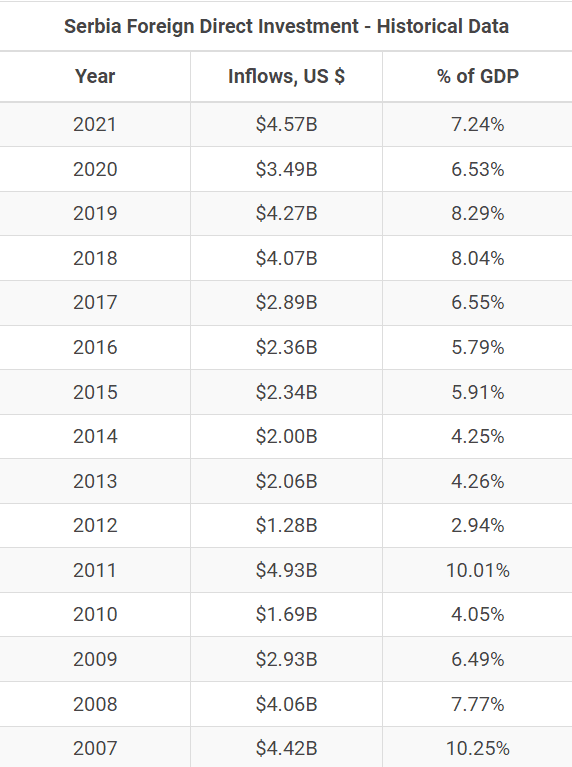

The efforts of the Serbian government to attract FDI and the results achieved in this regard have made the issue of FDI an almost constant topic in Serbian politics and the media. Numerical data will help us to understand the correlation between FDIs and GDP growth. Serbia’s economic growth rates from 2014 to 2021 are as follows: -1.6 per cent in 2014, 1.8 per cent in 2015, 3.3 per cent in 2016, 2.1 per cent in 2017, 4.3 per cent in 2018, 4.5 per cent in 2019, -0.9 in 2020 and 7.5 in 2021. The inflow of FDIs as shown in the table below is positively correlated.

It should be noted that investment is the main driver of economic expansion. Total investment in Serbia (public, public enterprises, local private sector and foreign) was 17.1% on average (2015-2017) and 18% (2018), compared to 20.4% in Western Europe and 21% in Central and Eastern Europe (as a share of GDP).

Only foreign investment is considered to have reached a reasonable level. A third of all investment comes from net FDI inflows, compared to only 7% of GDP from domestic private investment. This is the financial (capital) account of the balance of payments.

Source: Serbian National Bank

The composition of Serbian FDIs

It is possible to draw conclusions about the structure of a country’s economy by looking at the sectoral composition of its investment. The sectoral structure of an economy shows the intensity, concentration and corresponding technical level of production inputs (i.e. the factors required for production, such as labour, land, capital, resources and machinery). Because each good is produced with a different level of machinery and factor intensity, productivity improvements vary across industries. Thus, changes in the sectoral mix have a significant impact on the growth rate and income level of an economy.

For the Serbian economy, it is crucial that investment flows to agriculture and the real economy, which actually produces goods and services, as growth in these sectors could improve the country’s persistently poor trade balances. However, the sectoral organisation of investment in the Serbian economy reveals persistent problems with investment policy. More than 60% of all foreign investment is in services, where it is most concentrated. Up to 26 per cent of all FDI is in the financial services sector. Before 2014, the contribution of the financial sector was around 28 percent, which makes it much larger. The share of the financial sector in total FDI has declined slightly as a result of the influx of labour-intensive investments in recent years. However, the services sector is completely dominated by the financial sector, which accounts for around 35% of it. This is very similar to the global average of 34.3%. Only in the most industrialised countries is the share of financial services significantly higher, at over 39 per cent.

These factors set Serbia apart from the economies of the Global South, where financial services are a much smaller part of the economy. However, these figures do not reflect an increase in domestic production or production outsourced to another country. An expansion of the services sector in industrialised economies typically corresponds to extensive outsourcing of production. Value is created elsewhere, allowing for the potential growth of the domestic services industry.

Foreign banks, companies and other economic organisations are heavily focused on imports, the domestic market and favourable interest rates. Because of the limited economic contribution of investment in non-tradables, shopping centres and real estate, this has a negative impact on the balance of payments. Three very successful sectors – financial services, retail trade and telecommunications – have attracted a significant share of FDI. This suggests that, in this case, FDI has not made a significant contribution to the horizontal or vertical transfer of technology and know-how within the host country. It also suggests that FDI may boost imports more than exports, leading to a trade deficit rather than a surplus.

Due to the dominance of services and small, labour-intensive industries, there has never been significant investment in modern technology transfer, machinery or production management. However, it is important to remember that there has been a transfer of “know how” in the financial sector. This concerns the banking industry and the ongoing training of managers at lower levels. On the other hand, large financial institutions, insurance companies and multinationals often select foreign managers to run these private companies. The companies then move their ongoing research efforts abroad, which hinders rather than promotes the development of “human capital” in the host country. For Serbian lower-level managers, it could be argued that the methods of conducting financial business at home and abroad are combined. There are also trade spillovers, with a new ‘know how’ approach to dealing with consumers and education at all levels. However, the most significant spillovers in production haven’t yet taken place.

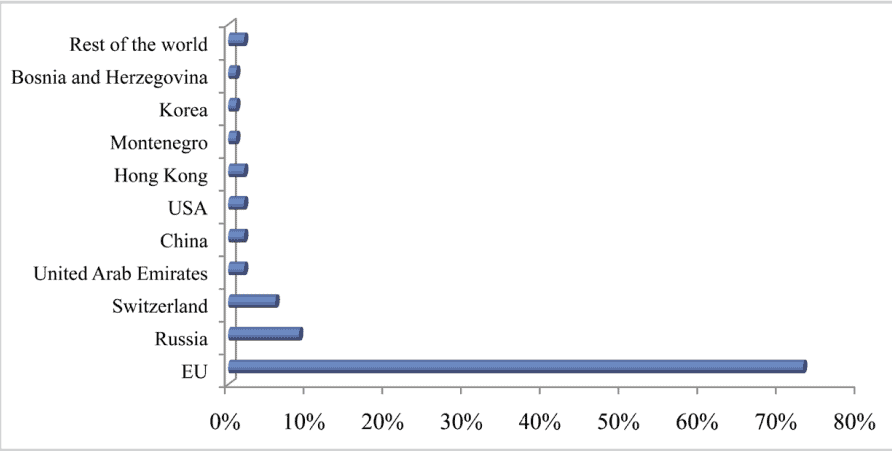

Most foreign capital comes from EU countries. Italy invests in the automobile, clothing and textile industries, as well as in banking and insurance (Fiat, Golden Lady, Fondiaria SAI, Intesa, etc.). The United States invests in glass containers, call centres, pharmaceuticals, metal can manufacturing, secondary non-ferrous metals and architectural services (Valeant Pharmaceutical, NCR, LC Comgroup, Ball Corporation). Austria invests in banking, telecommunications, real estate, car mechanics, production of plastic materials and insurance (VIP Mobile, Erste bank, Uniqa insurance, Raiffeisen bank, Porsche Holding). Greece invests mainly in banking (Pireus bank, Alpha bank, EFG Eurobank). Norway invests in telecommunications (Telenor). Germany is more diversified, with investments in pharmaceuticals, automobiles, commercial banks, cigarette shops, department stores, industrial gases, electrical equipment, metalworking, motors and generators (Stada Hemopharm, Metro AG, Siemens AG, IGB Holding, DM Drogerie). France invests in the banking sector, flooring retailers, advertising agencies and the food industry (Michelin, Tarkett, BSA, Credit Agricole, Societe General, Segur Development).

Source: Serbian National Bank (Cumulative FDI inflow 2010-2018)

Current trends in Serbian FDIs

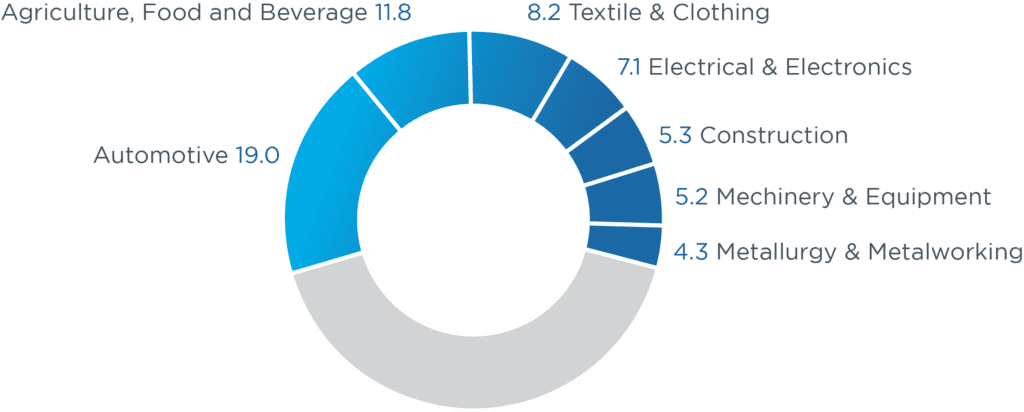

We can point to some dominant FDI trends in Serbia: Chinese companies have made three significant investments (in mining and metallurgy), as well as numerous investments in the automotive sector (Fiat, wiring, tyres) and Arab investments in agriculture.

In addition to Zijin and HBIS, Shandong Linglong Tire started the construction of a factory in Zrenjanin with an investment of 1 billion euros. The Michelin tyre factory in Pirot has been operating profitably for many years. Certainly, the FCA plant in Kragujevac has attracted related investments. Perhaps the largest part of the financial incentives has been used by five international wire companies for the automotive industry: Yura Corporation (Leskovac), Leoni (Prokuplje, Maloiite, Ni, Kraljevo), Delphi (Novi Sad), Lear Corporation (Novi Sad) and PKC Wiring Systems (Smederevo). The production of these companies is mainly characterised by low investment in equipment, the use of unskilled manual labour and a gender bias.

The Mei Ta car parts factory in Bari is more technologically significant. At the beginning of 2017, a brand new Continental-Contitech factory started operations near Subotica. We can also mention two significant UAE investments in Al Dahra’s agricultural sector: the purchase of PKB and Rudnap (orchards in Rivica and Irig). It is clear that Turkish companies have recently invested in Serbia’s previously highly developed textile and footwear industries. Etihad from the United Arab Emirates made a major investment in Air Serbia, and P&O Port Dubai from the United Arab Emirates took control of the port of Novi Sad.

From January 2018, Siemens took over Milanovi Engineering from Kragujevac on the production side. The owner of this company bought 70 hectares in the brand-new Sobovica industrial zone, where Siemens has built a new plant for the production of aluminium bodies for passenger coaches and will soon start producing trams. Siemens already has a plant in Subotica, where it manufactures wind turbine generators.

Although some of the FDI production is for the domestic market, most of it is export-oriented. The natural consequence is that exports will increase. Several years of experience show that Serbia’s largest exporters are also its largest importers (e.g. HBIS has to import iron ore and coke to produce and export steel; the same goes for Fiat in Kragujevac). Moreover, a significant part of the production of international companies is assembly-related. It would be more accurate to say that FDI increases the volume of trade.

The sectoral structure of FDI in Serbia indicates that it cannot help to catch up with the developed countries. There are only a few technologically advanced companies that can provide technology and knowledge spillovers as well as managerial talent (e.g. Siemens, Continental). The beginnings of clustering and the establishment of upstream and downstream linkages between local suppliers and the primary (foreign) firm are evident. However, as it is common for foreign investors to prefer to locate near similar firms, the alluring influence of already established foreign firms is evident.

There are, however, some encouraging statistics on the technological sophistication of future FDI. It could focus on ICT as well as mining and related sectors. Many foreign companies are exploring Serbia’s geology, and Rio Tinto has found a new mineral deposit near Loznica (called Jadarit). The site is estimated to contain 135,000 million tonnes and can supply more than 20% of the world’s lithium needs. The mine is scheduled to open in 2023.

ICT is another area of potential. Without any support from the government, exports of ICT services have recently surpassed corn exports. The establishment of a science park in Bora with Chinese support, the presence of Huawei and many other high-tech companies, and other factors will undoubtedly play a key role in the growth of the domestic ICT sector.

Source: RAS database 2022 (Percentage of projects funded by FDIs by sector)

Funding opportunities from the European Union

The EU supports reforms in the ‘enlargement countries’ with financial and technical assistance through the Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance (IPA). Throughout the accession process, IPA funding helps countries build their capacity, leading to forward-looking, beneficial changes in the region. IPA had a budget of €11.5 billion for the years 2007 to 2013, and its successor, IPA II, will build on these achievements with a budget of €11.7 billion for the years 2014 to 2020. The current beneficiaries are Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Kosovo, Montenegro, Serbia and Turkey. The EU’s pre-accession funds are a wise investment in the future of the enlargement countries and the EU. They help the recipients to carry out political and economic reforms so that they are ready for the responsibilities and rights that come with EU membership. These reforms should provide better opportunities and standards comparable to those we enjoy as EU citizens, which would also benefit the citizens of other countries. Pre-accession funds also help the EU to achieve its own objectives, including sustainable economic recovery, energy security, transport, the environment and combating climate change. IPA II focuses on reforms within the parameters of pre-defined sectors. These sectors cover issues such as democracy and governance, the rule of law, or growth and competitiveness, which are directly linked to the enlargement strategy. This sector-based strategy promotes structural changes that support a specific sector transformation and meet EU criteria. It allows for a shift towards more targeted assistance, ensuring effectiveness, sustainability and a focus on results.

IPA consists of five parts: Transition support and institution building come first, followed by international cooperation, regional development, human resources development and rural development. Both candidate countries – Turkey, Serbia (including Kosovo under UNSCR 1244), Montenegro, FYR Macedonia and Iceland – and potential candidate countries – Bosnia and Herzegovina and Albania – are eligible for IPA funding.

Initially, refugees from Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia, displaced persons from Kosovo, people with disabilities and dependent children were the main beneficiaries of humanitarian cooperation between Serbia and the EU. By 2014, the EU had provided a total of €2.6 billion in assistance to Serbia.

A wide range of initiatives have been implemented, including assistance in the fields of energy, transport, political reform, local governance, public administration reform, protection of minority rights, protection of fundamental human rights, development of civil society, regional cooperation, education and poverty reduction. Individual assistance has been provided to Serbia by the following countries, among others Germany, Italy, Sweden, Norway, Switzerland, the Netherlands and the UK.

![]()

Source: Serbian National Bank

Fostering FDI attractivity in Serbia

According to the OECD’s Investment Reform Index 2010, Bulgaria, together with Croatia, Macedonia and Serbia, has the most developed investment promotion agency in Southeast Europe.

Local governments and the Serbian government have invested a lot of time, money and effort (from the budget) in attracting FDI. The Serbian Government has set priorities in its Regulation on Conditions and Methods of Attracting Direct Investments. They are: the level of development of the investment location, minimum investments between €100,000 and €500,000, minimum number of new employees between 10 and 50, and maximum financial incentives for newly created jobs between €3,000 and €7,000. The government provides financial support for investments in food production, ICT export service centres and manufacturing. Local governments also often donate or lease sites, provide infrastructure, build access roads, etc. Other elements that attract FDI include the large amount of fertile agricultural land, a free trade agreement with the Russian Federation, and transportation costs, in addition to the incentives and guidelines that the Serbian government has established for foreign companies.

The Serbian government has established the following organisations to promote exports and FDI inflows: the Serbian Development Agency (RAS – SIEPA); the Development Fund of the Republic of Serbia; the Serbian Agency for the Development of Small and Medium Enterprises and Entrepreneurship; the Export Credit and Insurance Agency of the Republic of Serbia.

The Serbian Development Agency facilitates communication with potential Serbian subcontractors and assists international investors in selecting appropriate investment opportunities. The growth of investment relations is crucial for the Serbian economy. Its positive influence on the country’s employment policy is the key component of its social benefits. At the same time, the Agency’s initiatives help Serbian companies to become more competitive. RAS-SIEPA organises meetings of foreign companies looking for partners in the Serbian economy. In addition, the organisation provides financial support to Serbian companies to participate in international trade fairs abroad.

The Development Fund of the Republic of Serbia was established to promote economic and regional development, support the creation of small and medium-sized enterprises and increase the competitiveness of domestic commercial organisations.

A specialised financial organisation supporting Serbia’s export strategy is the Export Credit and Insurance Agency of the Republic of Serbia. The Agency’s main areas of interest include insurance of exportable goods, provision of guarantees, factoring, forfeiting, consultancy and technical assistance to exporters. Serbian businessmen are interested in this activity because it improves the positioning of Serbian products on global markets.

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) can get help from the Serbian Agency for the Development of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises and Entrepreneurship. It organises seminars for SMEs to inform them about current business-related legislation and the opportunities for EU financial support to improve their competitiveness.

A specialised financial organisation supporting Serbia’s export strategy is the Export Credit and Insurance Agency of the Republic of Serbia. The Agency’s main areas of interest include insurance of exportable goods, provision of guarantees, factoring, forfeiting, consultancy and technical assistance to exporters. Serbian businessmen are interested in this activity because it improves the positioning of Serbian products on global markets.

Conclusion

Investment is the main driver of economic growth in any country. Its main source is domestic savings, but it is also financed by foreign investment. Therefore, countries with enough money strive to attract more foreign investment, and countries that lack investment capital have another goal. The Serbian government has worked hard in all areas – legal, administrative, financial and political – to attract FDI. It has succeeded in achieving a number of goals, including an increase in employment, economic activity and trade volume. The initial consequences of the presence of FDI are more complex and dynamic. With domestic savings and investment at current low levels, is it reasonable to expect more?

References

http://www. kombeg.org.rs/Slike/CeEkonPolitikaPrestrIRazvoj/2015/avgust/Investicije%202015.pdf

Kordić, Ninela: Atraktivnost Srbije za privlačenje stranih investicija, Singidunum, Beograd, 2011

http://ekfak.kg.ac.rs/sites/default/files/Doktorske/DoktorskeDisertacije/Olgica%20 Nestorovic.pdf

https://rosalux.rs/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/108_foreign_direct_investments_in_serbia_ivan_radenkovic_rls_2016.pdf

https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/enlargement-policy/serbia_en

http://ea21journal.world/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/ea-V169-01.pdf

https://nbs.rs/sr_RS/indeks/

https://www.lloydsbanktrade.com/en/market-potential/serbia/investment

https://www.slobodnaevropa.org/a/srbija-strane-investicije-rekord/32199065.html

https://www.mining-technology.com/news/newsrio-tinto-signs-mou-with-serbia-to-develop-jadar-lithium-borate-project-5881303/

http://ras.gov.rs/en

https://fondzarazvoj.gov.rs/cir