According to a December 2021 PwC report,[1] the Polish housing sector has experienced remarkable growth in recent years. The prices of residential units (apartments) in major urban centres have increased by an average of 10 percent from 2017 to 2020. Additionally, this has been matched by a similar pace of salary rise. Between 2017 and 2020, the average monthly wage in the major cities increased by more than 20 percent. This may also be viewed as a natural increase implied by Poland’s demographics, where the number of households is expanding but the number of residences is still relatively limited, as demonstrated by a 2019 study:[2] “Poland currently lacks around 2.1 million apartments and by 2030, the deficit will have risen to 2.7 million due to the increasing number of households”.

However, following the year 2020, Poland’s housing market growth halted and the scenario completely changed, as market sentiment was negatively impacted by lingering pandemic fears, the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine, and rising inflation.

The average price of existing apartments in Poland’s seven largest cities (Warsaw, Gdask, Gdynia, Kraków, ód, Pozna, and Wrocaw) increased by 9.3 percent year-over-year in the first quarter of 2022, according to the country’s central bank, Narodowy Bank Polski (NBP).[3] Regardless of how much of that is inflation. When prices are adjusted for inflation, they actually decline by 0.4%. In fact, in the largest cities of Poland:

- The average house price in Warsaw increased by 5.1% between Q1 2021 and Q1 2022 (but declined by 4.2 percent when adjusted for inflation). This is a decline from the 8.9 percent price increases of the previous year.

- In the first quarter of 2022, Kraków experienced the biggest year-over-year increase in housing prices among Poland’s seven largest cities, at 19.5% (or 9% when adjusting for inflation).

- Other large Polish cities, such as Gdynia (15.3% house price growth), ód (14.4%), Wrocaw (14.2%), and Gdask (14.2%), also had significant price increases (9.9 percent).

- Among the seven largest cities, Pozna had the second-lowest annual price growth of 5.2% in Q1 2022, with prices reducing by 4% when adjusted for inflation.

To analyse further the market, we must take into consideration that demand is at the same time slowing; thus, the inflation of real estate prices is mainly cost-driven. According to JLL’s Q1 2022 Residential Market report,[4] the total number of new flats sold in the country’s six largest cities was close to 10,400 units in the first quarter of 2022, down by 31 percent from the previous quarter and by 46 percent from an extraordinarily high Q1 2021 result. This is in stark contrast to 2021, when – in the second stage of the pandemic – households begun to use funds saved the year before and sales of new apartments increased by more than 30 percent from the previous year to 69,000 units, following a 19 percent fall in 2020.

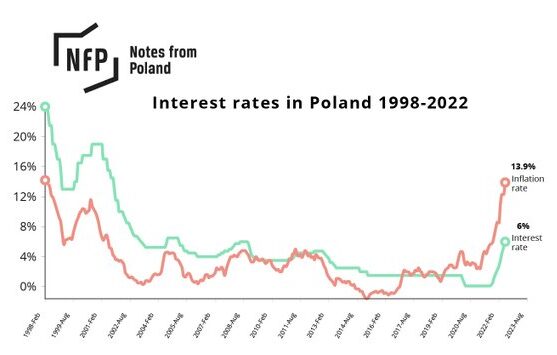

Furthermore, a series of prior interest rate hikes and their consequences on home loan interest rates have negatively impacted Demand. In addition, loan-backed purchases remained constrained due to the tightening of criteria for calculating creditworthiness. The likelihood of rising interest rates also hampered demand, resulting in increased mortgage costs. The market was dominated by cash buyers, whose judgments may now be increasingly influenced by price predictions for the near future.[5]

The housing market is highly susceptible to changes in interest rates. In general, the demand for homes decreases when interest rates and mortgage prices rise. In fact, the gradual rise in European house prices over the past decade has corresponded with record low borrowing rates in the EU.

From June 2014 until July 2022, the European Central Bank (ECB) maintained negative interest rates as low as -0.5 percent. With mortgage rates tied to central bank interest rates, the influx of inexpensive liquidity helped housing market expansion.

Since October 2021, the Polish central bank, Narodowy Bank Polski (NBP), has executed eleven consecutive interest rate hikes, making 2022 an extremely aggressive year.[6] In October 2022, interest rates have increased from a historic low of 0.1 percent in September 2021 to an astonishing 6.75 percent.[7]

With interest rates at multi-year highs, soaring construction material costs, and double-digit inflation, many Poles have been forced to sell their unfinished homes.

According to Business Insider Polska,[8] the number of active listings for unfinished homes sales by private sellers on Otodom,[9] a significant real estate sales and rental listing website, reached its highest level in three years during the first quarter of 2022.

Analysts at Pekao, one of Poland’s largest banks, indicate that the sales of new developments and restoration reported by publicly traded developers decreased by 22 percent year over year during the same time, the steepest decline in a decade.

After the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which resulted in sanctions against Russia and Belarus as well as the suspension of imports from Ukraine, the price of construction supplies – which had already been rising owing to pandemic-induced supply-chain difficulties – increased much more.

Can this be seen as a market bubble, and will there be a crash?

A housing market crash is a time in which real estate prices fall sharply. Typically, it is preceded by a housing bubble, a period of high real estate prices fueled by rising demand, inexpensive loans, and speculative interests. Nobel prize in Economics winner Joseph Stiglitz defined asset bubbles as follows:[10]

“If the reason that the price is high today is only because investors believe that the selling price is high tomorrow – when ‘fundamental’ factors do not seem to justify such a price – then a bubble exists.”

Long has it been believed that real estate prices are immune to market crashes and will only rise over time. However, housing markets are sensitive to external factors such as supply, demand, and interest rates, and can experience cycles of boom and bust.

A year and a half after the pandemic, we have witnessed the biggest hikes in housing prices in Europe. This was mostly attributable to the extremely low interest rates prevalent in 2020 and 2021, as central banks were compelled to reduce borrowing costs to encourage economic development during global lockdowns. Increased housing demand as a result of worldwide social trends such as telecommuting also supported prices.

Following a transitory decline in housing activity in the first half of 2020, property building and transactions returned in the second half of that year, as economies reopened and borrowing rates reached all-time lows. Concurrently, interest for the Polish home market was high as housing construction activity reached a record high by the end of 2020. In the fourth quarter of 2022, the number of homes completed in Poland reached a new peak.[11]

As demonstrated by Eurostat’s deflated HPI growth rate, the Polish housing market displayed signs of overconfidence in 2020. The deflated HPI removes inflation from the HPI and is regarded a crucial element for the analysis of house price cycles. The agency elaborated:[12]

“In particular, a too high growth rate is considered an early warning indicator of tensions in the real estate market signalling the risk of price bubbles. The alarm threshold adopted in the context of the MIP is 6 % of annual growth rate in the deflated HPI.”

Although it is safe to say that the market is undergoing a strong turbulence, the current Polish scenario isn’t classifiable as a bubble tout court. For the sake of comparison, we can take into account 2008 Polish real estate bubble when housing prices also rose drastically: Between June 2006 and June 2007, the average price per square metre of residential area in Warsaw increased by 50 percent, from 6,683 PLN (1,636 EUR) to 9,540 PLN (2,514 EUR).

While it is important to stress again that we are now experiencing mostly cost-driven inflation, at that time there were market fundamental conditions that differed from today:

- The Polish economy showed signs of overheating as its GDP growth rate declined.

- Credit limitations were extended enormously, banks – for instance – decided to lengthen loan terms from 30 to 50 years, while family debt grew substantially.

- The supply of housing kept growing despite the fact that sales had started to drop, initiating a stagnation of prices.

Real Estate markets are therefore entering a stage that had never be seen; commenting Warsaw’s residential housing market, the CBRE Group – a US commercial real estate services and investment company – stated that:[13]

“The market is entering a phase of reduced demand with limited supply. In the coming months, we will observe an increase in the available offer of flats for sale, although some projects may be postponed…Prices are likely to continue to rise, primarily due to increasing construction costs.”

Morgan Stanley, talking about US real estate market in an article titled “Prices rising, not bubbling”, noted that:[14]

“Rising mortgage rates have historically put the brakes on home-price appreciation, but this housing market is like no other. Record-low supplies, years of conservative lending and other factors suggest that home prices should continue appreciating, though at a slower pace.”

What can we expect from the near future for the Polish housing market

Similar to the previous quarter, it was difficult to find any good market signs during the last three months. The attack on the Nord Stream pipeline has increased concerns about gas supply and the security of essential infrastructure, and the German government anticipates a recession in the coming year. In Poland, inflation surged a bit more quickly than many experts anticipated, and its peak is likely still to come. Interbank interest rates and mortgage loan interest rates have climbed, and additional rises are anticipated in this instance. Compared to the previous quarter, consumer mood, particularly about real estate purchases, decreased. Given the possibility of heating and energy issues, it is also difficult to anticipate that winter will bring a noticeable change in mood. In addition, the election campaign before legislative elections will have a growing impact on the government’s strategy toward the residential development industry.

2023 will be a challenging year for the real estate development industry. With declining sales, developers should cut the number of units offered to the market accordingly. Due to a fortuitous occurrence, the timing of the Developer Guarantee Fund Act’s coming into force in the middle of the year encouraged businesses to grow their supply at a time when they must minimize it at all costs. Increasing project finance costs and sluggish sales will certainly result in a significant slowdown of new construction projects next year.

As it did in 2009 in reaction to the financial crisis, the government should implement a temporary program to assist prospective buyers in this circumstance. Recall that in 2009, the government modified the provisions of the Family’s Own Home program in order to support the demand slumping due to the global economic crisis. During 2009-2013, on the primary market alone, over 51,000 loans were authorized in which the state returned fifty percent of the interest on mortgage loans for the next eight years.

Sources

- https://www.pwc.pl/pl/pdf-nf/2022/PwC_Report_What_is_behind_the_boom.pdf ↑

- https://tvpworld.com/40737411/poland-lacks-over-2-mln-flats-report ↑

- https://www.nbp.pl/homen.aspx?f=/en/publikacje/inne/real_estate_market_q.html ↑

- https://www.jll.pl/content/dam/jll-com/documents/pdf/research/emea/poland/en/jll-pl-en-residential-market-in-poland-q12022.pdf ↑

- https://www.jll.pl/content/dam/jll-com/documents/pdf/research/emea/poland/en/housing-market-in-poland-Q3-2022.pdf ↑

- https://businessinsider.com.pl/twoje-pieniadze/rpp-podjela-decyzje-stopy-procentowe-znowu-w-gore/9ek0qhx ↑

- https://www.nbp.pl/homen.aspx?f=/en/dzienne/stopy.htm ↑

- https://businessinsider.com.pl/wiadomosci/rynek-nieruchomosci-tak-koncza-sie-marzenia-polakow-o-wlasnych-domach/lv483xj ↑

- https://www.otodom.pl/ ↑

- https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/089533005775196769 ↑

- https://www.nbp.pl/en/publikacje/inne/annual_report_2020.pdf ↑

- https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Housing_price_statistics_-_house_price_index#Annual_and_quarterly_growth_rates ↑

- https://www.cbre.com/insights/figures/warsaw-residential-q1-2022 ↑

- https://www.morganstanley.com/ideas/housing-market-and-rising-rates ↑