This article won the 2021 Blue Europe Young Academics contest, thanks to its pedagogic qualities.

Addendum 21/03/2022: The paper was written and accepted before the war in Ukraine started. It is to be understood in this vein.

INTRODUCTION

Names often contain the true meaning of things; they genuinely recall a or simplify an abstract concept or idea: Ukraine literally means ‘on the border’ (u krajna). A border area, always contested and conquered by powerful neighbours.

Because Ukraine is a borderland in the heart of Europe, it is a place of passage and human movements, first between Asia and Europe when the latter was weak, and subsequently between European states and European Russia when these two had grown strong in comparison to Asia. This country, described as a nation of warriors by Herodotus, fought when it attempted to be powerful and when it tried to conserve itself, including its weaknesses.

What we do not understand about present tensions and conflicts between Russia and Ukraine, below mainstream emotional information, is that they are the same tensions and conflicts that always torn the land at the border. Unfortunately, solutions that are being proposed are such as the old ones and suggest this region to be once again limes of the ‘known world’.

Ukraine is vast frontier right in the centre of our continent. It is, after Russia, the largest country in Europe with its 603,700 square kilometres and the fifth largest in terms of population (48 million of inhabitants). It is an open land, mostly flat (if we exclude the Green Carpathes Mountains to the south) and therefore without great natural defences apart from the Dnieper River, which, other than being the propulsion of Ukrainian civilization, emphasizes and metaphorizes the concept of division. Because of its unique physical characteristics, the region occupied by modern-day Ukraine has seen the arrival and departure of Cimmerians, Scythians, Sarmatians, Slavs, Bulgarians, Khazars, Magyars, Pechenegs, Cumans, and others.

Perhaps current events in this region offer us the opportunity to think at new ways of looking at our continent, ways that might even imply finally recognizing Europe as a peninsula of a much broader area.

The Pereiaslav Agreement was an official gathering held in January 1654 in the central Ukrainian town of Pereiaslav for a ceremonial promise of allegiance by Cossacks to the Tsar of Russia.

UNDERSTANDING ANCIENT HISTORY OF THE REGION

Although traces of human presence can be found in the region of today’s Ukraine dating back as far as the palaeolithic period – with a special note for the settlement of Trypillia, which stood out for its great agricultural development – the iron age, i.e. the establishment of a true civilisation, is characterised by the presence of The Cimmerians.

They are the first known pastoral Iranian tribes in modern Ukraine, who inhabited the steppe areas around the XV century BC coming from Central Asia through the Caucasus. The Cimmerians occupied a large area between the Dniester and the Don, as well as the Crimean Peninsula, where they built fortified settlements. It was them who built it around 1250 BC the first known port city on the territory of Ukraine; their main occupation was military campaigning.

In the VII century BC the Cimmerians were driven out of the steppe by the Scythians who also were a pastoral and warlike nomad population. Thanks to close trade and cultural ties with the Greek colonists of the Northern Black Sea, their culture, way of life, mythology and customs were well described their contemporary ancient Greek historian Herodotus. The Scythians, under the influence of the Greeks, gradually moved to a settled way of life, forming the first unitary state.

In the second and third centuries, the Scythians[1] were gradually pushed out of by another nomadic pastoral Iranian tribes, the Sarmatians. These peoples are well known for their high military skills and strong physiques, for example heavy Sarmatian cavalry was highly demanded by the Roman army in various parts of the empire.

During the VIII century BC, Greece experiences a population explosion. The lack of fertile land, led to a massive Greek colonization of the Mediterranean (according to the ancient Roman historian Plutarch, the Greeks settled on the shores of the Mediterranean “like those frogs on the shores of a pond”).

Greeks brought along their culture and their advances in science, medicine, architecture, art, craftmanship, urban planning and – of course – social organization which had a great impact on the civil development of the area.

After the division of the Roman Empire into Western and Eastern, the Northern Black Sea came under the strong Byzantine influence.

In the middle of the III century Scandinavian tribes of Goths moved from the Vistula River to the land of the legendary fertile Oyum (another name for Scythia, where the Goths, under a legendary King Filimer settled after leaving Gothiscandza). Their military skill and leadership ramification allowed them to conquer vast territories in Eastern Europe, defeating the Iranian Sarmatian tribes. This led to the founding of their own kingdom.

This state was then destroyed in 375 AD, when it came under the attack by the union of nomadic Hun tribes led by Attila.

From the ninth century, Scandinavian sailors established a new trade route to the south[2], called the way from the Vikings to the Greeks. It started from Lake Ilmen, passed through small rivers and then through the Dnieper to the Black Sea.

Kyiv obviously played an important role due to its location at the confluence of the three largest arteries of Russia (Dnieper, Pripyat and Desna). That is why a certain union of tribes is beginning to form near Kyiv, leading to what we know as Kievan Rus[3].

Traditionally, the first ruler of Kievan Rus is considered to be Prince Oleg who took over Kiev in 882. His son Vladimir the Great expanded the territory of the state, rebuilt Kiev, and finally christened Russia.

This kingdom was more of a pawn than a manoeuvring force though: if on the one hand it succeeded in arising because it brought together various Slavic tribes around the project of exploiting the intermediate position between rich Eastern Roman Empire and the first poor Norman kingdoms; on the other hand, the acceptance of the Orthodox Christian religion, made them a Byzantine pawn (Constantinople used Ukraine for its own purposes, hurling it for example at the Bulgarian Empire).

After glorying in its own national greatness, the Russian state of Kiev split into various principalities only to be overwhelmed, now disunited, by yet another wave, this time represented by the Mongols or Tatars.

While the Mongols made the various Russian principalities their vassals, one stood out, still considered the true cradle of Ukraine, the principality of Prejaslav (in the area near Kiev), which was therefore Ukraine, ‘on the border’. To seek shelter, Russian peoples began to move northwards, to areas that were quieter and less vulnerable to an invasion.[4]

By now they had realised that life there was impossible, and with them, thanks to some visionary leaders, the name Russia, born between the Dnieper and the Black Sea, moved northwards, to Muscovy, which was to become modern and contemporary Russia.

Russians attested to their imperial and international power as stabilisers of the central and northern area of Eurasia, rendering an epochal service to Europe as well as to China and India. Ukrainians were at this point squeezed between themselves and the other Slavic states that were springing up in the West.In the 13th century, the Tatar-Mongol invasions from the eastern steppes marked the final epilogue of the Kievan Rus’ state. From its erosion, several principalities were established, all stemming from what had been a large Slavic state entity and distilling their own distinct history and culture in the centuries to come.

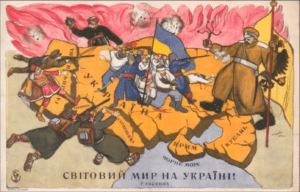

In this 1919 cartoon, Ukrainians are encircled by a Bolshevik (to the north, wearing a helmet and red star), a Russian White Army soldier (to the east, carrying a Russian eagle flag and a short whip), a Polish soldier, a Hungarian (wearing a pink outfit), and two Romanian soldiers.

UNDERSTANDING MODERN HISTORY OF THE REGION

From the 16th century the territory of Ukraine was controlled by the Commonwealth of Poland-Lithuania[5], one of the largest states of the continent in the early modern period. Poland Lithuania waged permanent wars with its neighbours: Muscovy in the east, Sweden in the north, the Ottoman Empire and the Crimean Khanate in the south.

The Ukrainian peasantry increasingly felt the oppression of serfdom by Szlachtamagnates; this widespread intolerance combined with the Polish pressure on the west brought to the great Cossack uprising of 1648 against the Commonwealth, led by Bohdan Khmelnitsky.

Cossacks were remains of that free-nomad world of the steppe and, as they couldn’t secure a stable alliance with the Ottoman Empire – mostly over ethnical and religious qualms –, turned to Muscovy to fight the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. This decision led to a division of Ukrainian territory, marked by the Dnieper, between the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Moscow State. These events brought the name ‘Rus’ up north towards Moscow. As a matter of fact, after defeating Sweden and consolidating his powers, Peter I founded the Russian Empire, attempting to restore a Pan-Slavic nation under the ancient myth of Kievan Rus’.

Like any other European nation, the 18th century for Ukraine was characterised by strong social uprisings and unrest, the victory in the war over Napoleon, for instance, inspired members of progressive masonic lodges to work to transform Russia[6] into a constitutionally ordered democracy. After St. Petersburg, the broadest field of activity of the Decembrist movement was Ukraine. In 1821 the Southern Society and the Society of United Slavs were formed, starting three decades of uprisings and instability.[7]

Moreover, during the Turkish-Russian war, Great Britain, France, and the Kingdom of Sardinia sided with the Ottoman Empire, starting the Crimean War (1853-1856). Meanwhile, peasants of the Kyiv region formed the ‘Cossacks of Kyiv’, a popular movement of peasants who organized self-governing communities and refused to perform their duties.[8]

After the war and Russia’s Empire humiliating defeat, multiple social reforms started in what seemed to be the beginning of a new era for Ukraine as an independent country – serfdom for example was abolished.

In 1900-1903, because of the intensive industrialization to regain the lost status of Russia, the first economic crisis of overproduction took place. The deterioration of working conditions combined with the loss in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905) created a general depressive mood all over the Empire. On January 9, 1905, the First Russian Revolution began; in Kyiv, insurgent workers formed their own republic. To confront the Ukrainian revolution, an ultra-nationalist and reactionary movement named ‘Black Hundreds’ was formed. This monarchist movement who arose in defence of the House of Romanov went as far as organizing pogroms against the Jewish community and revolutionaries.[9]

When the State Duma was formed, Ukrainian deputies obtained seats and formed their own faction: the Ukrainian Parliamentary Community, even though they were progressively deprived of their powers.

During WWI, the Main Ukrainian Council was established in Lviv to support the Germans in the war against Russia. Volunteers’ divisions were in fact formed to fight alongside the Central Powers. In 1914, because of the Battle of Galicia, Tsar’s troops occupied the region and formed a governor-general’s office beginning the persecution of Ukrainophiles, a sentiment against the ‘treason’ of Ukraine that will live long the decades.

The enthusiasm for the beginning of the Ukrainian revolution arose from the well-known February Revolution in the Russian Empire: an alternative centre of power was formed in Ukraine – the Ukrainian Central Rada (UCR) – which led the national democratic revolution in Ukraine.

After the Bolshevist revolutions took place, the Ukrainian People’s Republic was established thanks to the cooperation of Ukrainian revolutionaries against the White Army. The synergy based on common struggle, however, lasted just a year.

In 1919, Ukraine declared autonomy and subsequently independence, which irritated Lenin, who chose to advance Bolshevik soldiers into the territory of the Ukrainian People’s Republic, resulting in a Ukrainian-Soviet war with horrific civilian losses. During this struggle, the Ukrainian People’s Republic was defeated, and the Bolsheviks conquered Ukraine, becoming the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, which was annexed to the newly founded Soviet Union.

Between 1917 and 1921, Ukraine experienced various forms of national statehood. Ukrainian ethnic territories were divided between the Ukrainian SSR, the Polish Republic, the Kingdom of Romania, and the Czechoslovak Republic. Thus, the Ukrainian national-democratic revolutionary spirit was defeated with a simple divide et impera strategy. The end of the revolution was the result of the incoherence of the political elite that formed its vanguard. Nevertheless, it laid the foundation for the nation-building process.

Then, between 1921 and 1923 the first Holodomor of the Ukrainian people occurred. Holodomor is a term derived from the Ukrainian words for hunger (holod) and extermination (mor), it refers to one of the greatest humanitarian catastrophes in the history of Eastern Europe. A brutality planned in a scientific and inhuman way, as scientific and inhuman as the ideology that formed its basis, soviet communism. In those years hunger affected not only the territory of Ukraine, but also the more prosperous parts of Russia, yet Lenin decided to send aid only to Russia, completely neglecting the suffering of the Ukrainian people both as a punitive tool against independent movements that were opposing the only accepted ideology and as a way to accelerate the process of collectivization through poverty. According to the Nansen Committee’s estimates, about 8 million peasants in the south of Ukraine went hungry during the winter of 1922. The exact number of victims is not known, but according to various estimates, at least half a million Ukrainians died of starvation between 1921 and 1923.

In the second half of the 1920s, Stalin, in the grip of the most lucid of utopian delusions, decided to completely redesign the vast territory that then constituted the USSR, both socially and economically, with the aim of establishing an economy and a society entirely governed by the Communist Party. The wealth created by agriculture was to be completely reinvested in the industrial sector, which represented the new flagship of the planned economy. From 1927 Stalin, in the purest Marxist fashion, ordered the collectivisation of all land into agricultural cooperatives (Kolchoz) or state-owned enterprises (Sovchoz), which were obliged to sell their products at the price set by the state, which owned and controlled everything.

Moreover, 80% of Ukraine’s inhabitants were peasants and small proprietors with a holy attachment to the land, which the internationalist communists could neither comprehend nor tolerate. The kulaks were a hindrance, therefore Stalin planned to exterminate them.

Then, after launching a despicable outrageous campaign in the vein of the Nazi campaign against the Jews – blaming these smallholders for every misdeed and horror, labeling them as brigands, looters, and people’s exploiters – he launched the famous and ill-fated five-year plan, which instead of creating paradise on earth, caused hell.

As a result, from 1929 onwards, a significant number of Bolshevik commissars were dispatched to seize land from Ukrainian small and medium landowners, and kulaks who attempted to fight were massacred.

Without the slightest modesty, Stalin dubbed this heinous practice ‘dekulakization’, which meant ‘disinfestation of dangerous germs, absolute bodily destruction’. The kulaks were punished with their own weapon, namely, the pulverization of their modest private property-based wealth.

The oppression was severe. The Ukrainian peasantry was subjected to mass deportations, killings, and imprisonment in gulags. Entire families were slaughtered, including the elderly, women, and children.

The few survivors died of famine or lead poisoning, especially after Stalin decided in 1932 to boost the region’s yield by putting to death all individuals who were condemned for stealing due to their objective incapacity to fulfil the purpose. Repression rose substantially at the end of 1932. Food was seized, and anyone caught hiding a peel or a crust was sentenced to death.

The accounts of these terrible events are endless. They tell of Ukrainian girls whose tiny skeletal bodies were constantly dragged through the streets; they tell of a landscape awash by dying carcasses. These are stories of suffering, tragedy and death. Stories of parents who saw their children die in their arms from hardship. Stories of cannibalism that we should not go into detail about.

The death toll of this immense carnage is estimated at 7-10 million according to a joint statement at the United Nations signed by 25 countries[10], a holocaust directed at the extermination of white Europeans by the communists, so acclaimed by the western left. It is impossible to have a precise estimate of the number of victims, not least because the USSR did everything in its power to conceal these atrocities and in doing so found the support of the Western cosmopolitan and progressive cultural elites.

Unfortunately, still today, in many parts of the world the Holodomor is an unknown page of history, even if with the passing of 16 countries have signed to recognise the genocide.

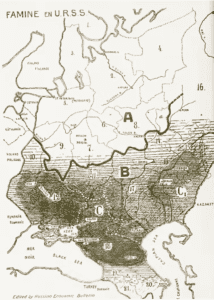

The worst-affected districts of the Soviet famine of 1932–1933 are depicted in black on this map. Ukraine is denoted by the number 12.

Since 1934 it was forbidden to reproduce artistic works with the characteristics of the Ukrainian people and it was made forbidden to study the real history of Rus-Ukraine. The regime began to persecute artists, historians and writers who, consciously or not, did not represent the ‘reality’. The culmination of the Soviet repressive machine came on 3 November 1937, the day on which in the name of the 20th anniversary of the Great October Revolution, several Ukrainian scientists, writers, activists, artists and poets were shot in the Solovky special camp.

On 17 September 1939 the USSR, on the basis of the Ribbentrop-Molotov pact, together with The Third Reich, invaded the eastern part of Poland. During the spring of 1940, more than 20,000 Polish army officers were executed in the forest near Katyn village by the Red Army.

In 1941, during the retreat of the Red Army and the German advance, the regime executed more than 3,500 people in Lviv, more than 3,000 in Lutsk and several thousand were eliminated in prisons. In total, the Bolsheviks executed more than 200,000 Ukrainians directly in jail. All these shootings were carried out in accordance with Lavrentiy Beria’s orders of 25 June 1941, under the cover of the ‘Prisoner Evacuation Plan’.

In October of the same year, in the village Nepokryte (today Shestakove), near Kharkiv, the communists burnt alive about 300 people locked up in a barn; they were part of the Ukrainian intelligentsia and among them was famous poet Volodymyr Svidzinskyi.

During WWII Ukraine became under the Third Reich control. Soon the war-like spirit of the Ukrainians arose, and the Resistance Movement formed. It had two currents: nationalist in the west and pro-Soviet in the east.

German intelligence used the radical wing of the OUN (Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists) for sabotages and propaganda against the Soviets, creating battalions ‘Nakhtigal’ and ‘Roland’. Today we can notice, mutatis mutandi, a resemblance with the actions of Ukrainian neo-nazi movements such as the Azov Battalion and the spread of anti-Russian sentiment. The nationalists hoped indeed to use the Germans to restore Ukrainian statehood.

After the ‘Iron Curtain’ had been dropped over Europe with the Potsdam Agreement, Ukraine came back solidly under the control of the Soviet Regime, although this time communists considered neighbouring Ukraine to be full of traitors.

In 1946-1947 the regime carried out a third Holodomor on Ukrainian territory, which resulted in the death of approximately 1.5 million Ukrainian peasants.

Following Stalin’s death (1953) his policy continued for some years. In 1956, however, during the 20th Assembly of the Communist Party of the USSR, the so-called ‘Cult of Personality’ of Stalin was partially condemned. Thus began a period which, historically, is called the ‘Khrushchev Thaw’.

This period, however, did not last long: neo-Stalinism was born in Moscow with Leonid Brezhnev in power, repeating the methods of the Stalinist era: mass arrests, closed trials, shootings, genocides, forced Russification and the revival of the ‘personality cult’, this time directed at Brezhnev.

In 1965, another wave of arrests of Ukrainian scientists, writers and students. More than 75 young people were arrested for distributing Ukrainian literary works guilty of ‘anti-Soviet propaganda’ and ‘bourgeois nationalism’.

With the above-mentioned arrests, the regime hoped to intimidate the rest of the Ukrainian intelligentsia, but this had the opposite effect, so much that in 1972 the second wave of repression against the Ukrainian intelligentsia began: about 100 activists were arrested, thousands of perquisitions were carried out, many people were terrorised during interrogations, fired from their jobs and expelled from universities. Most of the activists of the 1960s were sentenced to 7 years imprisonment in camps and deportation. A final purge against anti-Soviet activists came between 1979 and 1982.

The Soviet regime not only carried out brutal repression, but also had no respect for human life, and its industrial plants produced without any regards for safety and functionality. This modus operandi caused several tragedies, resulting in the deaths of thousands of people, one of which was the infamous Chornobyl nuclear tragedy in 1986.

On 16 July 1990, during the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the new Parliament adopted the Declaration of Sovereignty of Ukraine which established the principles of Ukraine’s self-determination and the priority of Ukrainian law on Ukrainian territory over Soviet law. A year later the Ukrainian parliament adopted the Act of Independence of Ukraine, through which the parliament declared Ukraine an independent and democratic state: Leonid Kravčuk was elected as the President of the Parliament to serve as the country’s first President.

On August 24, 1991, the Parliament of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic declared the independence of State, in connection with which the Ukrainian SSR ceased to exist; 90.3% of the population supported the independence.

This act summarizes the process of Ukrainian statehood creation that begun with the first unification of Slavic populations and later on continued throughout the many movements for regional independence, the same autonomist drives that ended up to be exploited – and whom will be inevitably taken advantage of again and again – by foreign powers cynically fighting for interests always bigger that Ukraine.

Sources

- https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2017/sep/17/scythians-warriors-of-ancient-siberia-british-museum-review ↑

- http://www.encyclopediaofukraine.com/display.asp?linkpath=pages%5CV%5CA%5CVarangianroute.htm#:~:text=A%20medieval%20trade%20route%20extending,the%20Varangians%20to%20the%20Greeks. ↑

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/Rus ↑

- https://geohistory.today/mongol-empire-effects-russia/ ↑

- https://www.britannica.com/event/Union-of-Lublin ↑

- Alexander Pypin, Freemasonry in Russia: XVIII and First Quarter of the XIX Century ↑

- Oksana Kryzhanivska, Secret Organizations and Masonic Movement in Ukraine ↑

- http://www.encyclopediaofukraine.com/display.asp?linkpath=pages%5CK%5CY%5CKyivCossacks.htm ↑

- http://www.encyclopediaofukraine.com/display.asp?linkpath=pages%5CR%5CE%5CRevolutionof1905.htm ↑

- https://web.archive.org/web/20170313040724/http://repository.un.org/bitstream/handle/11176/246001/A_C.3_58_9-EN.pdf ↑