Originally published on the Macedonian Academic Blog “Respublica” on December 29, 2023.

Disclaimer: Due to personal political standpoints, the author avoids to use the prefix “North” in reference to the country officially known as The Republic of North Macedonia after the 2018 Prespa Agreement (Final Agreement for the settlement of the differences as described in the United Nations Security Council Resolutions 817 (1993) and 845 (1993), the termination of the Interim Accord of 1995, and the establishment of a Strategic Partnership between the Parties).

At the beginning of December 2023, the European Parliament adopted [1] the plan for implementation of the legislation for critical and rare raw materials. This legislation, for those who are not concerned directly from mining and metallurgy, does not hold a big meaning, but seen from other perspectives, people’s everyday life highly depends on materials that are mentioned in this legislation.

The Critical Raw Material Act (CRMA) is an essential part of the big Green Agenda of the EU for decarbonisation of the industry and maximum decrease of usage of fossil fuels. The whole process of decarbonisation requires increased usage of batteries, solar panels, and permanent magnets, while their production further creates a bigger need for rare materials, their extraction from the soil and processing.

The ambitious plan of the European economy for full transition towards so called green energy, dictates the rhythm and demand for natural materials, but also places an emphasis on the dependence of the EU on China. On the list of countries that have natural ore deposits of critical raw materials, China is the leading one and supplies the world market with participation of 60%, while dependency of the EU on import of raw materials from China reaches almost 90%.

What raw materials is the EU dependent on and where are they used?

Apart from the process of decarbonisation, metals from raw materials are used in all industries for the production of mobile phones, communication technologies, automotive industry (electric vehicles), strategic technologies in military and space industries.

The list of the critical and rare materials contains 34 metals [2] which are categorised in groups of strategic and critical materials. The list of strategic materials contains the following: aluminum, copper, cobalt, lithium, gallium, manganese, germanium, natural graphite, antimony, bismuth, titanium, boron, tungsten. On the other hand, rare materials contain metals that are rarely found in the soil like hafnium, niobium, neobidium, strontium, beryllium, vanadium, cox (product of coal used as fuel).

From this list of materials, China holds the world market in processing of natural graphite with 100% [3] participation, 90% of manganese, 70% of cobalt, 60% of lithium and 40% of copper. On the opposite side, the EU is the biggest importer of cox that is used as a fuel in metal processing and 76% of the imported zinc comes from the USA.

The dependence of the world, especially the EU and the US, on China’s mining and processing of metals is based on the fact that China not only processes 60% [4] of rare minerals used as components in high technology, including smart phones and computers, but also contributes 13% to the world market for lithium, while processing 35% of the world’s demand for nickel, 58% for lithium and 70% for cobalt.

On the other hand, the dependency of the EU and the US on critical raw materials is visible from the point of view of figures, and if we add the fact that the rapidly growing Chinese economy and its spread around the world through the Belt and Road Initiative also includes investments in black and coloured metallurgy and investments in the mining sector. We have examples of these activities in our neighbourhood, in Serbia. In our country, China is present in the steel company in Skopje, while in Serbia it is present in the steel plant in Smederevo (HBIS) and in the mining centre and mine Bor RTB in eastern Serbia, where the Chinese conglomerate Zijin has the dominant percentage of shares in RTB Bor, the largest copper mine in Europe.

Trying to limit dependency on China.

With the legislation on critical raw materials, the EU aims to limit its dependence on materials that are in China’s possession. Although this is not explicitly stated in the legislation, it is written as ‘dependency on third parties’ and the gaze is discreetly turned towards China.

The targets that the EU has set to reduce the dependency until 2030 [5] are as follows: the extraction to be at least 10% on annual level from mines in the EU, at least 40% on annual level the processing to be done in EU factories, at least 25% of the needs for metals on annual level to be covered by recycling. The import dependence, the EU plans to reduce it to 65% on annual level for the strategic materials, without mentioning the party or who are the third countries from which the EU plans to become independent.

One of the measures that the EU is planning to implement in order to distance itself from China is the creation of a so-called Critical Raw Material Club for like-minded countries that will strengthen the raw material supply chain. This club is nothing new, but it is a strong political signal that the EU wants countries that will obediently follow and supply the Union with raw materials, while at the same time pursuing the same foreign policy as the EU towards countries that are not in the same club of thinking. This strategy will be implemented, as before, with political and economic pressure.

As promising as the plan to move away from China sounds, it is easy to identify and predict problems that are already visible. One of the problems is the poorly developed system for recycling metals already used in various products.

This does not refer to the recycling of metals used in the production of mobile phones or computers, but to the recycling of lithium batteries [6] and parts of the solar panels. Although there are big announcements about the construction of factories for the production of lithium batteries (the first one should be in Cuprija, Serbia), there is not enough discussion about the development of systems for the recycling of large lithium batteries, especially those from cars. The other long-term problem is the maintenance and protection of the environment around the tailings of abandoned mines and the conversion of the land around these mines into arable land.

Such strategies are seldom used even for copper, zinc and lead mines, which are widespread throughout the world, as they are in our region. Lithium, the most sought-after metal for batteries, is not easily found in high percentages in its ore, as is the case with copper or zinc. As a result, the extraction and processing of lithium alone requires expensive technologies and even more expensive recycling systems.

The third problem, which is already present and will become even more visible, is the pollution of the environment around the mines, the use of labour from third countries (mainly South America and Africa), the lack of environmental protection by the mining companies and the lack of exchange of know-how between the countries that have the mineral resources and the foreign companies that extract them. Rich countries are rarely interested in this problem, because for centuries it has been their practice to extract mineral resources and leave the local population in poverty [7] without thinking about investing in their future.

Disputes for natural resources will continue.

If in the last 70 years the wars in the world were led for crude oil, the list of reasons to begin a war will only get bigger in terms of natural resources. In the past, wars and conquering were mostly for gold, afterwards for oil, now will be for lithium, tungsten, beryllium. The global north will work on decarbonization and electric vehicles while the global south will die from pollution for the mines that serve the global north. One of the most eclatant examples for a global mining company that is registered as a mass polluter [8] in the sector, followed by endangering the environment of the autochthonous population around South America, Africa and Australia is the Canadian mining company Rio Tinto. This company is on the list of the lobbyists for the adoption of the legislation on critical raw materials.

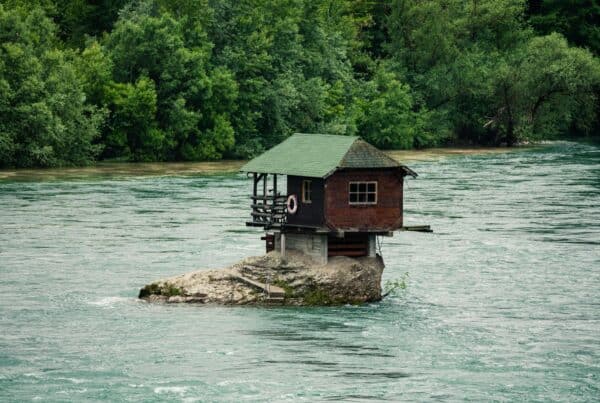

We will be somewhere in between depending on the question whether somebody is going to find lithium on the Macedonian territory. In Serbia, the Canadian company Rio Tinto continues to locate lithium deposits under the table and does not have any intention to implement standards for protection of the environment and all this is with an approval of the Serbian government. The Serbian government, under pressure from the public and environmental organizations, has only declaratively withdrawn from the project “Jadar” [9] in partnership with the Canadian company Rio Tinto [10] to open a lithium mine in western Serbia, close to the river Jadar. Nevertheless, Rio Tinto has continued to conduct research on other locations around Serbia in search for lithium deposits.

Macedonia can choose to remain as poor as it has been, or it can choose to become even poorer and more polluted by mining companies extracting rare raw materials. Sometimes it may not be a curse but a blessing not to have natural resources in order to avoid the interests of big corporations and thus to be used, drained, polluted and forgotten.

References:

- European Parliament News,“Critical raw materials: MEPs adopt plans to secure the EU’s supply and sovereignty”, December 12, 2023, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20231208IPR15763/critical-raw-materials-plans-to-secure-the-eu-s-supply ↑

- Ewa Rutkowska -Subocz, “Critical Raw Materials Act-what does it mean for business?”, Dentons, December 7, 2023, https://www.dentons.com/en/insights/alerts/2023/december/7/eu-critical-raw-materials-act what-does-it-mean-for-business E U Critical Raw MaterialsAct ↑

- Bruno Venditi, “The Critical Minerals to China, EU, and U.S. National Security”, November 30, 2023, Visual Capitalist, https://www.visualcapitalist.com/the-critical-minerals-to-china-eu-and-u-s-national-security/ ↑

- ibid ↑

- Ewa Rutkowska -Subocz, “Critical Raw Materials Act-what does it mean for business?”, Dentons, December 7, 2023, https://www.dentons.com/en/insights/alerts/2023/december/7/eu-critical-raw-materials-act what-does-it-mean-for-business E ↑

- Jeff McMahon, “Innovation Is Making Lithium-Ion Batteries Harder To Recycle”, July 1, 2018, Forbes, https://www.forbes.com/sites/jeffmcmahon/2018/07/01/innovation-is-making-lithium-ion-batteries-harder-to-recycle/?sh=43b86eb54e51 ↑

- Andreas Budiman, “EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act: Improved ambitions, but language still raises concerns for Environmental Standards, Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Protection, and Demand Reduction”, European Environmental Bureau News, December 12, 2023, https://eeb.org/eus-critical-raw-materials-act/ ↑

- Saul Jones, “After 150 years of damage to people and planet, Rio Tinto ‘must be held to account’ (commentary)”, April 5, 2023, Mongabay, https://news.mongabay.com/2023/04/after-150-years-of-damage-to-people-and-planet-rio-tinto-must-be-held-to-account-commentary/ ↑

- ibid ↑

- Leo Portal, “Serbia and Jadar: Will the project resume?”, June 15, 2023, Blue Europe, https://www.blue-europe.eu/analysis-en/country-analysis/serbia-and-jadar-lithium-mines-will-the-project-resume/ ↑