Jan Normann – University of Wrocław

Jan Normann is a third-year undergraduate student at the University of Wrocław, Poland, majoring in European Studies. Since March, he has interned at Blue Europe, serving as a Public Relations Intern. Jan is also a dedicated member of the Forum of Young Diplomats in Poland and contributes actively to the university’s academic society, Project Europe. He organizes significant events such as recent pre-election debates for the European Parliament. His international experience includes a year on the Erasmus+ exchange at Ben-Gurion University in Beer Sheva, Israel, and serving as an assistant to the Honorary Consul of Poland in Jerusalem, Zeev Baran. He participated in an international research team studying the impact of foreign powers on elections in European countries through social media platforms in 2023. Jan has also interned at the Polish Culture Institute in Paris and attended a week-long course focused on Ukraine in Covilhã, Portugal. His primary interest lies in diplomacy, particularly EU-Middle East relations.

1. An historical outline of Poland’s situation before joining the European Union.

Before joining the European Union, Poland went through a turbulent period of political and economic transition. The years 1952-1970 were characterized by antagonistic and conflictual relations with the European Communities, which the Polish authorities viewed as a “reactionary-bourgeois” creation that was the political and economic arm of NATO. Poland, as part of the Eastern Bloc, was strongly integrated with the Soviet Union and its satellite structures, which resulted in isolation from Western countries and prevented any serious talks on integration with Western Europe. The situation began to change in the 1970s, when Poland under Edward Gierek began a gradual warming of relations with the West, although full normalization of relations with Western Europe did not occur until after the political changes of the late 1980s[1].

The systemic transformation that began in Poland in 1989 was crucial for further steps toward EU membership. After the fall of communism, Poland intensively pursued integration with Western structures, seeing it as a guarantee of political and economic stability. In the 1990s, Poland consistently pursued an adjustment policy, undertaking a series of reforms aimed at meeting the criteria for EU membership. This process included the adoption of the “National Integration Strategy” and the “National Program of Preparation for EU Membership.” These steps were necessary to bring Polish law, economy and administration up to EU standards[2]. Diplomatic contacts and cooperation on many levels were also intensively developed, which eventually resulted in full EU membership on May 1, 2004.

Moreover, Poland also faced a number of internal challenges, including an economic transition that required a move from a centrally planned economy to a free market economy. This process was painful and required the restructuring of many industrial sectors, the privatization of state-owned enterprises and the reform of the financial system. However, these reforms were necessary for Poland to compete in the single European market. In addition, Poland had to adapt its legislation to the “acquis communautaire”, a body of EU law that covered a wide range of areas, from environmental protection to consumer rights. These reform and adjustment efforts were key to ensuring that Poland could not only join the EU, but also function effectively within its structures from day one of membership.

One of the key events on the road to European integration was the signing of the Europe Agreement in 1991, which established an association between Poland and the European Community. The treaty opened the way to trade liberalization and economic rapprochement with the western European countries. Poland, seeking to strengthen its position in the integration process, introduced numerous economic and political reforms that included market liberalization, privatization of state-owned enterprises and reform of the legal system. The introduction of local government reform, which aimed to decentralize power and strengthen local structures, was also a significant step. In 1994, Poland formally applied for membership in the European Union, which initiated an intensive negotiation process that lasted almost a decade.

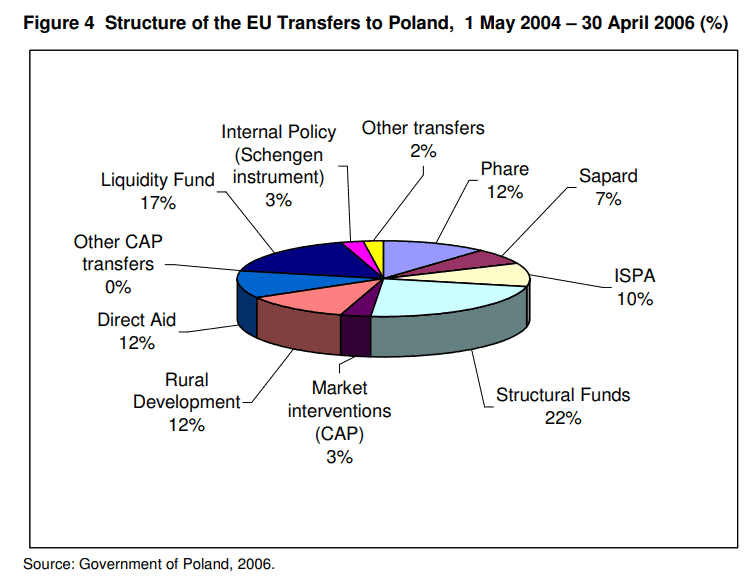

The pre-accession period was also a time of intensified cooperation with EU countries in various fields. Poland participated in pre-accession programs such as PHARE, ISPA and SAPARD, whose purpose was to support adjustment and modernization processes[3]. These financial programs enabled the implementation of many infrastructural, environmental and agricultural investments, which contributed to improving the quality of life in Poland and increasing the competitiveness of the economy. In the years leading up to accession, Poland also conducted an intensive information campaign aimed at familiarizing the public with the benefits of EU membership and preparing citizens to function in the new, integrated European environment.

2. Poland’s economic transformation in the ’90s.

Poland underwent a significant economic transformation in the 1990s, which began after the fall of communism in 1989. Between 1993 and 1995, Poland’s economy showed the highest growth rate among countries in Central and Eastern Europe that underwent similar political transformations. Gross domestic product (GDP) grew by 3.8%, 5.0% and 6.5%, respectively, in those years. The high dynamism of the economy was mainly due to rapid growth in exports and investment. Export growth was impressive – in the first eight months of 1995, export receipts totaled $14,736 million, an increase of 37.6% over the same period of the previous year. In addition, there has also been significant growth in investment, which in June 1995 was 48.3% higher than in June 1994[4].

Poland’s economic transformation, however, has not been without its challenges and problems. One of the main threats to the continuation of rapid economic growth was a reduction in the competitiveness of the Polish economy and an increase in production costs and domestic prices. Despite rapid growth, the Polish economy faced institutional barriers to development, such as the lack of a new constitution that could create a stable framework for continued economic momentum. Also problematic were issues related to the high budget deficit and the cost of servicing the public debt, which significantly limited the country’s ability to finance the investment and infrastructure necessary for long-term economic development. In turn, the rapid increase in foreign exchange reserves, despite its positive impact on the economy, did not translate directly into a significant decline in inflation, which continued to pose a serious challenge[5].

Poland’s economic transformation in the 1990s culminated in the introduction of a number of key reforms aimed at creating a stable market economy. Although Poland achieved significant economic growth rates, such as GDP growth of 3.8%, 5.0% and 6.5%, respectively, between 1993 and 1995, the process faced many challenges. Institutional barriers, such as the lack of a new constitution and the strong position of the non-market sector, hindered the full implementation of market economy principles. Despite high inflation and a budget deficit, Poland managed to accumulate significant foreign exchange reserves, which reached $12 billion in September 1995[6].

At the end of the 1990s, the economic transition brought some successes, such as an increase in exports and investment, but many problems remained unsolved. The weakening competitiveness of the Polish economy, too slow a decline in inflation and insufficient willingness to invest posed serious threats to further economic growth. Maintaining the pace of economic growth required a more consistent transformation policy focused on full implementation of market economy principles and macroeconomic stabilization. As a result, although Poland made significant progress, the economic transformation was not a uniform and smooth process, requiring further reforms and adjustments.

Source: Note on Poland’s political and economic situation and its relations with the European Union with a view to accession: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/enlargement/briefings/12a3_en.html.

3. The condition of the Polish economy at its entry into the European Union

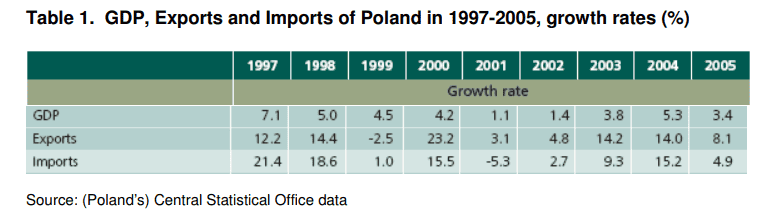

During Poland’s entry into the European Union in May 2004, the condition of the Polish economy was marked by a mix of challenges and optimistic growth forecasts. Before joining the EU, Poland had undergone a significant economic transformation, driven by trade and investment liberalization, as well as structural reforms. Between 1997 and 2005, the GDP growth rate averaged about 3.9% per year, indicating stable economic development. In the first years of EU membership, Poland maintained a solid economic growth rate, averaging 4.2% per year in 2004-2005, positioning itself as a fast-growing economy in the EU[7].

However, despite this positive growth trajectory, Poland faced several economic obstacles. The country struggled with a high unemployment rate, which was around 20% at the time of accession, reflecting serious structural problems in the labour market[8]. As a result, many people were living on a lower standard of living. In addition, Poland’s GDP per capita was only about 40.1% of the EU-15 average in 1997, underscoring the economic disparities that needed to be addressed. Despite these challenges, Poland’s integration into the EU brought significant benefits, including access to structural funds that helped finance key infrastructure projects and fostered economic convergence with Western Europe. EU membership has also stimulated foreign direct investment, further enhancing Poland’s economic development and integration into the single market.

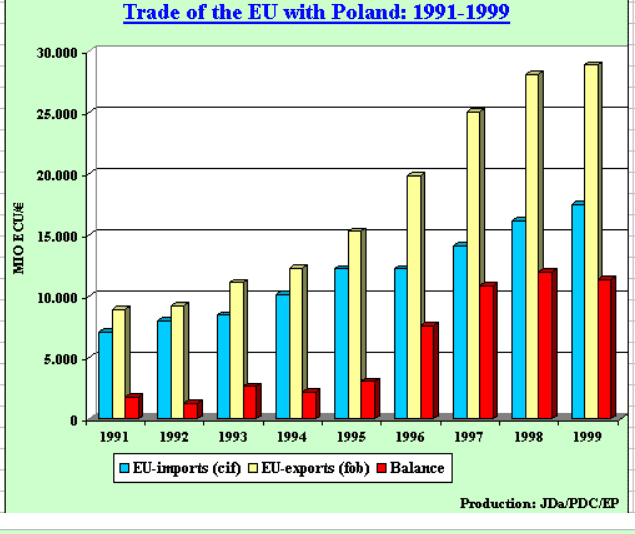

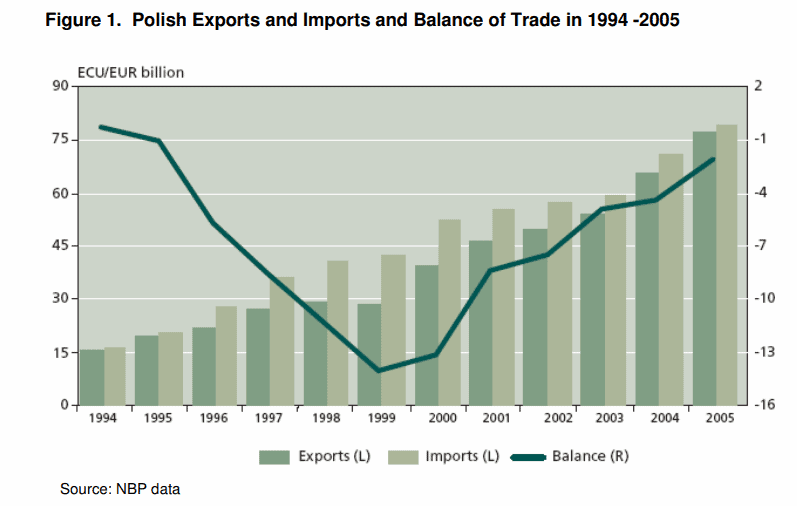

Another important factor was trade, the indicator of which has had a long evolution from the time of transition to the time of entry into the European Union. Poland’s path to membership began long before its official accession in 2004. It all started with the Europe Agreement in 1991, which laid the foundation for free trade with the EU. By 1993, the treaty had already abolished many tariffs, allowing Polish goods to move more freely into EU markets. This early start helped Polish exports and imports grow significantly even before official EU accession[9].

In the years leading up to EU membership, Poland’s trade with EU countries grew rapidly. By 2003, just before EU accession, exports of goods and services accounted for 33.4% of Polish GDP, up from 21.6% in 1994. Similarly, imports rose to 35.9% of GDP from 19.7%. This growth showed how much more open and integrated with the EU the Polish economy had become. Between 1999 and 2003, exports to EU member states rose from 13.2% to 20.1% of GDP[10].

Despite initial fears that EU accession might hurt the Polish economy by increasing imports, the opposite happened. Exports grew even faster than imports. By 2005, Polish exports had increased fivefold from 1994 levels, reaching €77.6 billion. This strong growth helped reduce the country’s trade deficit, which had been shrinking for six years in a row until 2005. Poland even began to have a positive trade balance with the EU, meaning that it exported more to the EU than it imported, while the remaining deficit was mainly with non-EU countries[11].

Joining the EU also meant that Poland adopted EU customs regulations that lowered tariffs on non-EU goods. The change boosted imports from developing countries, and also led to a record increase in exports to places like Russia and Ukraine. Polish farmers initially feared that EU membership would flood their market with imported food, but instead it led to an increase in Polish food exports to the EU[12].

An important aspect is the status of the funds that Poland has obtained from the EU. In 2004 Poland contributed 1.4% to the EU budget, but received 3.1% of EU budget expenditures, placing it as a net beneficiary with net transfers of €1.7 billion, equivalent to 0.75% of gross national income (GNI). Projections predicted a significant increase in EU funds in the following years, with expectations of reaching 1.2% of GDP in 2006, 1.5% in 2007 and 3.25% in 2008[13].

During the first 24 months of EU membership (May 2004 to April 2006), Poland received €7.5 billion from the EU budget, while paying in €4.6 billion, resulting in a positive net transfer of €2.8 billion. Pre-accession aid programs such as Phare, ISPA and SAPARD accounted for 28.4% of these payments, with funds for agriculture and rural development accounting for the largest share (26.9%). Despite the availability of these funds, Poland encountered serious challenges in using them effectively. Initially, the pace of absorption was slow due to the decentralized management system, suboptimal quality of legislation, insufficient public funds for co-financing projects, and an underdeveloped public administration system. By the end of 2005, only 50.7% of allocated funds had been contracted, and only 4.35% had been disbursed. However, 2006 saw improvements, including relaxation of regulations and increased administrative capacity, which facilitated better use of EU funds[14].

Describing Poland 20 years after joining the European Union, it’s hard to point out all the areas in which there has been a change, because the country looks completely different. From the appearance of ordinary streets and highways to huge investments and infrastructure. When describing the state of the Polish economy, it is necessary to point out several factors. First of all, after deducting EU contributions, Poland received more than 163 billion euros, or about 700 billion zlotys[15]. Moreover, from 2003 to 2022, Poland’s cumulative GDP more than doubled (by 109%). Meanwhile, nominal GDP increased from 206 billion euros to 751 billion euros, and GDP per capita from 5,400 euros in 2004 to 19,920 euros in 2023. There has also been an almost sixfold increase in merchandise exports from €60 billion to €350 billion. There has also been an almost sixfold increase in merchandise exports, from 60 billion euros to 350 billion euros. Unemployment in Poland is one of the lowest in the EU. Over the years it has fallen from 19% to 3%. The income gap between Poland and Western Europe is steadily narrowing. In terms of GDP per capita at purchasing power parity in 2022. Poland has overtaken Greece and Portugal. Membership in the European Union also means greater confidence on the part of foreign investors. By the end of 2022, the total value of foreign direct investment in Poland amounted to 251.6 billion euros, 86% of which went to EU countries. In 1993-2003, the average annual inflow of foreign direct investment was €4 billion. Between 2004 and 2022, the value nearly quadrupled to 15 billion euros. Among other things, foreign direct investment has contributed to the growth of employment, labor productivity and Poland’s foreign trade[16].

4. Labor market as an example of the country’s economic resilience.

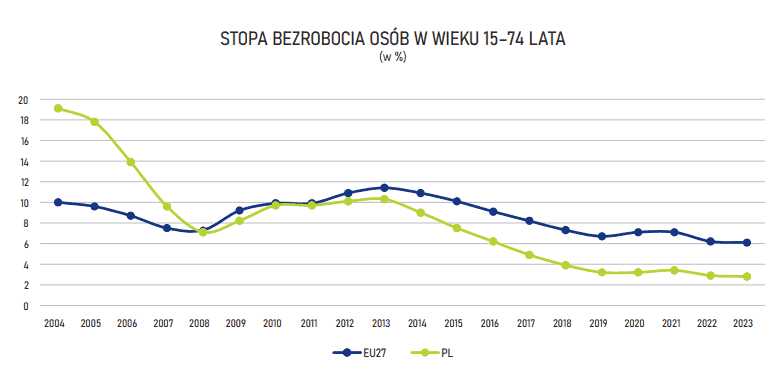

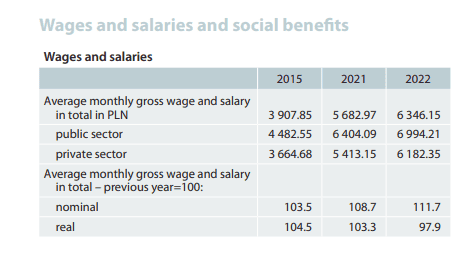

Undoubtedly, one of Poland’s greatest successes in the EU is progress in the dimension of the labor market. Over the course of twenty years in the European Union, the labor market has undergone substantial transformations. According to data from the Central Statistical Office, unemployment in Poland was a staggering 19.5% in May 2004. Today, recent statistics from March show that it has plummeted to 5.3%. Eurostat reports an even more optimistic picture, with unemployment at 2.8% at the end of 2023, and slightly rising to 2.9% in March 2024. This ranks as the second-lowest unemployment rate across the entire European Union. Poland’s EU membership has also seen significant wage increases. In 2004, the average gross monthly salary was a mere PLN 2290. By 2023, this figure had surged to PLN 7155, marking a more than threefold increase over two decades[17].

The evolution of the decline in unemployment in Poland from 19% in 2004 to around 3% in early 2024 can be seen in the statistic below.

Source: 20 lat razem. Polska w Unii Europejskiej, Główny Urząd Statystyczny.

This is also important because the increase in the number of workers in the labor market is positively reflected in wages across the country, which are rising year after year.

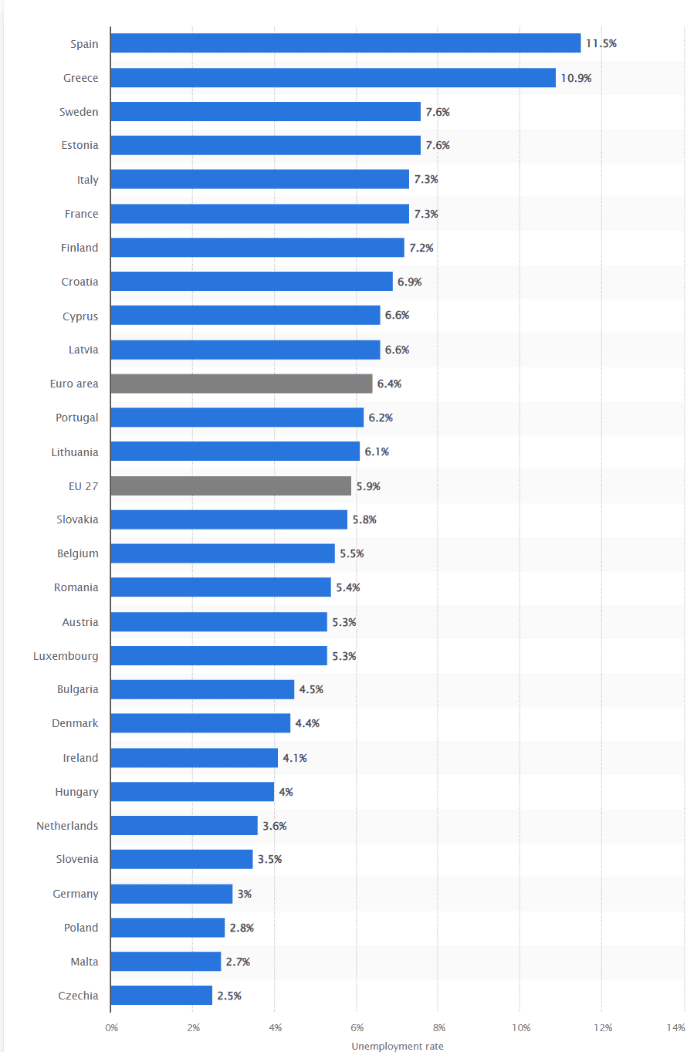

Polish success is evident when comparing statistics with other European Union countries. According to Eurostat, the unemployment rate in March 2024 was 2.9 percent, and Poland ranked – along with the Czech Republic – first among European Union countries with the lowest unemployment rate. By comparison, the EU average was 6 percent, and in the Eurozone it was 6.5 percent[18].

This trend has been observable for many years, and the following statistic from August 2023 is a good example:

Source: Statista.

In conclusion, Eurostat’s April data confirms that the Polish labour market is still in good shape compared to other countries in the Community. The persistently very low unemployment rate testifies to strong demand for workers and limited labour resources.

5. An assessment of Poland after 20 years in the EU: Progress and current challenges in the economic dimension.

Poland’s membership in the European Union has had a very significant impact on the amount of economic growth. Depending on the method and data used, various studies indicate that membership in the European Union is responsible for one-third to one-half of Poland’s economic growth between 2004 and 2023. Contributing factors include access to the EU single market, foreign investment attracted to Poland by its presence in the Union, and billions of euros in European funds. Between 2004 and 2023, Poland’s GDP per capita rose from 50% of the EU average to 80% of the average. The rate of economic growth was the third highest in the European Union, after Ireland and Malta[19].

Below are two charts. On the left is shown the increase in Poland’s share of the European Union’s GDP. On the right is a list of Poland’s GDP growth over the years.

Source: 20 lat razem. Polska w Unii Europejskiej, Główny Urząd Statystyczny.

Moreover, over the past 20 years, the value of exports from Poland to other EU countries has increased almost sixfold – from €45 billion in 2004 to €262 billion in 2023. With access to a free, duty-free market, Poland has become one of the leading suppliers of many essential products, such as cosmetics, furniture, batteries and car parts. Polish agriculture can also boast a high level of export growth. In 2002, two years before joining the European Union, we imported more food than we exported. In more than 20 years, the situation has changed significantly – in 2022 Poland exported agri-food products with a total value of 47.6 billion euros, with most going to the European Union. That’s nine times more than in 2004[20].

It is worth adding that new jobs have been created for thousands of Poles, 5 million jobs are functioning in Poland thanks to the export of goods and services to the rest of the European Union. Additional jobs are also created by European funds. 325,000 jobs have been created directly thanks to them, 165,000 indirectly, and another 100,000 thanks to the increase in demand resulting from the use of EU funds – in total, this has allowed some 590,000 Polish women and men to find work. For example, the largest private employer in Poland employs about 80 thousand workers[21].

Since Poland joined the European Union, EU funds have played a key role in the country’s economic development. Until 2024, Poland has received around PLN 55.2 billion for various projects supporting entrepreneurs, local governments and innovative initiatives. Programs such as the Intelligent Development (IE OP) and Eastern Poland (EOP) have enabled the development of innovative solutions, which has increased the competitiveness of Polish companies in international markets[22].

In 2024, PARP (eng. Polish Agency for Enterprise Development) is involved in the implementation of cohesion policy support instruments for 2021-2027 under three national programs: European Funds for a Modern Economy (FENG) (PARP budget: €2.82 billion); European Funds for Social Development (FERS) (PARP budget: PLN 1.37 billion); and European Funds for Eastern Poland (FEPW) (PARP budget: €1.39 billion). In addition, the Agency will also offer investment funds from the National Recovery and Resilience Plan – a comprehensive reform program in response to the pandemic crisis. As part of the implementation of the 2021-2027 programs, 24 calls for proposals are planned to be announced this year for a funding amount of nearly PLN 4.80 billion[23].

Poland’s economy faced significant challenges in 2023, with real GDP growth decelerating sharply to 0.2% from 5.3% in 2022. High inflation, tighter financing conditions, and reduced household support measures curtailed private consumption despite robust labor market conditions and wage increases. Exports also slowed due to weakened demand from major trade partners. However, investments, bolstered by firms’ strong financial performance and the electoral cycle, provided some economic support. Inflation peaked at 18.4% year on year in February 2023 but eased to 3.9% year on year by January 2024, aided by falling commodity prices, a stronger zloty, and supply chain improvements[24].

Looking ahead, Poland’s economic growth is projected to rebound to 3% in 2024 and 3.4% in 2025, driven by rising private consumption due to declining inflation, wage growth, and increased family transfers. Structural reforms and EU funds are expected to further boost investments. However, inflationary pressures may resurface in the latter half of 2024 due to the reinstatement of VAT on basic foodstuffs and phasing out of energy price caps. The fiscal deficit is projected to remain high at 5% of GDP in 2024, influenced by tax reforms, increased defense, and election-related spending. Poverty rates are expected to decline, although vulnerable households remain at risk due to the long-term reductions in minimum income program coverage[25].

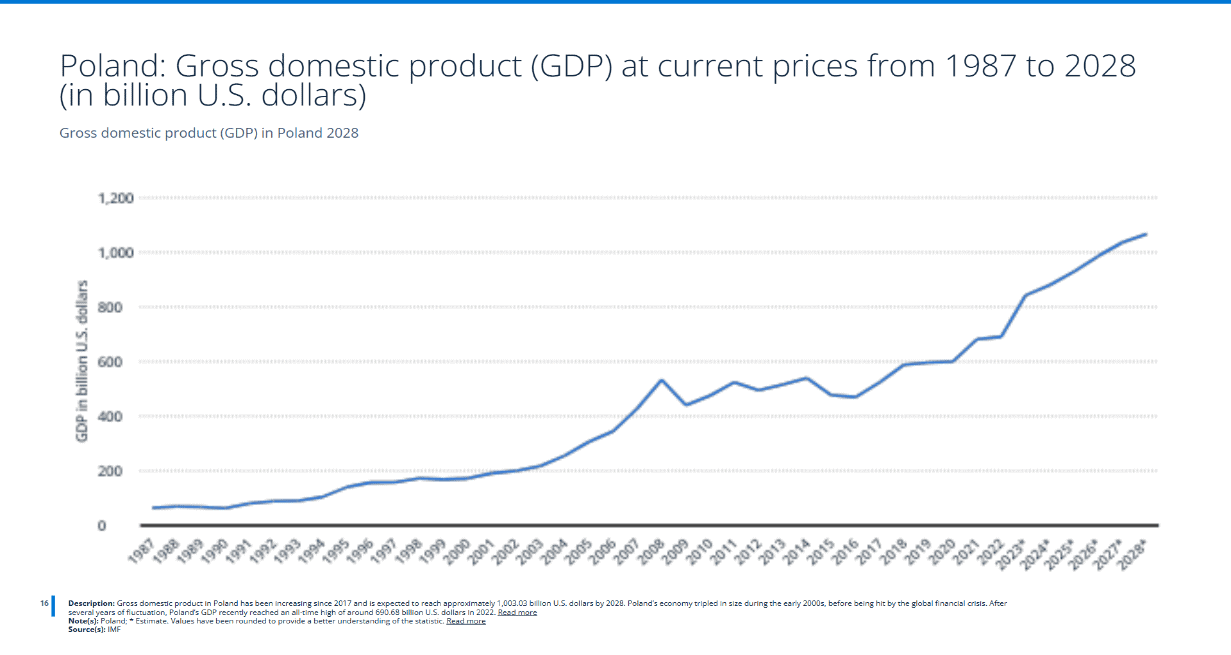

On the chart below, the projected GDP growth of Poland until 2028 can be observed.

Source: Statista.

6. Conclusion

Since joining the European Union in 2004. Poland has undergone a significant economic transformation. Over the past two decades, the country has achieved significant successes, including a doubling of GDP, a sixfold increase in exports and a drop in unemployment from 19% to just 3% in 2024. EU membership has provided Poland with access to significant structural funds that have supported infrastructure development, innovation and modernization of various sectors of the economy. EU funds, such as the Intelligent Development and Eastern Poland programs, have allowed the development of modern solutions and increased the competitiveness of Polish companies in international markets. In addition, the inflow of foreign investment has increased significantly, which has contributed to an increase in employment and productivity.

Despite these successes, Poland still faces many challenges. Poland’s economy slowed in 2023, with GDP growth of just 0.2%, compared to 5.3% in 2022. High inflation, tighter financial conditions and reduced support for households have negatively affected private consumption. In addition, Russia’s aggression against Ukraine has introduced geopolitical uncertainty, which has affected the economic situation in the region, especially in terms of exports and external demand. In the coming years, Poland is expected to need to continue structural reforms and make effective use of EU funds to maintain stable economic growth and increase resilience to external risks.

According to a personal opinion, I, as a person born and raised in the EU era, can only point out what benefits come from living here. As a student, the Erasmus program has given me incredible personal and academic growth, meeting people from all over Europe with whom I am still friends to this day. In addition, the state of the country itself, the buildings, the quality of life is every year more and more similar to the main countries of Western Europe. Therefore, assessing the 20 years of Poland in the European Union, it should be pointed out that this is the best period in the entire history of this country.

Resources

- Willa, R. (2007), Droga do członkostwa w Unii Europejskiej–przykład Polski, Dialogi polityczne, no 8, p. 84-85. ↑

- Ibidem, p. 93. ↑

- Ibidem. ↑

- Wilczyński, W. (1996). Wzrost gospodarczy a transformacja ustrojowa: Polska pod koniec lat 90-tych XX wieku, Ruch Prawniczy, Ekonomiczny i Socjologiczny, (1), 71-84. ↑

- Ibidem. ↑

- Ibidem. ↑

- Balcerowicz, E. (2007). The Impact of Poland’s EU Accession on its Economy, Center for Social and Economic Research CASE report, p. 14-15. ↑

- Statistics Poland, Unemployment rate 1994-2024, https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/labour-market/registered-unemployment/unemployment-rate-1990-2024,3,1.html. ↑

- Chruściel, M., & Kloc, K. (2013). Polska w Unii Europejskiej–proces akcesyjny i priorytety polskiej polityki w ramach UE, Stosunki Międzynarodowe i Polityka. ↑

- Balcerowicz, E. (2007). The Impact of Poland’s EU Accession on its Economy. Center for Social and Economic Research CASE report, p. 18-19. ↑

- Ibidem, p. 19. ↑

- Ibidem. ↑

- Ibidem, p. 24-26. ↑

- Ibidem. ↑

- Dobrze, że jesteśmy razem – 20 lat Polski w Unii Europejskiej, https://www.gov.pl/web/premier/dobrze-ze-jestesmy-razem. ↑

- Ibidem. ↑

- A. Baranowska-Skimina, Jak minęło 20 lat Polski w Unii Europejskiej?, eGospodarka.pl, https://www.egospodarka.pl/187424,Jak-minelo-20-lat-Polski-w-Unii-Europejskiej,1,39,1.html. ↑

- GUS potwierdził nasze szacunki. Bezrobocie w kwietniu 2024 najniższe od 30 lat, https://www.gov.pl/web/rodzina/gus-potwierdzil-nasze-szacunki-bezrobocie-w-kwietniu-2024-najnizsze-od-30-lat. ↑

- Skąd jest nasz wzrost gospodarczy?, https://polskawunii.pl/wzrost-gospodarczy. ↑

- Ile mamy z eksportu do UE?, https://polskawunii.pl/eksport-do-unii. ↑

- Ile miejsc pracy dzięki UE?, https://polskawunii.pl/miejsca-pracy. ↑

- 20 lat Polski w UE. Fundusze Europejskie wspierają rozwój polskich firm, https://nto.pl/20-lat-polski-w-ue-fundusze-europejskie-wspieraja-rozwoj-polskich-firm/ar/c3-18534551. ↑

- Ibidem. ↑

- The World Bank in Poland, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/poland/overview#3. ↑

- Ibidem. ↑