Agriculture has been a pivotal sector in the economy and society, evolving over time from being the primary economic sector to a more diversified role. Originally, it was the only sector capable of generating the necessary economic surplus for further development, including industrialization.

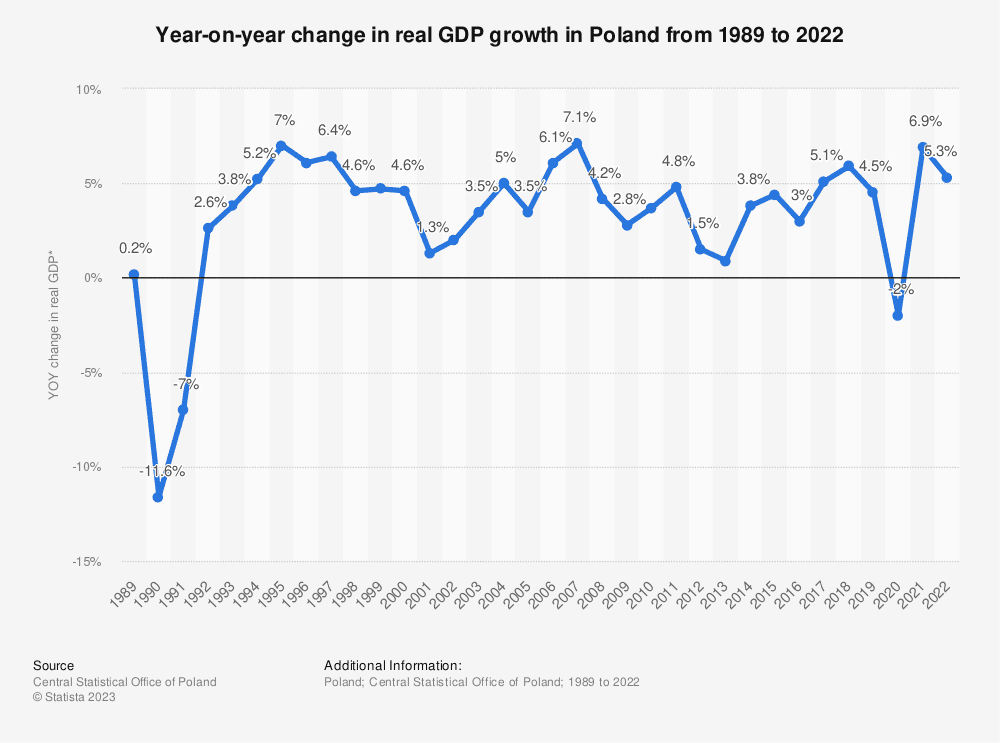

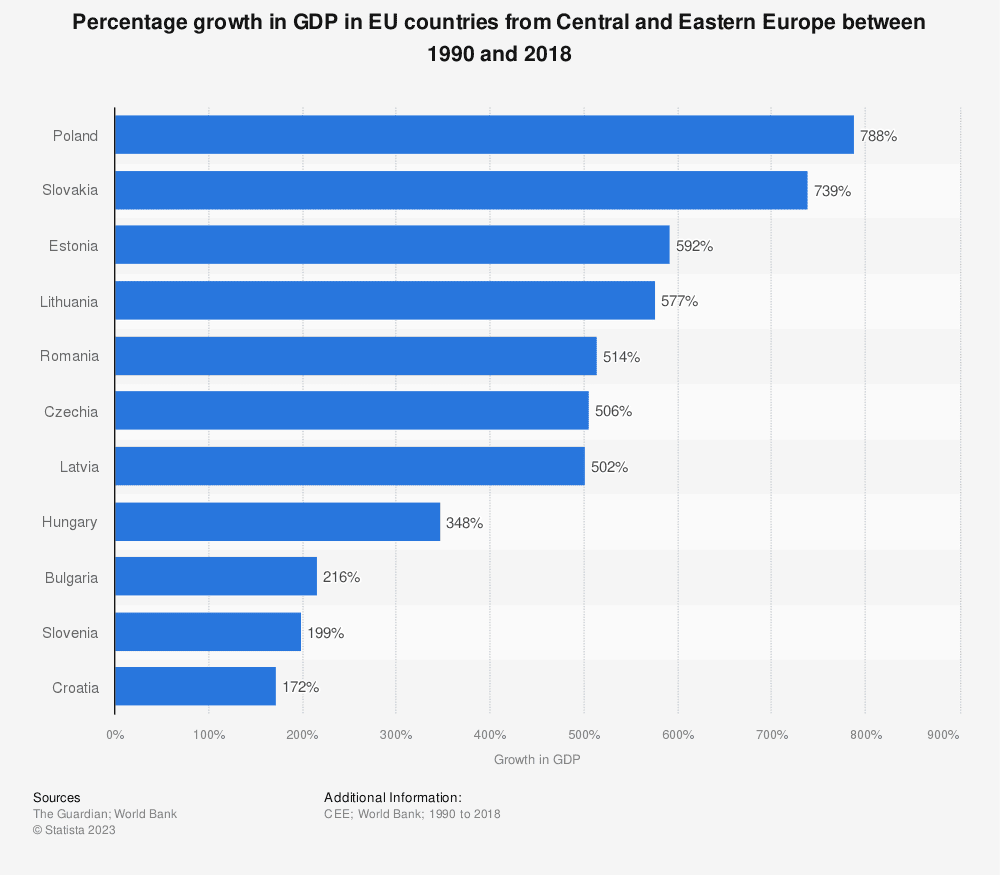

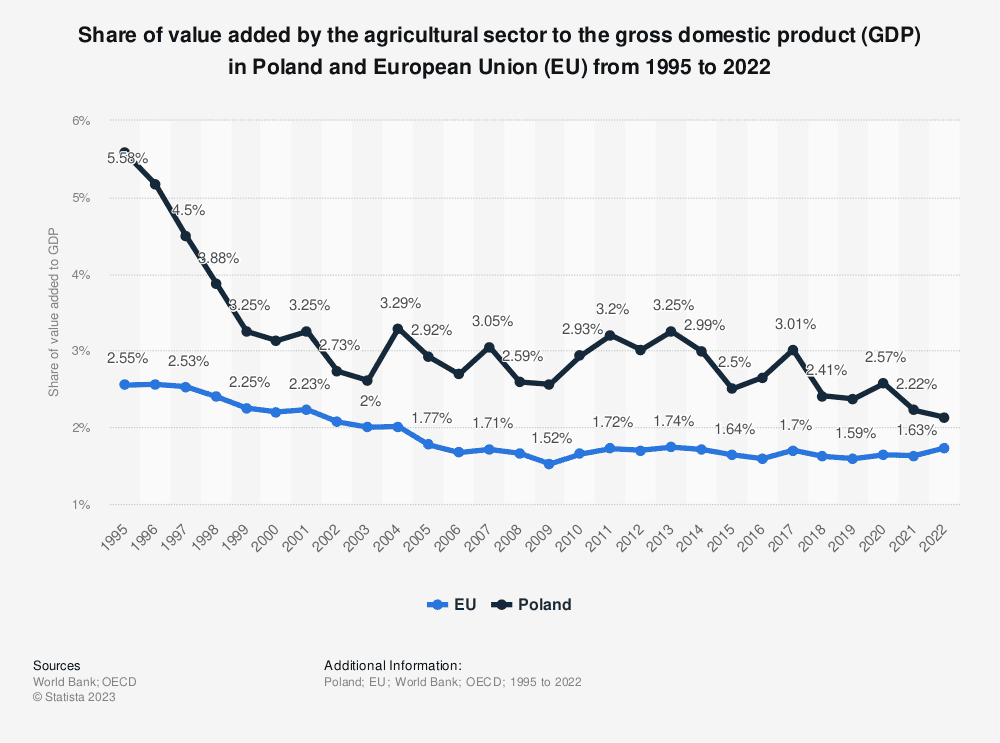

As economic growth progresses, agriculture’s relative importance in the economy, in terms of its share in potential, production, and income effects, has been decreasing. This trend began around 200 years and accelerated considerably in the post-WW2 economic boom. Despite this relative decline, agricultural production and subsequently food production have continuously grown. For instance, while the Polish GDP has been steadily growing since the dissolution of the USSR (Figure 1), totaling a 788% GDP growth from 1990 to 2018 (Figure 2); the share of value added by the Polish agricultural sector to the GDP has been declining from a 5.58% in 1995 to a 2.13% in 2022 (Figure 3).

The forces influencing agriculture’s evolution operate at global, national, and local levels. Globally, factors like international trade, agricultural productivity growth leading to falling food prices, and international regulations (WTO, OECD) are significant. Nationally, changes in GDP per capita, urbanization, agricultural policies, supply chain integration, and environmental constraints (like climate policy) play a crucial role. At the local level, demographic changes, health protection levels, agricultural property rights and guarantees, local agricultural infrastructure, and market access are key factors.[1]

Figure 1: Year-on-year change in real GDP growth in Poland from 1989 to 2022

Figure 2: Percentage growth in GDP in EU countries from Central and Eastern Europe between 1990 and 2018

Figure 3: Share of value added by the agricultural sector to the gross domestic product (GDP) in Poland and European Union (EU) from 1995 to 2022

A brief outlook of the agricultural sector in Poland

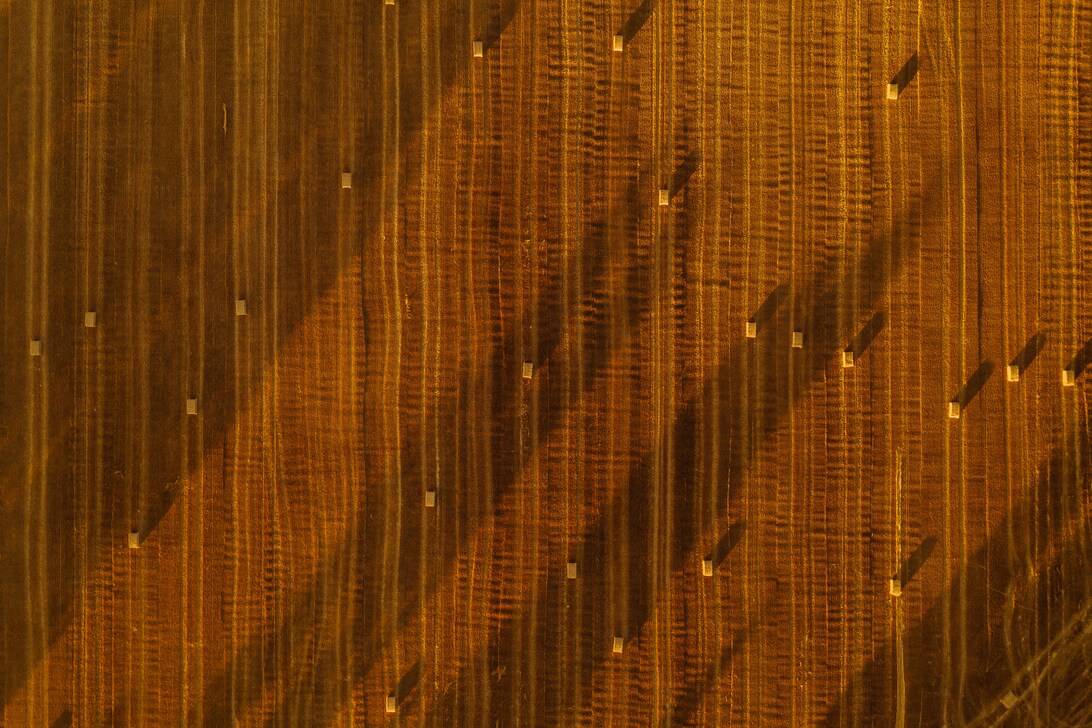

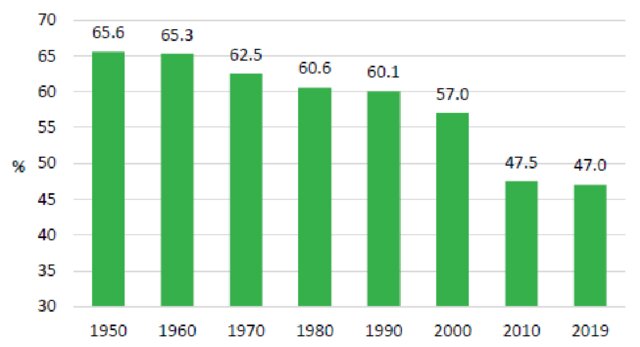

As shown in Figure 4 below, in the year 1950 agricultural holdings occupied 20,440 thousand hectares, constituting 65.6% of the total land area of Poland. However, by 2019, this figure had decreased to 14,690 thousand hectares (47.0 percent). On account of this, around 5,750 thousand hectares were rendered unusable. The contraction in territory for agriculture was mostly attributable to urbanization aspirations and the requirements of other economic sectors, such as the mining (mine regions) and communication industries.[2]

Figure 4. The share of agricultural land in Poland (period 1950-2019)

Source: Kowalczyk and Kwasek, 2020.[3]

Polish family farms continue to be fragmented, notwithstanding the implementation of several legal measures intended to mitigate this issue. The fragmentation is not observed in the context of other farms, including those owned by commercial and public entities, where the average agricultural land area typically surpasses 100 hectares.[4] Borzutzky and Kranidis[5] argue that the fundamental challenges faced by the agricultural industry, including overemployment, inadequate capital, and farm size, remain unresolved despite the EU’s entry. Notwithstanding this, membership in the European Union offers the possibility of a brighter future contingent on the establishment of a stable economic climate and the attraction of foreign capital. Small farm ownership functioned as a social security component, but nowadays the substantial number of farms fails to generate a sufficient standard of living. As a consequence, farm managers maintain a restricted level of involvement in agricultural operations.[6]

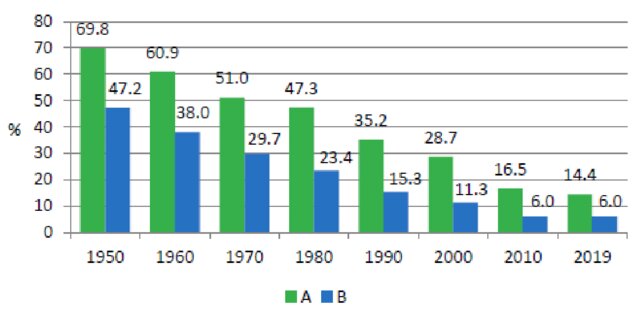

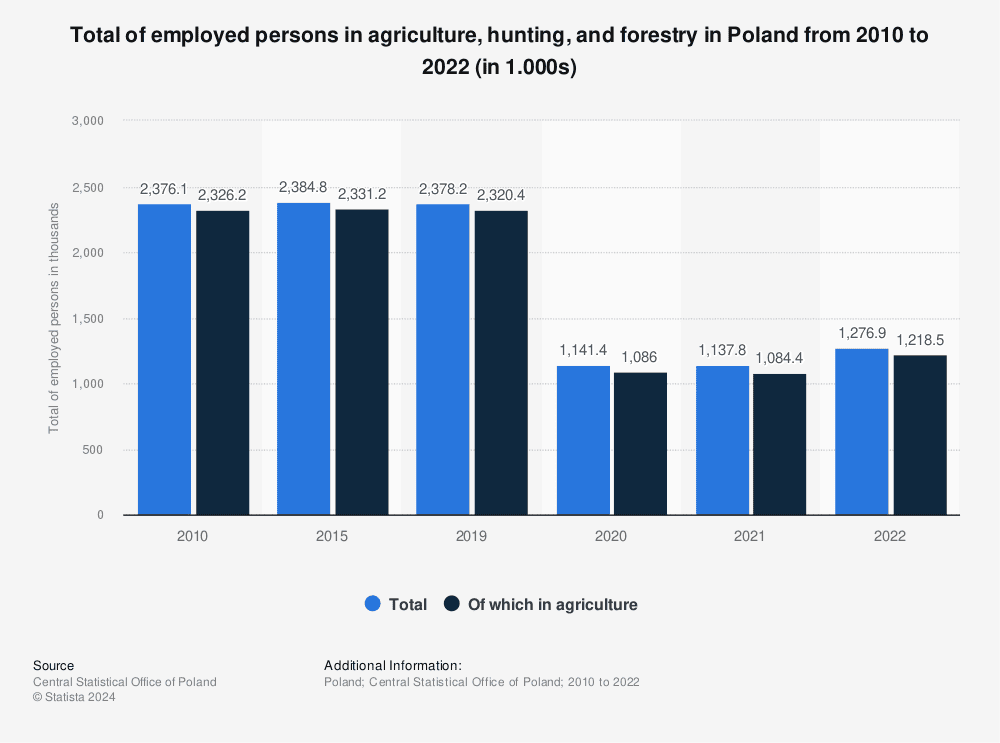

The share of people working in the agricultural sector in Poland has been constantly decreasing from 1950 as shown in Figure 5 blow, as per urbanization and industrial development processes: falling from 47.2 percent in 1950 to 6.0 percent in 2019. Thus, although in the immediate aftermath of World War II nearly one Pole out of two was employed in agriculture, only the sixteenth or seventeenth do so at now. The magnitude of the phenomena described in the literature as the “migration” contribution of agriculture to economic expansion is shown by these alterations. Figure 6 shows an accentuation of decrease in the total number of employed persons in agriculture due to Covid pandemic crisis. Particularly, due to the emergency it dropped more than half.

Figure 5. Share of people working in agriculture in the total number of employees (A) and the total population (B), (period 1950-2019).

Source: Kowalczyk and Kwasek, 2020.[7]

Figure 6. Total of employed persons in agriculture, hunting, and forestry in Poland from 2010 to 2022

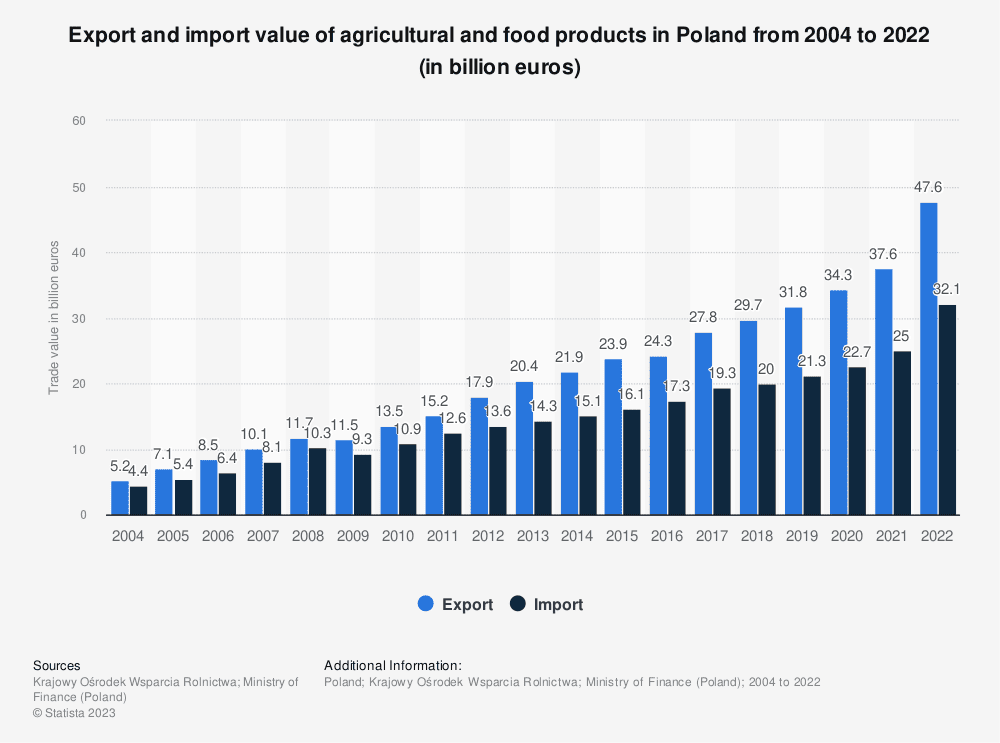

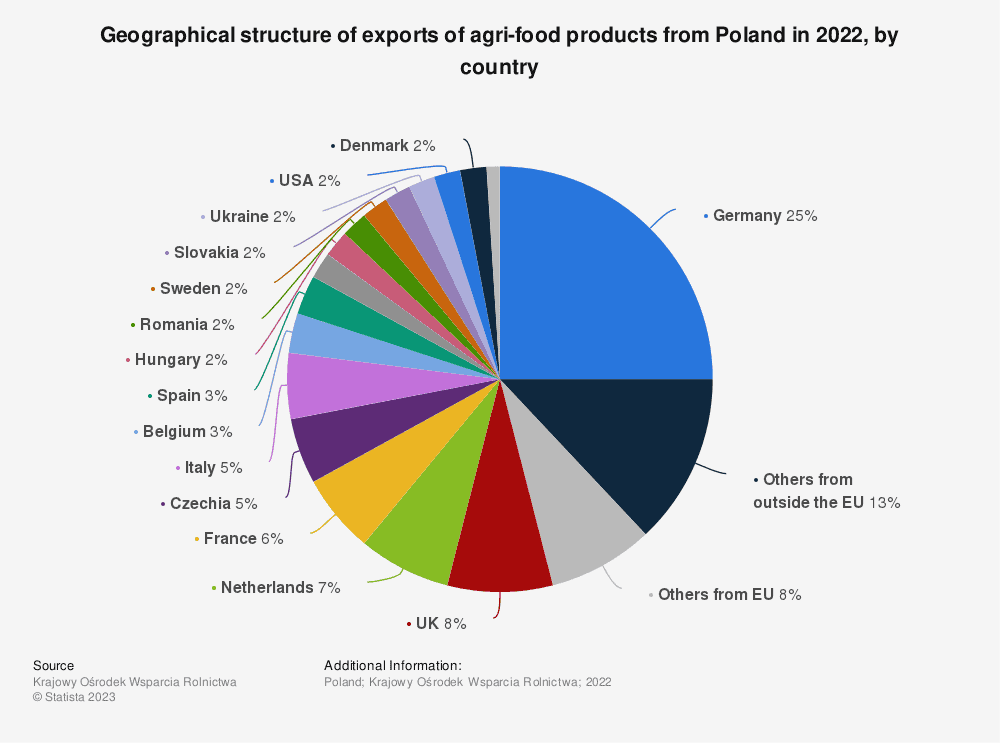

In terms of import and export of agricultural goods, Figure 7 below shows that while both importations and exportations have constantly grown – with exceptions for instance during the global financial crisis, export has been grown at a faster rate, positively widening the agricultural balance of trade. Additionally, as per Figure 8, the main trading partners of the agricultural sector of Poland reside in the EU, accounting for more than 85% of the total trade.

Figure 7. Export and import value of agricultural and food products in Poland from 2004 to 2022

Figure 8. Geographical structure of exports of agri-food products from Poland in 2022, by country

A glance at the future of the Agri sector in Poland

On April 15, 2023, Poland and Hungary announced bans on the import of grain and various other food items from Ukraine.[8] This decision was taken to safeguard the interests of local farmers in both countries, a move that initially contradicted EU common trade law. This move was taken as consequence of Ukraine’s shift to using European Union transit routes for its grain exports, as its traditional Black Sea pathways were obstructed due to Russia’s invasion. This change in logistics has led to an accumulation of grain in transit, resulting in a drop in prices and consequent protests from farmers. This situation also led to the resignation of Poland’s agriculture minister.

The new government in Warsaw has now successfully obtained a concession from the EU regarding the control of Ukrainian food exports.[9] The European Commission is now prepared to implement additional safeguards for countries bordering Ukraine. The implementation of these tighter safeguards represents a development in the policies of Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk, who has been attempting to harmonize domestic economic interests with a goal to reposition Poland in EU policymaking. This is occurring against the backdrop of the previous administration’s complex interactions with Brussels, especially in areas concerning Poland’s rule of law.

The recent developments in EU’s trade policy reflect a nuanced approach to balancing regional economic stability with the broader geopolitical context. The focus on country-specific safeguards indicates a shift towards more tailored responses to the unique challenges faced by individual member states. This approach could set a precedent for future trade policies, especially in situations where external factors like conflict significantly impact the traditional trade dynamics.

References

-

Peter Hazell and Stanley Wood, ‘Drivers of Change in Global Agriculture’, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 363, no. 1491 (26 July 2007): 495–515, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2007.2166. ↑

-

Stanisław Kowalczyk and Mariola Kwasek, ‘Agricultural Sector in Economy of Poland in 1950-2020.’, Western Balkan Journal of Agricultural Economics and Rural Development 2 (1 January 2020): 77–98, https://doi.org/10.5937/WBJAE2002077K. ↑

-

Kowalczyk and Kwasek. ↑

-

Paweł Bryła, ‘Agricultural Enterprises in Poland’, in Managing Agricultural Enterprises: Exploring Profitability and Best Practice in Central Europe (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018), 3–25, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-59891-8_1. ↑

-

Silvia Borzutzky and Emmanuel Kranidis, ‘A Struggle for Survival: The Polish Agricultural Sector from Communism to EU Accession’, East European Politics and Societies 19, no. 4 (1 November 2005): 614–54, https://doi.org/10.1177/0888325404270670. ↑

-

P. Chmieliński, ‘Economic Activity of Managers of Family Farms in Poland – a Spatial Perspective.’, International Scientific Conference: Sustainable Agriculture and Rural Development in Terms of the Republic of Serbia Strategic Goals Realization within the Danube Region, Regional Specificities, 10-11 December 2015, Belgrade, Serbia. Thematic Proceedings, 2015, 429–44. ↑

-

Kowalczyk and Kwasek, ‘Agricultural Sector in Economy of Poland in 1950-2020.’ ↑

-

Euractiv, ‘Poland, Hungary Ban Ukraine Grain to Protect Local Farms’, www.euractiv.com, 16 April 2023, https://www.euractiv.com/section/europe-s-east/news/poland-hungary-ban-ukraine-grain-to-protect-local-farms/. ↑

-

Raphael Minder et al., ‘Poland Secures EU Concession to Limit Food Exports from Ukraine’, Financial Times, 22 January 2024, sec. Poland, https://www.ft.com/content/3fcc5b32-cdd3-49a5-a0f4-5af80af7288f. ↑